You’ve probably heard someone say, "I don't want a raise because it’ll push me into a higher tax bracket and I’ll actually take home less money."

Honestly? That is one of the biggest myths in Canadian finance.

It's just not how it works. Canada uses a progressive tax system, which basically means you only pay the higher rate on the dollars that actually fall into that specific "bucket." If you earn $1 over a threshold, only that single dollar is taxed at the higher rate. The rest of your income stays right where it was.

📖 Related: How Much Will an Annuity Pay? What Most People Get Wrong

For 2026, things are looking a bit different than they did a couple of years ago. The federal government has finalized a cut to the lowest bracket, dropping it from the old 15% down to 14%. Because they phased this in halfway through 2025, last year felt a bit weird with a "prorated" rate of 14.5%. Now, in 2026, the 14% rate is fully in effect for the whole year.

The 2026 Federal Salary Tax Brackets Canada Breakdown

Every year, the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) nudges the thresholds upward to account for inflation. This is called indexing. For 2026, they've used an indexing factor of 2.0%.

If you’re looking at your federal tax bill, here is how the math shakes out for the 2026 tax year:

On the first $58,523 of your taxable income, the rate is 14%.

Once you pass that, the portion of your income between $58,523 and $117,045 is taxed at 20.5%.

For the mid-to-high earners, the next chunk from $117,045 up to $181,440 gets hit with a 26% rate.

If you’re doing quite well and earning between $181,440 and $258,482, that portion sees a 29% tax rate.

Anything over that $258,482 mark? That’s the top tier, taxed at 33% federally.

But remember, that’s just the federal side of the coin. You’ve also got provincial taxes to worry about, and those vary wildly depending on whether you're in a high-tax province like Quebec or a lower-tax environment like Nunavut.

Why the Basic Personal Amount is your best friend

Before you even start counting those brackets, there is a "zero" bracket. It’s called the Basic Personal Amount (BPA). Basically, this is the amount of money the government decides you need just to survive, so they don't tax it at all.

For 2026, the maximum federal BPA has increased to $16,452.

If you earn less than that, you owe zero federal income tax. Simple.

There is a catch, though. If you’re a high earner—specifically if your net income is over $181,440—the government starts "phasing out" that extra bump in the BPA. By the time you hit the top bracket ($258,482), your BPA drops back down to a base level of $14,829.

The Provincial Layer: Where it gets complicated

You can't just look at the federal numbers and call it a day. In Canada, your employer (or the CRA) looks at where you live on December 31. That province gets to take its cut too.

