C.S. Lewis didn't start with a moral. He didn't even start with a plot. He started with a single image that stayed stuck in his head since he was sixteen: a faun carrying an umbrella and parcels in a snowy wood. That’s it. That’s how The Chronicles of Narnia began. It wasn't some grand corporate strategy or a planned seven-book epic. It was just a mental picture that eventually grew into one of the most influential pieces of literature in the 20th century. Honestly, it’s kind of wild when you think about how many people grew up thinking a wardrobe was a potential portal to another dimension because of a guy who just liked the idea of a goat-man in the snow.

Most people think they know Narnia. You’ve probably seen the Disney movies or had the books read to you as a kid. But the actual history behind the series—and the weird, messy way it was written—is way more interesting than the "Sunday school" version most people talk about. Lewis was a scholar at Oxford. He was a veteran of the Great War. He was a guy who loved old Norse myths and medieval cosmology. When he sat down to write The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, he wasn't trying to write a "children’s book" in the way we think of them today. He was trying to write the kind of book he actually wanted to read.

What Most People Get Wrong About Narnia

There is this massive misconception that The Chronicles of Narnia is just a strict Christian allegory. People say Aslan is Jesus. But Lewis actually hated that word—allegory. He called it a "supposal." His logic was: "Suppose there was a world like Narnia, and the Son of God became a Lion there as He became a Man here; what would happen?" It’s a subtle difference, but it matters. An allegory is a one-to-one code. A supposal is an exploration.

And then there's the reading order. This is the hill many Narnia fans will die on. If you buy a boxed set today, it’s usually numbered by the internal chronology of the world, starting with The Magician’s Nephew.

🔗 Read more: Why Standing on the Moon Lyrics Still Break Your Heart Every Time

This is a mistake.

It’s actually a huge mistake. The Magician’s Nephew is a prequel. It explains where the lamp-post came from. It explains the origin of the Witch. If you read that first, you completely spoil the mystery of the wardrobe in the first book. Lewis wrote The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe first. Then he wrote Prince Caspian. Then The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. He didn't even write the prequel until nearly the end. Reading them in "chronological order" is like watching the Star Wars prequels before the original trilogy. It robs the story of its magic.

The Inklings and the Brutal Critique

Lewis didn't write these in a vacuum. He was part of a writing group called The Inklings. They’d meet at a pub in Oxford called the Eagle and Child—they called it the "Bird and Baby"—and drink beer while reading their drafts out loud.

J.R.R. Tolkien was there.

Tolkien actually kind of hated Narnia.

Imagine being C.S. Lewis and showing your best friend your new book, and the guy who wrote The Lord of the Rings tells you it’s a mess. Tolkien thought Narnia was too "slapdash." He hated that Lewis mixed mythologies. You’ve got Father Christmas showing up in the same world as Greek dryads, Talking Beasts, and a Turkish-inspired villainy in the later books. To Tolkien, who spent decades building languages and tectonic plates for Middle-earth, Lewis’s world-building felt lazy.

But that’s exactly why it works for everyone else. Narnia isn't a museum. It’s a dream. It’s a "kitchen sink" mythology that feels alive because it’s so chaotic. Lewis didn't care about the linguistics of the Telmarines; he cared about the feeling of Turkish Delight and the cold crunch of snow.

