You probably have a souvenir from a beach trip or a local pizza place stuck to your refrigerator. It’s a boring, everyday object. But honestly, if you stop and think about it, magnets are kinda terrifyingly cool. We are talking about an invisible force that can move physical objects through a vacuum or a solid wall. It feels like magic, but it’s actually just a very specific behavior of electrons.

So, what is the definition of a magnet?

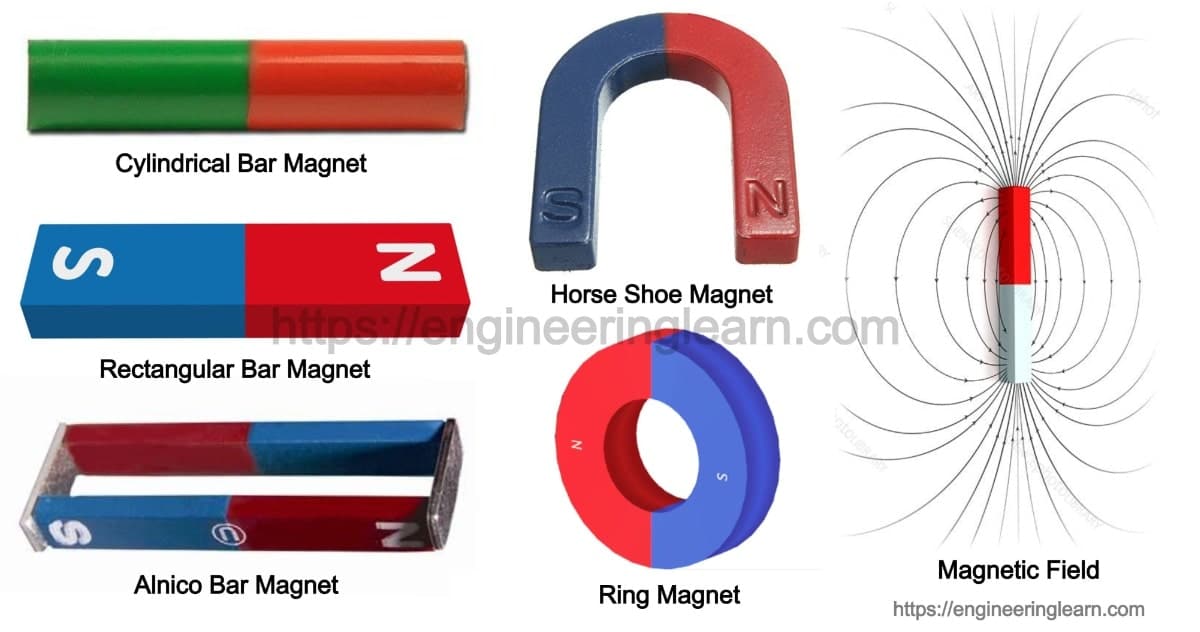

At its most basic, a magnet is any material or object that produces a magnetic field. This field is invisible, but it’s responsible for the most notable property of a magnet: a force that pulls on other ferromagnetic materials, like iron, steel, nickel, and cobalt, and attracts or repels other magnets.

The Invisible Field: Where the Magic Happens

Every magnet has two poles. We call them North and South. It’s a bit of a naming convention, but it’s based on how magnets interact with the Earth. If you hang a bar magnet by a string, it’ll eventually align itself with the Earth's magnetic poles.

Magnetic fields are vector fields. That sounds complicated, but it just means the force has both a strength and a direction. It flows out of the North pole and loops back into the South pole. You've probably seen those school experiments with iron filings. You sprinkle the dust over a piece of paper with a magnet underneath, and suddenly, the invisible lines become visible. It’s like seeing the skeleton of a ghost.

Why does this happen? It’s all down to electron spin.

In most materials, electrons are paired up and spin in opposite directions, effectively canceling each other out. Their magnetic moments are a mess. They point everywhere and nowhere. But in a magnet, the atoms are grouped into "domains." In these tiny pockets, the magnetic moments of the atoms all point in the same direction. When you get enough of these domains to line up, you get a macroscopic magnet.

💡 You might also like: Why Your 3-in-1 Wireless Charging Station Probably Isn't Reaching Its Full Potential

The Different "Flavors" of Magnetism

Not all magnets are created equal. You can’t just pick up a rock and expect it to hold up your grocery list.

First, you’ve got Permanent Magnets. These are the ones we know best. They stay magnetized once they’ve been "charged." Think of alnico (aluminum, nickel, and cobalt) or neodymium. Neodymium magnets are the heavy hitters. They are rare-earth magnets and are shockingly strong for their size. If you get two large neodymium magnets stuck together, you might need a literal power tool to get them apart. Or you might lose a fingertip. Seriously.

Then, there are Temporary Magnets. These are materials that act like magnets only when they are inside a strong magnetic field. If you rub a paperclip against a strong magnet, that paperclip will be able to pick up other paperclips for a little while. But eventually, the atomic domains lose their alignment, and the "magic" fades.

