You probably think of your bones as solid, dry, and static pieces of biological "wood" holding you up. You're wrong. When you look at a compact bone cross section under a microscope, it doesn't look like a solid wall at all. It looks like a dense, thriving forest of concentric circles, teeming with life and constant construction.

Bones are alive. They’re wet. They’re incredibly busy.

If you’ve ever wondered why a fracture takes weeks to heal or why your skeleton doesn't just snap like a twig when you jump, the answer is hidden in that cross-sectional view. It’s all about the architecture. Cortical bone, which is the technical name for this compact stuff, makes up about 80% of your skeletal mass. It's the "shell" that protects the spongy interior. But it isn't just a shell; it’s a high-tech engineering marvel that manages weight distribution and mineral storage with insane precision.

What You’re Actually Seeing in a Compact Bone Cross Section

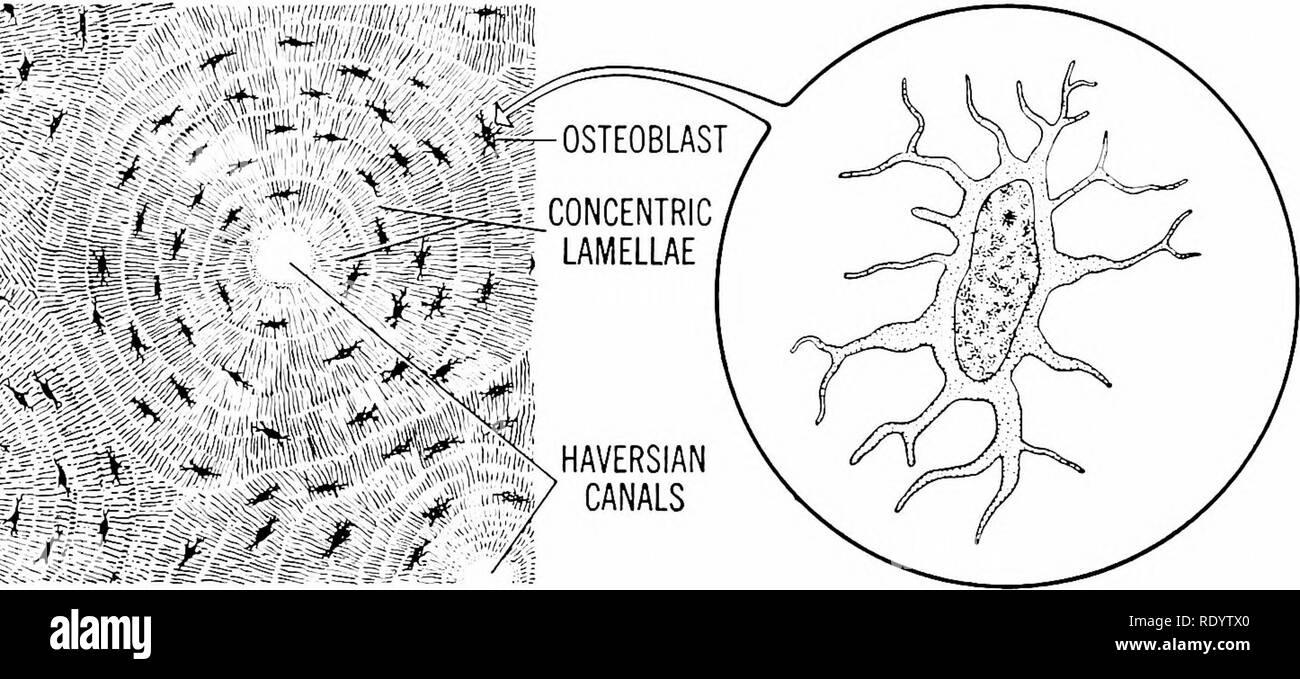

Look at a slide of a ground bone section. Honestly, it looks like a bunch of sliced tree trunks packed tightly together. These "tree trunks" are called osteons, or Haversian systems. This is the fundamental unit of compact bone. If you don't understand the osteon, you don't understand how humans move.

Each osteon is a cylinder. In the center of that cylinder is a hole called the Haversian canal.