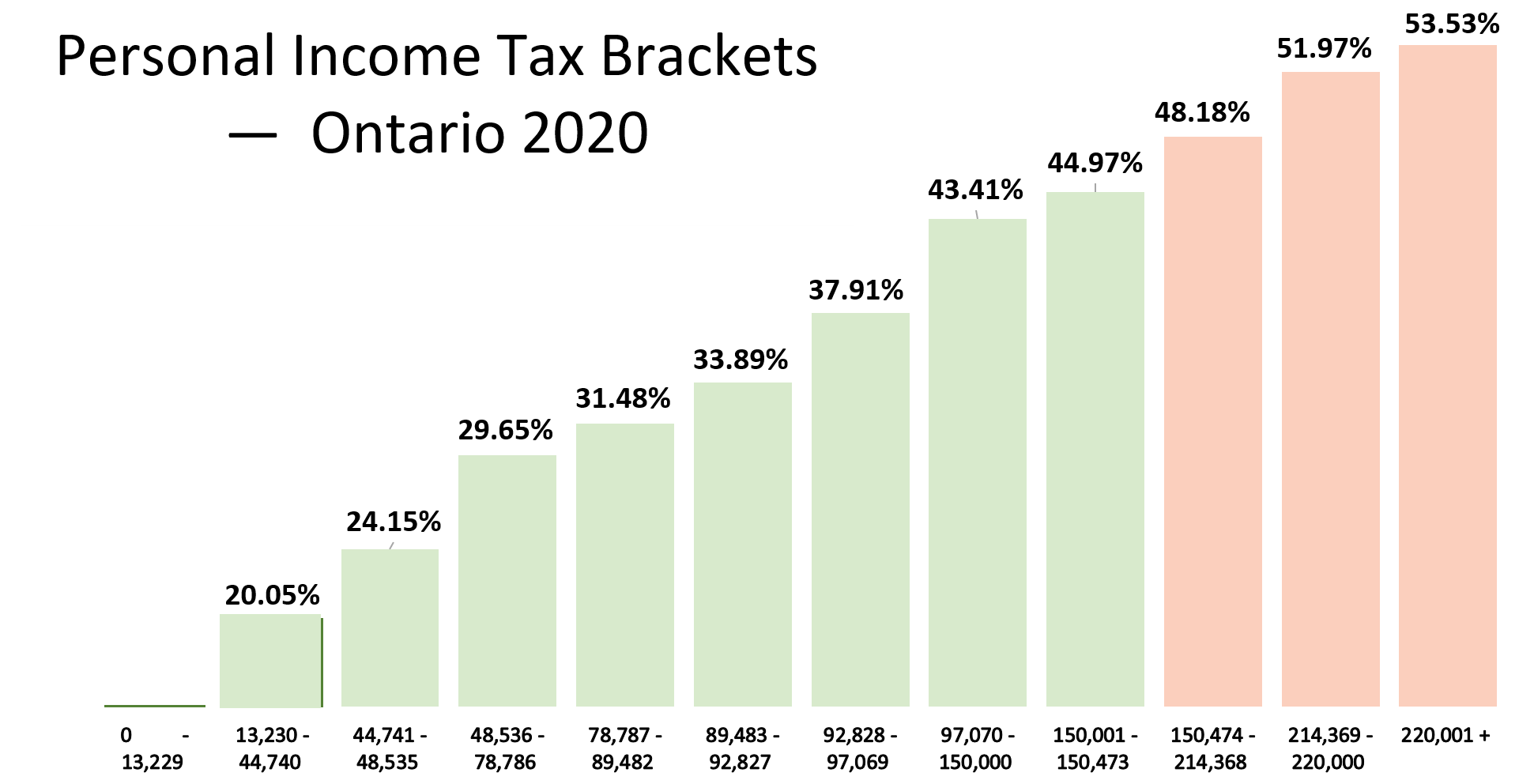

Take Ontario, for instance. Their brackets for 2026 start at 5.05% for the first $53,891. If you live in British Columbia, you’re looking at 5.06% for the first $50,363.

Alberta is an interesting case this year. They’ve been rolling out an 8% bracket for the first $61,200 of income, which is a bit of a shift for them. They’re trying to keep that "Alberta Advantage" alive, though their higher brackets still climb up to 15% once you're earning over $370,220.

Then there is Quebec. They have their own separate tax system entirely. While the other provinces have their tax collected by the CRA, Quebecers file two returns. For 2026, Quebec's lowest provincial rate is 14% on income up to $54,345. It sounds high, but they have different credits and a federal tax abatement that balances things out a bit.

A quick look at the "Marginal" vs "Effective" rate

This is where people get confused.

💡 You might also like: Split the Difference: Why This Classic Negotiation Move Is Actually a Trap

Your marginal tax rate is the tax you pay on the very next dollar you earn. If you’re in the second federal bracket and living in Ontario, your combined marginal rate might be around 29.65%.

Your effective tax rate, however, is the actual percentage of your total income that goes to the government. Because of the BPA and the lower brackets, your effective rate is always lower than your marginal rate.

For example, if you earn $60,000 in 2026:

- The first $16,452 is tax-free (Federal BPA).

- The next $42,071 is taxed at 14%.

- The final $1,477 is taxed at 20.5%.

Total federal tax: roughly $6,192.

Effective federal rate: about 10.3%.

See? Even though you "hit" the 20.5% bracket, you aren't paying anywhere near that on your whole salary.

Surprising details most people miss

One thing that often catches people off guard is "Bracket Creep." Inflation makes things expensive. If your boss gives you a 2% raise to keep up with the cost of milk and rent, but the tax brackets don't move, you'd actually end up poorer because more of your money would be pushed into higher brackets.

That’s why the CRA indexes the brackets. By moving the thresholds up by 2% in 2026, they are trying to ensure that your "real" purchasing power stays the same.

Also, don't forget the CPP and EI changes. These aren't technically "tax brackets," but they feel like taxes when they come off your cheque. In 2026, the Year's Maximum Pensionable Earnings (YMPE) for the Canada Pension Plan has climbed to $74,600. Plus, there is that "second tier" (CPP2) for income between $74,600 and $85,000. It’s an extra 4% contribution that caught a lot of people by surprise when it launched a couple of years ago.

💡 You might also like: Real Estate Agent Clipart: Why Your Brand Probably Looks Dated (and How to Fix It)

How to actually use this information

Knowing the brackets is useless if you don't do anything with it.

If you are right on the edge of a new bracket, that is the perfect time to look at RRSP contributions. Since RRSP contributions are deducted from your taxable income, they "wash away" the income from your highest bracket first.

If you earn $120,000, you are just barely into the 26% federal bracket. A $3,000 RRSP contribution could potentially pull your taxable income back down into the 20.5% bracket. You’re essentially getting a 26% "discount" (plus provincial tax) on that retirement saving.

On the flip side, if you're in the lowest bracket, an RRSP might not be your best move. You might be better off using a TFSA (Tax-Free Savings Account), where the limit for 2026 stays at $7,000. Why take a deduction now when your tax rate is only 14%? Better to save that RRSP room for later in your career when you're (hopefully) in a 29% or 33% bracket.

Actionable Steps for 2026

- Check your pay stub: Look at your year-to-date taxable income. Compare it to the 2026 thresholds ($58,523, $117,045, etc.) to see which marginal bracket you're currently sitting in.

- Adjust your TD1 forms: If you have major life changes—like a new child or a second job—update your TD1 forms with your employer so they aren't over-withholding (or under-withholding) tax.

- Maximize the "Low Tax" years: If you expect to earn more in the future, prioritize your TFSA. If this is a peak earning year, lean into the RRSP to dodge those 26%+ federal brackets.

- Account for the CPP2: If you earn over $74,600, expect a slightly smaller take-home pay later in the year as those second-tier contributions kick in.

Understanding the mechanics of the Canadian tax system takes the "fear" out of the math. Taxes are high, sure, but they are also predictable. By knowing exactly where the lines are drawn, you can stop worrying about raises and start focusing on how to keep more of what you earn.