Lastly, we have Electromagnets. This is where things get high-tech. By running an electric current through a wire coil, you create a magnetic field. Wrap that wire around an iron core, and you’ve got a magnet you can turn on and off with a switch. This is the technology that makes your doorbell ring, runs the motors in your Tesla, and allows MRI machines to see inside your brain without cutting you open.

What Most People Get Wrong About Magnets

A common misconception is that magnets "stick" to all metals. They don't.

Try sticking a magnet to a soda can (aluminum) or a gold ring. Nothing happens. Magnetism is picky. It specifically loves "ferromagnetic" materials. There are also "paramagnetic" materials that are weakly attracted to magnets and "diamagnetic" materials (like copper or water) that are actually slightly repelled by them.

📖 Related: Frontier Mail Powered by Yahoo: Why Your Login Just Changed

Another weird fact: you cannot have a monopole. If you take a bar magnet and snap it perfectly in half, you don't get a "North" piece and a "South" piece. You get two smaller magnets, each with its own North and South pole. You can keep cutting until you're at the atomic level, and you'll still have two poles. Physics just doesn't allow for a "one-sided" magnet in our current understanding of the universe, though scientists are still hunting for the elusive magnetic monopole in particle accelerators.

The Earth is a Giant Magnet (And It’s Getting Weird)

We live on a massive magnet. The Earth’s core is a swirling mess of liquid iron and nickel. This movement creates electric currents, which in turn create a massive magnetic field that extends far out into space. This is the magnetosphere.

It’s our shield. Without it, the solar wind would strip away our atmosphere, and we’d be fried by radiation.

But here’s the kicker: the Earth’s magnetic poles move. Right now, the Magnetic North Pole is creeping from the Canadian Arctic toward Siberia at about 34 miles per year. Historically, the poles have even flipped entirely. The North became the South. It happens every few hundred thousand years. We’re actually overdue for a flip, which would be a total nightmare for our satellite navigation systems.

Magnets in Modern Technology

We use magnets in ways you probably never notice.

- Data Storage: Your old-school hard drives use tiny magnetic grains to store bits of data.

- Maglev Trains: In Japan and China, some trains literally levitate. They use powerful electromagnets to hover above the tracks, eliminating friction and allowing for speeds over 370 mph.

- Speakers: Every time you hear music, a magnet is pushing and pulling a coil attached to a cone, vibrating the air to create sound waves.

- Medicine: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) uses superconducting magnets cooled by liquid helium to flip the protons in your body’s water molecules.

How to Test Your Own Materials

If you're curious about the magnetic properties of things around your house, you can do a simple "scratch test" or a "float test."

👉 See also: Why Did Google Call My S25 Ultra an S22? The Real Reason Your New Phone Looks Old Online

Take a strong neodymium magnet and bring it close to various objects. You’ll notice that some stainless steels are magnetic while others aren't, depending on their nickel and chromium content.

If you want to get really nerdy, try the "Copper Pipe Trick." Drop a small, strong magnet through a vertical copper pipe. Copper isn't magnetic, so the magnet shouldn't stick. But as the magnet falls, its moving magnetic field creates "eddy currents" in the copper. These currents create their own magnetic field that opposes the falling magnet. The result? The magnet floats slowly down the pipe as if it's falling through honey. It’s a perfect, tangible demonstration of Lenz’s Law.

Actionable Insights for Using Magnets Safely

Magnets are tools, and like any tool, they require a bit of respect, especially as they get stronger.

- Keep them away from electronics: While modern SSDs and iPhones are more resilient than old floppy disks, powerful magnets can still interfere with sensors, speakers, and mechanical parts in laptops.

- Mind the "Pinch Hazard": Neodymium magnets (N52 grade and above) can snap together with enough force to shatter or crush skin. Always slide them apart rather than trying to pull them straight off.

- Storage: If you’re storing powerful magnets, keep them in a "keepered" state—attach them to a piece of iron or keep them in a non-conductive box so their field doesn't inadvertently grab passing metal objects.

- Heat Kills Magnetism: Most permanent magnets lose their strength if they get too hot. This is known as the Curie temperature. For a standard neodymium magnet, this is around 80°C (176°F). Don't leave them in a hot car or near an oven.

Understanding the definition of a magnet is really about understanding the fundamental relationship between electricity and motion. It’s the backbone of the modern world, hidden in plain sight.

Next Steps for Exploration

- Identify the difference between "N" ratings on magnets; N35 is standard, while N52 is the strongest commercially available grade.

- Check your household appliances—motors in blenders, vacuums, and fans all rely on the interaction between permanent magnets and electromagnets.

- Observe the "Curie Point" by safely heating a small magnetized needle (using pliers and a candle) until it no longer sticks to a metal surface, demonstrating how thermal energy disrupts atomic alignment.