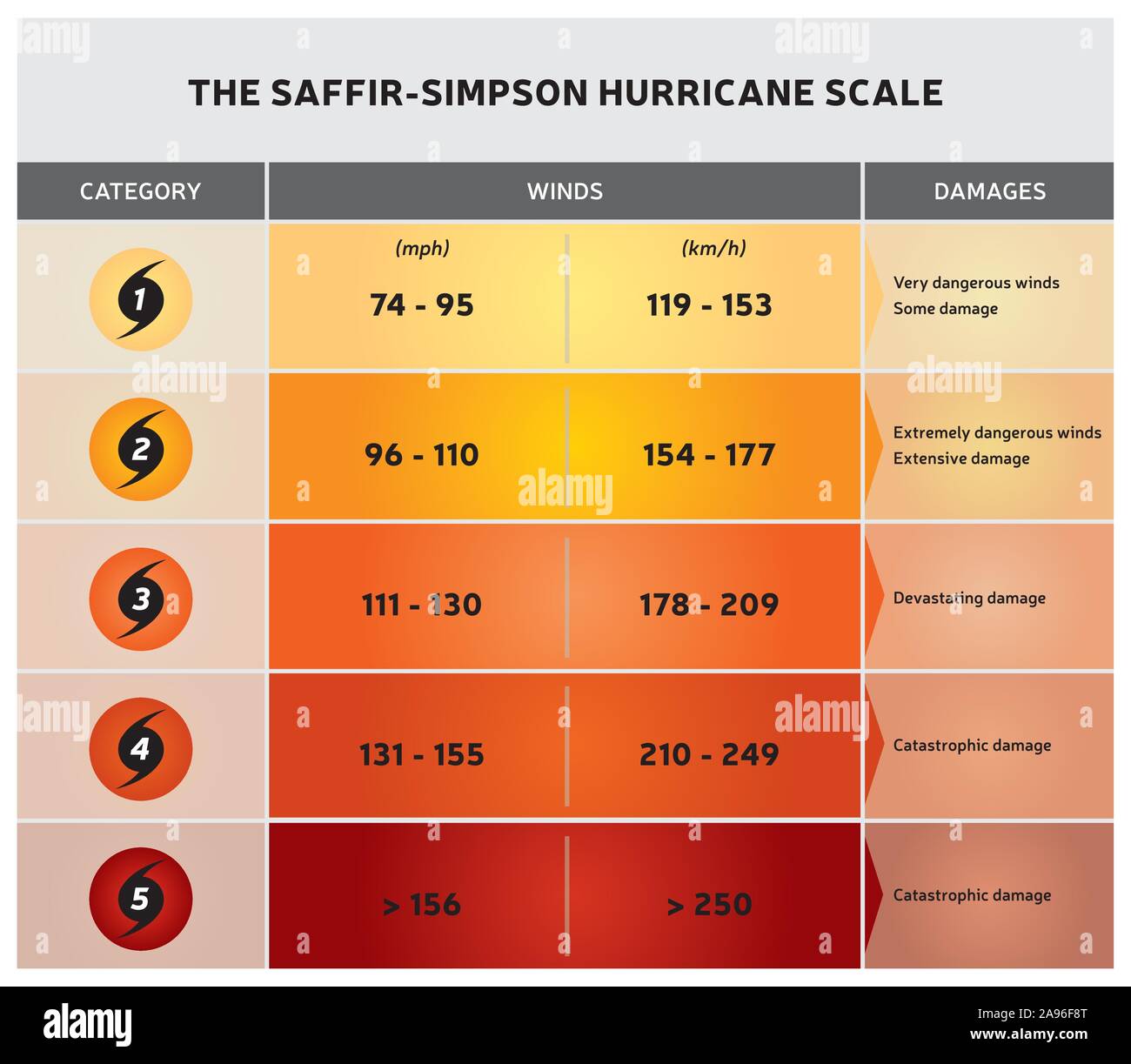

Honestly, whenever a hurricane starts spinning in the Atlantic, the first thing everyone asks is, "What category is it?" We’ve all seen the graphics on the news. Big colorful swirls. Numbers 1 through 5. It feels like a simple leaderboard for disasters. But here's the thing: the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is probably one of the most misunderstood tools in weather history.

It isn't a "total danger" meter.

People see a Category 1 and think they can just sleep through it with a few candles and some board games. Then, a few days later, they’re being rescued from a roof because of a twenty-foot storm surge. Why? Because the scale only measures one thing. Wind.

Where did this scale even come from?

Back in the early 1970s, an engineer named Herbert Saffir and a meteorologist named Robert "Bob" Simpson sat down to solve a problem. Saffir was looking at low-income housing and realized there was no easy way to describe how wind would actually wreck a building. He created a 1–5 scale based on structural damage.

