It happened at 1:23 a.m. Most of the world was asleep, totally unaware that a routine safety test in northern Ukraine was about to go sideways in a way that would rewrite human history. We’ve all seen the grainy footage or the HBO miniseries, but the reality of the Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster is actually a lot messier, more technical, and frankly, more terrifying than the dramatized versions suggest. It wasn't just a "mistake." It was a catastrophic collision of flawed technology, immense political pressure, and a series of human decisions that, in hindsight, seem almost suicidal.

Think about the RBMK-1000 reactor. It was the pride of Soviet engineering.

But it had a fatal flaw.

The "Positive Void Coefficient." Basically, in most Western reactors, if the coolant (water) disappears or turns to steam, the nuclear reaction slows down. It’s a natural brake. In the Chernobyl RBMK design, it was the opposite. More steam meant a faster reaction. It was like a car that accelerates the harder you hit the brakes.

The Night Everything Broke

The crew was trying to see if the turbines could provide enough power to run the cooling pumps during a blackout. Simple enough, right? Except the test had been delayed by ten hours. By the time Alexander Akimov and Leonid Toptunov took over the night shift, the reactor was in a poisoned state. Xenon-135, a byproduct of fission that eats up neutrons, had built up. The reactor was sluggish. It was dying.

To get the power back up, they pulled out almost all the control rods.

You’ve got to understand how risky this was. Anatoly Dyatlov, the deputy chief engineer, was reportedly pushing the crew hard. He wanted that test finished. Imagine trying to drive a massive truck down a steep hill while the engine is stalling, so you take your foot off the brake entirely just to keep it moving. That’s what happened in Reactor 4.

When they finally started the test, the water flow decreased. Steam bubbles formed. Because of that "Positive Void Coefficient," the power started to spike. Toptunov or Akimov—accounts vary on who reacted first—hit the AZ-5 button. The emergency shutdown. This should have saved them.

It didn't.

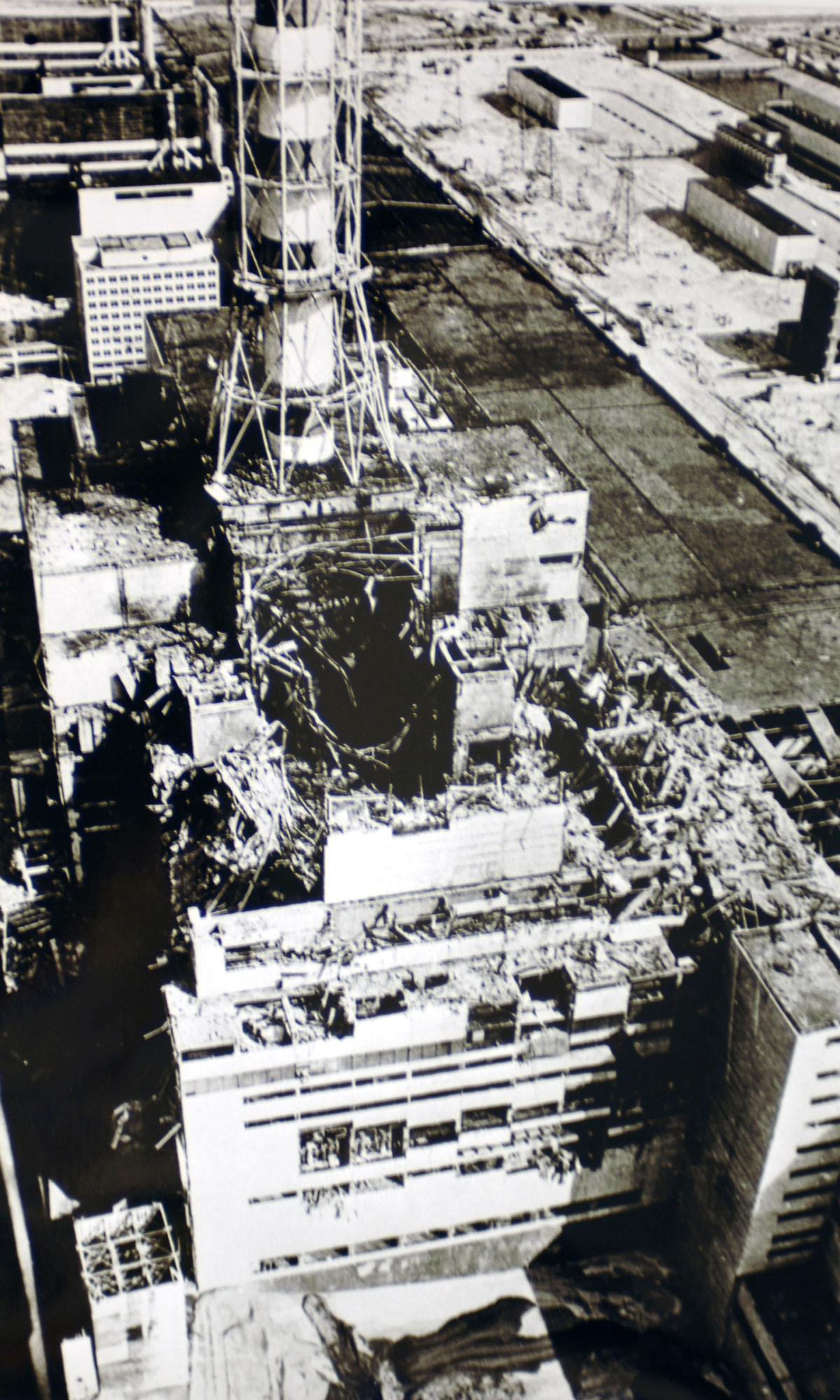

The control rods had graphite tips. For a split second, as those tips entered the core, they actually increased the reaction instead of damping it. The power surged to over 100 times its rated capacity. The fuel rods shattered. The steam pressure blew the 2,000-ton lid off the reactor like a bottle cap. Seconds later, a second explosion—likely hydrogen—tore through the building, exposing the burning core to the night sky.

