You see the numbers flash on the screen every summer. Category 3. Category 4. Maybe even a 5. Most of us have been conditioned to think of these as a simple "bad to worse" scoreboard. But the truth is, the Saffir Simpson wind scale is way more complicated—and in some ways, more limited—than the 30-second weather clip on the local news makes it out to be.

Honestly, the scale is a bit of an old-school relic that’s been tweaked over the decades to keep up with how we actually build houses and measure air. It started back in 1971. A civil engineer named Herbert Saffir and a meteorologist named Robert Simpson teamed up because they realized people didn't really understand what a "hurricane" meant for their actual front porch. Saffir was the structural guy; he wanted to know if a roof would stay on. Simpson was the weather guy; he wanted to track the beast.

Why the numbers don't tell the whole story

Here’s the thing that trips people up: the scale is only about wind. Since 2010, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) officially renamed it the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale (SSHWS) because they stripped out things like storm surge and central pressure.

Why?

Because nature doesn't like being put in a box. You can have a "weak" Category 1 storm that dumps 40 inches of rain and floods an entire state—think Hurricane Florence in 2018. Or you can have a massive Category 2 like Hurricane Ike (2008) that pushes a 20-foot wall of water onto the coast, even though the wind speeds weren't "major."

If you only look at the category number, you're missing about 70% of the danger.