The Books vs. The Movies: A Complicated Relationship

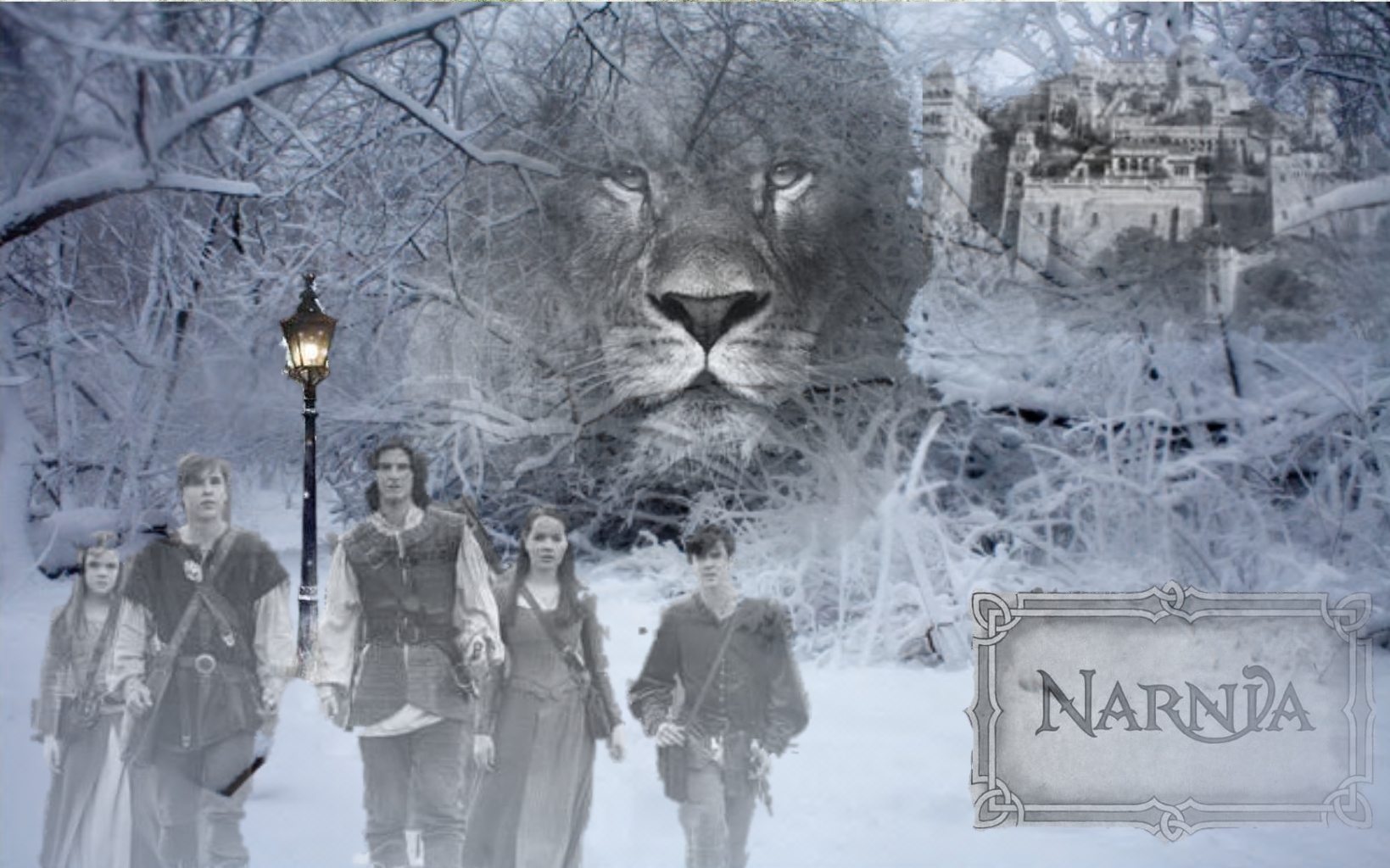

When Walden Media and Disney released The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in 2005, it was a massive hit. It captured that specific, high-fantasy aesthetic that Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings had popularized. But as the sequels rolled out, things got bumpy.

🔗 Read more: Bea Arthur in Star Wars: What Really Happened at the Mos Eisley Cantina

Prince Caspian (2008) tried to be "dark and edgy." They aged up the actors. They added a weird, forced romance between Susan and Caspian that was never in the books. It felt like the studio was scared that the source material was too "kiddy." By the time The Voyage of the Dawn Treader came out in 2010, the franchise was losing steam.

The problem is that Narnia is fundamentally episodic and philosophical. It doesn't always fit the three-act blockbuster structure. Take The Silver Chair, for example. It’s basically a subterranean road trip with a depressed Marsh-wiggle named Puddleglum. It’s weird. It’s claustrophobic. It’s brilliant. But Hollywood finds it hard to market a hero who spends half the time complaining about how they’re probably going to die in a hole.

