You’re standing on a beach. The tide suddenly retreats, exposing rocks and fish that were underwater just seconds ago. It looks cool, maybe even a little eerie. But honestly? If you see this, you need to run. That retreating water is the first sign that a massive displacement has happened miles out at sea. We all know the basic idea: earthquakes can cause tsunamis. But the "how" is way more violent and specific than just a big shake. It’s not about the shaking itself; it’s about the vertical shove.

The Vertical Shove: How Earthquakes Can Cause Tsunamis

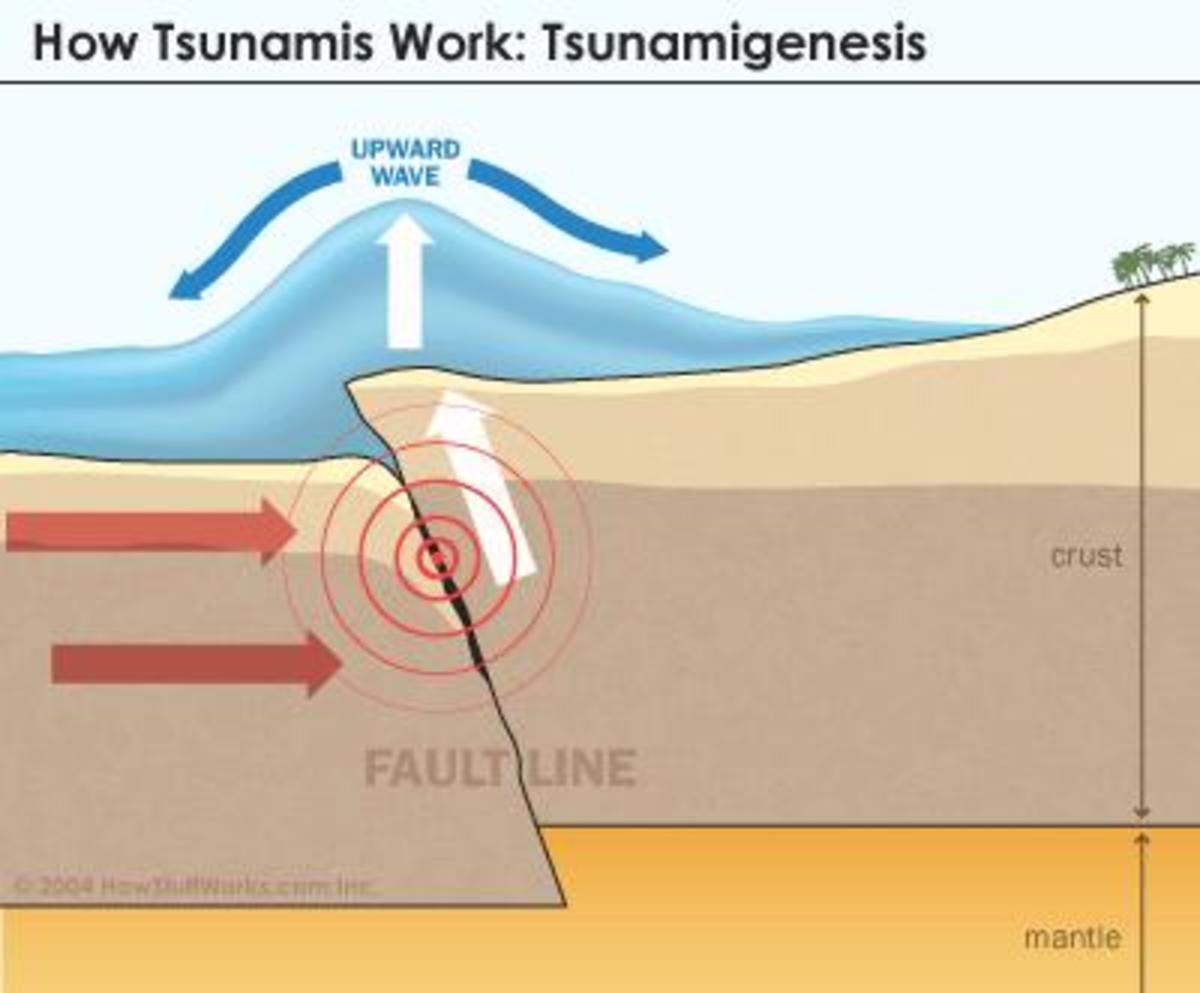

Not every quake is a tsunami-maker. You could have a massive magnitude 8.0 "strike-slip" earthquake—where two plates grind past each other horizontally—and the ocean might barely ripple. Why? Because to move a massive amount of water, you have to move the seafloor up or down. Think about it like a bathtub. If you slide your hand across the bottom, the water level doesn't change much. But if you suddenly punch upward? You’re getting wet.

Most of these world-altering waves happen at subduction zones. This is where one tectonic plate is forced under another. Sometimes, these plates get stuck. Tension builds for decades, centuries even. Then, in a terrifying snap, the overriding plate springs upward. This vertical displacement of the water column is the catalyst. The entire ocean, from the floor to the surface, is shoved. That energy has to go somewhere.