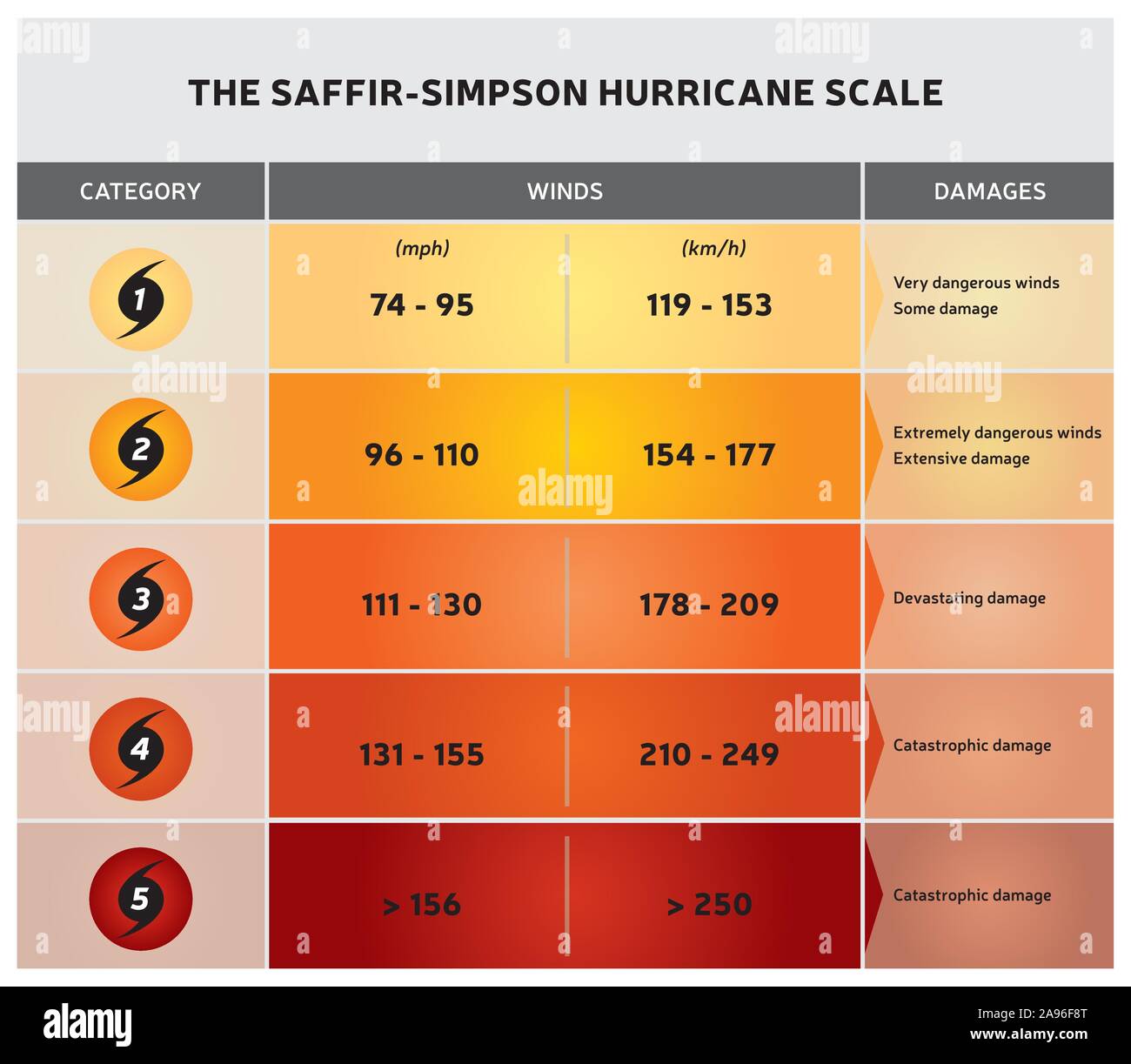

Category 1: 74-95 mph

Don’t let the "1" fool you. These are "very dangerous winds." You’re looking at shingles flying off, gutters getting ripped away, and shallow-rooted trees toppling over. Basically, your yard is going to be a mess, and you’ll likely lose power for a few days.

Category 2: 96-110 mph

This is where things get real. Well-constructed frame homes can take major roof and siding damage. It’s not just a "strong breeze" anymore; it’s enough force to snap power poles. If you have an older mobile home, a Category 2 is often the breaking point.

Category 3: 111-129 mph

Meteorologists call this a "Major Hurricane." At this level, the damage isn't just "some shingles"—it's "the roof decking is gone." Electricity and water are usually out for weeks. You’re not just cleaning up sticks; you’re rebuilding parts of your house.

Category 4: 130-156 mph

This is catastrophic. Think Hurricane Ian or Hurricane Helene. Most trees are snapped or uprooted. Power poles go down like toothpicks. Residential areas can become isolated because the roads are literally covered in debris and fallen infrastructure. It’s the kind of wind that makes a place uninhabitable for months.

Category 5: 157 mph or higher

There is no "worse" on the current scale. This is total destruction. A high percentage of framed homes will be destroyed, with total wall collapse and roof failure. It’s essentially a massive tornado that lasts for hours.

The "Category 6" Debate

Lately, there’s been a lot of chatter in the scientific community—led by researchers like Michael Wehner and James Kossin—about whether we need a Category 6.

The logic is pretty simple: the scale is open-ended. Right now, a 157 mph storm and a 215 mph storm (like Hurricane Patricia in 2015) are both "Category 5." But the destructive power of wind doesn't increase linearly. It's exponential.

If you double the wind speed, the force on a building doesn't just double—it quadruples. Some experts argue that as the oceans warm and storms get more "juice," we need a new tier for those 190+ mph monsters to better warn the public. Others think it’s pointless because once your house is leveled, it doesn't really matter if the wind was 160 or 190.

What you should actually watch for

If you're living in a strike zone, the Saffir Simpson wind scale should be your starting point, not your ending point.

- Check the Storm Surge: This is what actually kills the most people. A Category 1 with a 10-foot surge is deadlier than a Category 3 with a 3-foot surge.

- Look at the Size: Large storms (like Hurricane Sandy) spread their energy over a massive area, even if their peak winds aren't record-breaking.

- Speed of Motion: A slow-moving storm is a flood machine. If a Category 1 sits over your house for 24 hours, you’re in more trouble than if a Category 4 zips by in two hours.

The scale is a tool, not a crystal ball. It tells you about the wind's potential to peel back your roof, but it won't tell you if the creek in your backyard is going to end up in your living room.

📖 Related: South Loop Chicago News: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Next Steps:

- Get a NOAA Weather Radio: Don't rely on cell towers that might go down in a Category 2.

- Know your zone: Find your local evacuation zone based on flooding, not just wind category.

- Audit your roof: If you live in a hurricane-prone area, check your roof's "uplift" rating. Category 3 winds begin to expose structural weaknesses in standard shingles and gable ends.

- Ignore the "just a 1" talk: Treat every landfalling system as a multi-hazard event.