Simpson, who was running the National Hurricane Center at the time, saw it and thought it was brilliant. He added the effects of storm surge and flooding. For decades, that’s what we used.

But science gets messy.

In 2010, the National Hurricane Center (NHC) actually stripped those extra parts away. They realized that a small, fast-moving "weak" hurricane could actually dump more rain or push more water than a massive, slow Category 4. So, they renamed it the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale. They made it strictly about "maximum sustained wind speed."

If you're looking at the category, you're looking at how fast the air is moving 33 feet above the ground. That's it.

💡 You might also like: Delaware Car Accident Yesterday: What Really Happened on Route 1 and Lakeview

The Category 1 Trap

"It's just a Cat 1."

Famous last words. A Category 1 hurricane has sustained winds of 74–95 mph. That’s enough to rip the shingles off your roof. It’ll toss your patio furniture through your neighbor's sliding glass door. It'll snap tree branches like toothpicks.

You’ve got to remember that the damage isn't linear. It’s logarithmic.

Basically, as you go up the scale, the power doesn't just double. It explodes. A Category 2 storm doesn't do twice the damage of a Category 1; it does about ten times more. By the time you hit Category 3—which is the threshold for a "major hurricane"—you’re looking at 111–129 mph winds. This is where well-built homes start losing their roof decking.

What the scale doesn't tell you

This is the part that kills people. Literally.

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale ignores:

- Storm Surge: The wall of water pushed toward the shore.

- Rainfall: Tropical systems can drop 40 inches of rain regardless of wind speed.

- Tornadoes: Hurricanes are basically giant tornado-manufacturing plants.

- Size: A huge Cat 2 is often more dangerous than a tiny Cat 4.

Think about Hurricane Katrina. When it hit Louisiana in 2005, it was a Category 3. People thought, "Okay, we’ve survived worse." But because it had been a Category 5 out in the Gulf, it had already built up a massive, catastrophic surge. The wind went down, but the water didn't care. It kept coming.

Then there’s the speed of the storm itself. If a hurricane is moving at 2 mph, it’s just sitting there. It’s grinding away at your house for 24 hours. A "stronger" Category 4 that zips by at 20 mph might actually do less structural damage because the house isn't being pounded for as long.

Breaking down the 2026 reality

We’re seeing more "rapid intensification" lately. That’s the fancy term for a storm going from a tropical waif to a Category 5 monster in less than a day.

👉 See also: Finding the Most Wanted New York Suspects: How the System Actually Works

Category 4 (130–156 mph) is where things get truly apocalyptic. Most of the trees will be snapped. Power poles will go down. You might not have electricity for weeks, maybe months. Residential areas often become uninhabitable for a long time.

Category 5 (157 mph or higher) is total destruction. It’s the end of the line. At these speeds, a high percentage of framed homes will just collapse. Most people who have lived through a direct hit from a Cat 5 say it doesn't even sound like wind anymore. It sounds like a freight train parked in your living room.

Practical ways to use the scale (without getting fooled)

You have to treat the category as a "wind damage estimate," not a "safety guide."

If the NHC says a Category 2 is coming your way, you shouldn't just think about your roof. You should be looking at the Integrated Kinetic Energy (IKE) or the surge maps. Honestly, the "cone of uncertainty" is another thing people mess up. They think if they aren't in the middle of the cone, they're safe.

The cone only shows where the center of the storm might go. The wind and rain (and the Saffir-Simpson effects) can stretch hundreds of miles outside that little white bubble.

What you should actually do:

- Check your roof age: If you're in a Category 1 zone and your roof is 20 years old, it’s gone. The scale assumes "well-constructed homes."

- Ignore the "it's only a..." talk: If you see a "weak" storm that is moving slowly, start worrying about water. Water is what usually causes the most fatalities.

- Secure the projectiles: In Category 2 winds, a loose brick or a birdfeeder becomes a bullet.

- Look for the "Major" label: Once it hits Category 3, evacuation orders usually become mandatory for a reason. Don't be the person on the news waiting for a helicopter.

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is a masterpiece of simplification. It’s great for a headline. But you’ve got to look past the number. If the wind is 95 mph (Cat 1) or 96 mph (Cat 2), your house doesn't know the difference. Both are going to be a very bad day if you aren't prepared.

Take the category seriously, but keep your eyes on the rainfall and surge forecasts too. That’s how you actually survive the season.

Next Steps for Your Safety Plan:

- Download the FEMA app: It provides real-time alerts and lets you see the specific surge risks for your zip code, which the Saffir-Simpson scale doesn't cover.

- Audit your "Wind Projectiles": Walk around your yard today. Anything not bolted down needs a home in the garage the moment a Tropical Storm warning (39-73 mph) is issued.

- Review your Insurance: Confirm if you have "Windstorm" coverage specifically. Many standard policies in coastal states have separate deductibles for Saffir-Simpson ranked events.