Think of this canal as the main highway. It carries blood vessels and nerve fibers. This is why it hurts so much when you break a bone; those nerves are right there in the thick of it. Around that central highway, the bone is laid down in concentric rings called lamellae. The orientation of collagen fibers in these lamellae shifts with every layer. One layer might run clockwise, the next counter-clockwise. This crisscross pattern is what keeps your femur from shattering when you're running a marathon or just tripping over the curb.

Between these rings, you'll see tiny dark spots. Those are lacunae.

💡 You might also like: Do You Get Vitamin D From a Tanning Bed? Here is What the Science Actually Says

Inside those little caves live the osteocytes. These are the "managers" of your bone. They are actually former bone-building cells (osteoblasts) that got trapped in their own construction work. But they don't just sit there. They have long, hair-like extensions that reach out through tiny tunnels called canaliculi. This allows them to "talk" to each other and sense mechanical stress. If you start lifting weights, the osteocytes feel that pressure and send signals to build more bone. It's a real-time feedback loop happening inside your legs right now.

The Plumbing System: Beyond the Vertical Canals

People often assume the blood just stays in those vertical Haversian canals. It doesn't. Your bone needs a way to get nutrients from the outside surface (the periosteum) all the way into the marrow.

This happens through Volkmann’s canals (or perforating canals).

These run horizontally. They intersect the vertical Haversian canals, creating a grid-like plumbing system. This ensures that even the cells buried deep within the densest part of your compact bone get oxygen and calcium. Without this horizontal network, the inner parts of the compact bone cross section would literally starve and die.

💡 You might also like: Pull out method chances of getting pregnant: Why "almost" isn't enough

The Composition of the Matrix

It's not just "calcium." The bone matrix is a composite material. You have the organic part—mostly Type I collagen—which provides flexibility. Then you have the inorganic part—hydroxyapatite crystals (calcium phosphate).

If you took away the collagen, your bones would be as brittle as glass. If you took away the minerals, your bones would be as flexible as rubber bands. You need both. In conditions like osteogenesis imperfecta, the collagen is messed up, leading to frequent breaks. In rickets, the mineral side is the problem. A healthy cross-section shows a perfect, stony balance between the two.

Why the "Interstitial" Space Matters

When you look closely at the gaps between the circular osteons, you'll see irregular fragments of bone that don't look like perfect circles. These are interstitial lamellae.

👉 See also: Enfermedad de las encías: lo que tu dentista en España probablemente no te explica con claridad

They are the "ghosts" of old osteons.

Your bone is constantly being remodeled. Cells called osteoclasts (the "demolition crew") move through and eat away old, damaged bone, leaving a tunnel. Then, osteoblasts come in and fill it back up with new layers. The interstitial lamellae are just the leftovers of previous generations of bone. This is why an older person's bone looks much more "cluttered" under a microscope than a teenager's. It's a record of every repair job your body has ever done.

Practical Insights for Bone Health

Understanding the compact bone cross section isn't just for anatomy students. It tells you exactly how to take care of yourself.

- Impact is non-negotiable. Osteocytes only signal for more bone density when they feel mechanical "loading." This is why swimming, while great for the heart, does almost nothing for bone density. You need weight-bearing exercise—walking, running, or lifting—to trigger the remodeling process within the osteons.

- Nutrition is about more than just milk. While calcium is the "bricks" of the hydroxyapatite, you need Vitamin D to actually get that calcium into the blood, and Vitamin K2 to ensure it ends up in the bone and not your arteries.

- Healing takes time because of the plumbing. When a bone breaks, the entire Haversian system is disrupted. The body has to rebuild those blood vessels and then lay down "callus" bone (which is messy and unorganized) before it can eventually remodel it back into the neat, concentric circles of compact bone.

Microscopic health is macroscopic health. The next time you feel the weight of your own body, remember the thousands of tiny "tree trunks" in your legs, working in tandem, pulsing with blood, and constantly rebuilding themselves to keep you standing.

To maintain these structures as you age, focus on high-protein intake to support the collagen matrix and consistent resistance training to keep those osteocytes "awake" and active. Chronic inflammation and high cortisol can actually speed up the "demolition crew" (osteoclasts) while slowing down the "builders," leading to the thinning of these compact layers—a process we know as osteoporosis. Keep the builders busy.