Why We Are Still Talking About Narnia in 2026

It’s the longing. Lewis had a word for it: Sehnsucht. It’s that bitter-sweet desire for something you can’t quite name.

When Lucy looks into the back of the wardrobe and feels the fur of the coats turn into pine needles, every reader feels that. It’s the idea that the mundane world—the world of taxes, exams, and rain—isn't the only thing there is.

Even the "problematic" elements of the books, which critics like Philip Pullman have hammered for years, haven't managed to kill their popularity. People point out the depiction of the Calormenes or the "Problem of Susan" (the fact that Susan Pevensie is essentially "kicked out" of Narnia for liking lipstick and boys). These are valid criticisms. Lewis was a man of his time, and his biases show up in the ink. But the core of the story—the idea of courage, the sacrifice of the Lion, the concept of a world where animals talk and justice eventually wins—that stuff is evergreen.

The Netflix Reboot: What’s Actually Happening?

For years, Narnia has been in "development hell." Netflix bought the rights to all seven books back in 2018. It was a huge deal because it was the first time one company owned the rights to the entire catalog.

Then things went quiet.

Until Greta Gerwig signed on.

The director of Barbie and Little Women is set to direct at least two Narnia films. This is a fascinating choice. Gerwig is known for her deeply human, character-driven storytelling. She isn't a "CGI spectacle" director by trade. If anyone can fix the "Problem of Susan" or make the theological themes feel grounded and modern without losing the magic, it’s probably her.

Reports suggest production is gearing up, but don't expect a trailer tomorrow. They are taking their time to get the "vibe" right. Narnia needs to feel tactile. It needs to feel like old wood and cold stone, not a green-screen void.

Surprising Details You Probably Forgot

- The Wardrobe was real: It was based on a massive, dark oak wardrobe that Lewis’s grandfather made. It sat in Lewis's house, "The Kilns," and he and his brother used to climb inside it as kids.

- Aslan wasn't always a lion: Lewis struggled with the "savior" figure for a long time. He once said the lion "pounced" into his imagination and completed the story.

- The Shadowlands: The final book, The Last Battle, is deeply controversial. It features the literal end of the world. It’s heavy stuff for a "children's series."

- Puddleglum was based on a real person: Lewis’s gardener, Fred Paxford. He was a man who was perpetually pessimistic but incredibly kind-hearted.

How to Experience Narnia Today

If you’re looking to dive back into The Chronicles of Narnia, don't just watch the movies.

- Read the books in publication order. Start with The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. Move to Prince Caspian, then Dawn Treader, The Silver Chair, The Horse and His Boy, The Magician’s Nephew, and finally The Last Battle.

- Listen to the Focus on the Family Radio Theatre versions. Seriously. They are incredible. They have a full cast, a dynamic score, and they stay incredibly faithful to the prose. It’s much better than most of the film adaptations.

- Check out "The Kilns." If you’re ever in Oxford, you can visit Lewis’s home. Seeing the environment where he wrote these stories helps you understand the "Englishness" of the books—that specific mixture of cozy domesticity and wild, ancient myth.

Narnia persists because it’s a story about growing up without losing your soul. Lewis famously said that "a children's story which is enjoyed only by children is a bad children's story." He was right. Whether you’re eight or eighty, the idea that there is a door somewhere that leads to a place where you are a King or a Queen—and where a Great Lion knows your name—is something we never really outgrow.

👉 See also: Why Ozzy Osbourne Speak of the Devil Songs Still Matter

The next step for any fan is to go back to the source. Pick up a copy of The Silver Chair. It’s arguably the most "modern" and psychologically interesting book in the series, featuring a villain who uses gaslighting and enchantments rather than just raw power. It’s the perfect bridge between the childhood nostalgia of the first book and the deeper, darker themes Lewis explored at the end of his life. Read it again. You’ll find things you missed when you were ten. That’s the real magic of Narnia—it grows with you.