The Fallout Nobody Saw Coming

Radiation isn't like a fire you can just douse. It’s invisible. It’s silent.

The firefighters who arrived first, like Vasily Ignatenko, had no idea they were walking into a death trap. They weren't told it was a nuclear fire; they thought it was a roof fire. They were picking up chunks of glowing graphite with their bare hands. Graphite that had been inside the core moments before. Honestly, the bravery of those "liquidators" is the only reason half of Europe isn't a dead zone today.

By the time the Soviet government admitted something was wrong—only after a Swedish nuclear plant detected high radiation levels 800 miles away—the city of Pripyat was already soaked in isotopes.

Pripyat was a model city. It had 50,000 people, parks, and a brand-new Ferris wheel that was supposed to open for May Day. People were out on their balconies watching the pretty colors of the ionized air above the reactor. They called it "the glow." They had no idea they were breathing in Iodine-131 and Cesium-137.

When the evacuation finally happened, they were told it was temporary. "Leave your things," the announcements said. They never went back.

Why the Deaths Are Still Debated

If you look at the official UN-backed reports (like the Chernobyl Forum), they cite fewer than 50 direct deaths and maybe 4,000 long-term cancer deaths. But if you talk to groups like Greenpeace or local Ukrainian scientists, they’ll tell you the number is closer to 90,000 or even higher.

Who's right?

It’s complicated. Low-dose radiation is notoriously hard to track. How do you prove a specific person’s thyroid cancer was caused by the Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster and not by lifestyle or genetics? You can't, really. But the spike in thyroid cancer among children in Belarus and Ukraine after 1986 is undeniable. The government waited too long to hand out potassium iodide pills, which would have blocked the thyroid from absorbing the radioactive iodine. That’s a failure of bureaucracy, not just physics.

The Technology of the Sarcophagus

The first "Sarcophagus" was a rush job. It was a concrete shell built by robots and men in lead suits who could only work for 40 or 90 seconds at a time because the radiation was so intense. It was never meant to last.

By the 2000s, it was crumbling.

Enter the New Safe Confinement (NSC). This thing is a marvel of modern technology. It’s the largest movable land-based structure ever built. It looks like a giant silver hangar. They built it away from the reactor to protect the workers and then slid it into place on rails in 2016. It’s designed to last 100 years, giving us enough time to eventually dismantle the mess inside.

But there’s a catch. Inside that shell, the "Elephant’s Foot" still sits. It’s a mass of corium—melted fuel, concrete, and metal. In 1986, just 300 seconds of exposure to it was fatal. Even now, it’s still hot, literally and radioactively.

Myths vs. Reality

People think Chernobyl is a barren wasteland.

It’s actually the opposite.

Without humans around, the 30km Exclusion Zone has become an accidental nature reserve. Wolves, lynx, and the endangered Przewalski's horses are thriving. There’s something eerie but beautiful about seeing a forest grow through the floor of a Soviet schoolhouse. However, don't let the Instagram photos fool you; the animals have higher rates of tumors and genetic mutations. It’s a "plastic" kind of recovery.

Also, the "Red Forest." It’s called that because the trees turned ginger-brown and died from the radiation immediately after the blast. It’s still one of the most contaminated spots on Earth. If a forest fire breaks out there today—which happens—it kicks all that old Cesium back into the atmosphere.

What This Taught Us About Nuclear Safety

The Chernobyl nuclear reactor disaster didn't kill the nuclear industry, but it forced it to grow up.

- Passive Safety: Modern reactors are designed so that if things go wrong, the physics of the system naturally shuts it down.

- Containment: Western reactors almost always have a thick reinforced concrete containment dome. Chernobyl didn't. If Reactor 4 had been inside a Western-style containment building, the world might never have heard the name Chernobyl.

- Culture of Safety: The "Human Factor" is now recognized as being just as important as the "Hardware Factor."

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you're fascinated by the history or looking to understand the risks of nuclear energy today, here is what you actually need to know:

👉 See also: What is the Definition of a Magnet (And Why It’s More Than Just Fridge Art)

- Check the Sources: When reading about radiation, look for data from the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) or the UNSCEAR reports. They provide the most rigorous, peer-reviewed data, even if their death toll estimates are more conservative than activist groups.

- Understand "Dose": Radiation is everywhere. You get more radiation from a cross-country flight or a CT scan than you do from standing outside the Exclusion Zone for a day. Context matters.

- The Future is Small: If you're worried about another Chernobyl, look into Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). These are the next generation of tech designed to be "walk-away safe," meaning they don't require human intervention or power to stay cool during an emergency.

- Visit Responsibly: You can actually tour Chernobyl (under normal geopolitical conditions). If you go, follow the rules. Don't touch the moss—it acts like a sponge for isotopes—and stay on the paved paths.

The disaster wasn't just a failure of a machine. It was a failure of a system that prioritized secrecy and speed over safety and truth. We’re still cleaning up the mess, and we probably will be for another few centuries. It’s a permanent scar on the planet, serving as a reminder that when we split the atom, we're playing with the fundamental forces of the universe. We can't afford to be arrogant.