👉 See also: Why the UnitedHealthcare CEO Shooting Video Changed Everything We Know About Corporate Security

It's a Pulse, Not a Wave

We often picture a tsunami like a massive surfing wave with a curling crest. That’s a myth. In the deep ocean, a tsunami is barely noticeable. It might be only a foot high, but it’s hundreds of miles long and moving at the speed of a jet plane—around 500 miles per hour. Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) use Deep-ocean Assessment and Reporting of Tsunamis (DART) buoys to detect these pressure changes. These sensors sit on the ocean floor and can feel the weight of the water column changing above them.

When that pulse hits shallow water, everything changes. The front of the wave slows down because of friction with the seabed, but the back is still screaming along at hundreds of miles per hour. The wave "bunches up." It turns into a fast-moving wall of water that doesn't just crash and recede; it keeps coming for thirty minutes or more.

🔗 Read more: Where is the Airport Fire Burning Right Now and What You Need to Know

The Tōhoku Lesson

March 11, 2011. Japan. A magnitude 9.0 quake struck. It was one of the most well-documented geological events in human history. The Japan Trench saw the seabed jump upward by as much as 50 meters in some spots. That’s a five-story building’s worth of rock moving in an instant.

The resulting tsunami didn't just hit the coast; it overtopped sea walls that were designed for much smaller events. It showed us that our historical data is sometimes a "kinda" guess. We prepare for what we’ve seen before, but the Earth has a much longer memory than humans do. The Tōhoku event proved that earthquakes can cause tsunamis that defy our best engineering if we underestimate the potential "slip" of a fault line.

Dr. Costas Synolakis, a leading tsunami expert, has often pointed out that the sheer volume of water involved in these events is hard for the human brain to process. It’s not just water; it’s debris. It’s cars, houses, and ships turned into a liquid battering ram.

The "Big One" and the Cascadia Subduction Zone

If you live in the Pacific Northwest—Vancouver, Seattle, Portland—this isn't just academic. The Cascadia Subduction Zone is a 600-mile-long monster sitting just off the coast. It’s been quiet since January 26, 1700. We know the exact date because of "orphan tsunami" records in Japan and "ghost forests" of cedar trees in Washington that died when their roots were suddenly submerged in saltwater.

The geological community is basically certain it will happen again. When it does, the earthquake will likely last three to five minutes. That’s an eternity when the ground is moving. And then, the wave. In places like Seaside, Oregon, or Long Beach, Washington, the time between the shaking stopping and the water arriving could be as little as 15 to 20 minutes.

Why the "Shaking" is Your Only Warning

In many parts of the world, high-tech siren systems exist. But if you’re near the epicenter, the earthquake itself is your siren. If the ground shakes so hard that you can’t stand up, or if the shaking lasts for more than a minute, don’t wait for a text alert. Don't check Twitter. Move inland. Move high.

There's this common misconception that the first wave is the biggest. It rarely is. Tsunamis are a "train" of waves. The second or third surge can often be much larger than the first, and they can keep arriving for hours. People often die because they head back down to the beach to see the damage or help others after the first wave recedes. Don't be that person.

Misconceptions That Kill

- "I can outrun it." You can’t. Even if you're a fast runner, the water is moving faster than an Olympic sprinter and it's carrying a city's worth of trash.

- "The water will look like a wall." Sometimes it does, but often it just looks like a tide that won't stop rising. It’s deceptive and relentless.

- "Deep water is safe." If you’re in a boat, get to water at least 100 feet deep. If you’re at the dock, leave the boat and run. Trying to save your vessel is a death sentence.

Actionable Steps for Survival

Understanding that earthquakes can cause tsunamis is the first step, but being ready is what actually keeps you alive. It’s not about being a "prepper"; it’s about basic situational awareness.

👉 See also: A Deadly American Marriage: Why the Peterson Case Still Haunts Us

- Identify your zone. Look up tsunami inundation maps for your area. If you’re on vacation in a place like Hawaii, Indonesia, or the West Coast, look for the "Tsunami Evacuation Route" signs. They aren't just decorations.

- The 20-Minute Rule. If you feel a long earthquake (over 20 seconds of shaking), you likely have about 20 minutes to get to high ground if a tsunami was triggered.

- Go high or go inland. High ground is better. If there isn't any, go as far inland as possible. Vertical evacuation—climbing to the fourth floor or higher of a reinforced concrete building—is a last resort but a viable one.

- Grab your "Go Bag." You won't have time to pack. Have a bag with water, a radio, and your meds ready by the door.

- Stay there. Once you reach high ground, stay there for at least 12 hours unless local authorities give a clear "all clear."

The reality of how earthquakes can cause tsunamis is a stark reminder of how thin our margin of safety is. The Earth is active. It moves. We just happen to live on the wrinkly bits on top. Respect the power of the displacement, and if the ground starts to roll, get away from the shore.