Look at the painting. You know the one. It’s usually a wide, sweeping landscape where the Cherokee people are trudging through the snow, wrapped in blankets, looking mournful but somehow... static. It’s the "classic" image of Trail of Tears history that most of us saw in a middle school textbook. But here’s the thing: most of those iconic paintings weren't even made by people who were there. They were painted decades—sometimes nearly a century—after the actual forced removals of the 1830s.

History is messy.

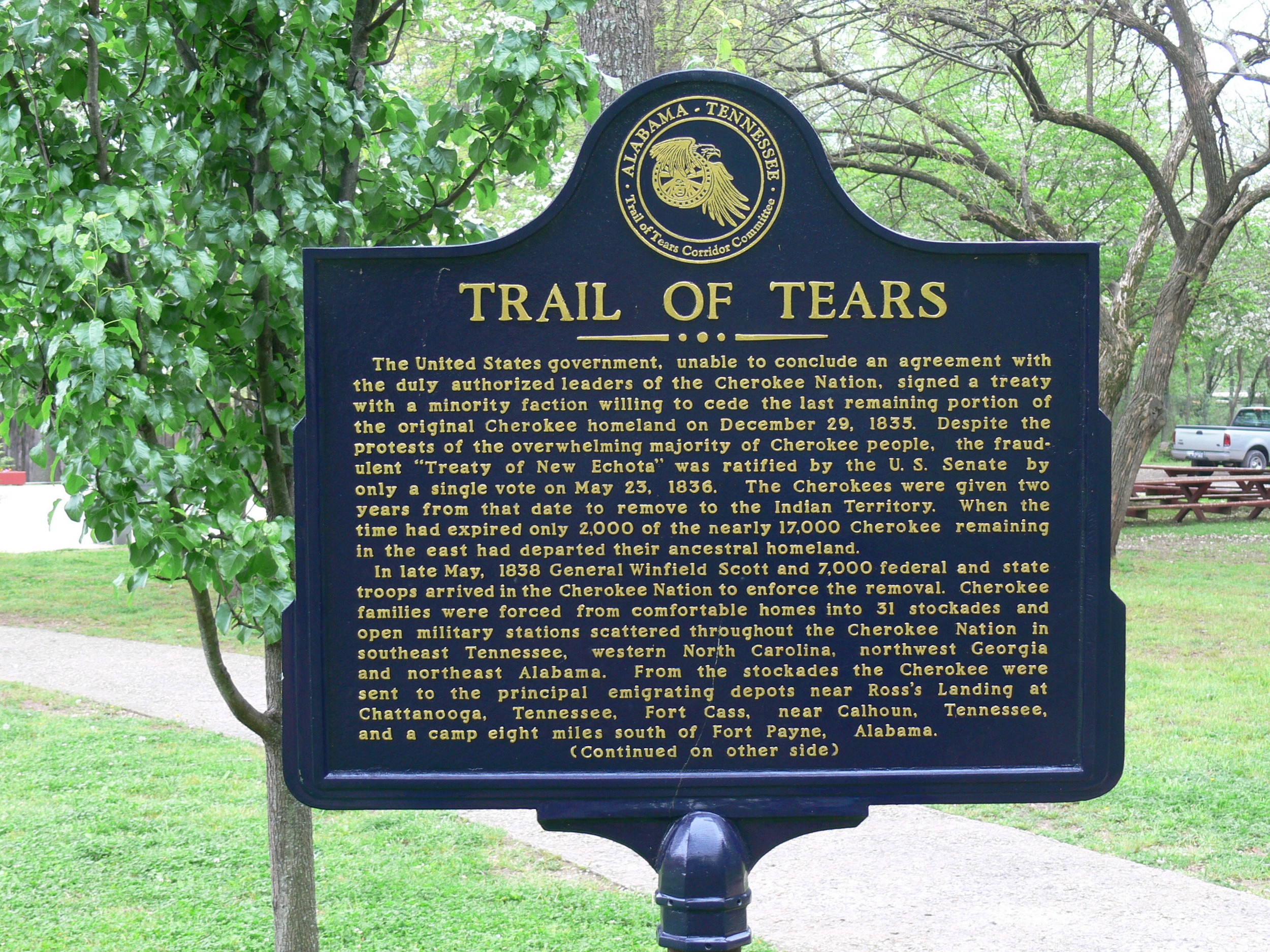

When we talk about the Trail of Tears, we aren’t just talking about one single walk or one single tribe. We are talking about the state-sponsored displacement of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations. If you’re looking for a real, unfiltered image of Trail of Tears suffering and survival, you won’t find it in a photograph. Photography was barely a baby in 1838. Louis Daguerre was just starting to figure out how to make images stick to silver plates in Paris while the Cherokee were being rounded up into stockades in Georgia.

Instead, our visual understanding comes from a mix of survivor accounts, modern archeology, and a few key artists who tried to capture the gravity of the event long after the dust had settled.

The Problem With the Paintings

Take Robert Lindneux’s famous 1942 painting. It’s arguably the most recognizable image of Trail of Tears tragedy in existence. You see the horses, the wagons, and the heavy wool blankets. It’s evocative. It’s sad. But it was painted over 100 years after the fact. Lindneux was a Western artist, and while his work helped keep the memory alive, it also romanticized the aesthetic of the "vanishing Indian."

We tend to lean on these images because the reality is harder to look at.

💡 You might also like: Wisconsin Judicial Elections 2025: Why This Race Broke Every Record

The actual visual record is found in the dirt. Archeologists at sites like Fort Cass in Tennessee have uncovered the literal footprints of this era. They find domestic items—shards of pottery, buttons, and tools—that people had to abandon or carry. This is the "image" of the trail that actually carries weight. It’s not a dramatic oil painting; it’s a broken piece of a ceramic plate left in the mud because a soldier told a mother she could only carry what fit in her arms.

What the Eyes Actually Saw

If you want an honest image of Trail of Tears life, you have to look at the written records of the people who were there, like Reverend Daniel Butrick. He traveled with the Cherokee and his journals are basically "word-paintings." He didn't write about "noble tragedy." He wrote about the smell of death. He wrote about the "constant sound of coughing" in the camps.

The removal happened in waves.

The "water route" was arguably more terrifying than the land route. Imagine hundreds of people crammed onto steamboats and flatboats on the Arkansas River. The heat was stifling. Cholera was everywhere. When we visualize this history, we usually think of a snowy forest, but a massive part of the image of Trail of Tears suffering happened on the water, where people died so quickly they were often buried in shallow, unmarked graves along the riverbanks during brief stops.

The Myth of the "One" Trail

People get this wrong all the time. There wasn't just one path.

📖 Related: Casey Ramirez: The Small Town Benefactor Who Smuggled 400 Pounds of Cocaine

- The Northern Route is the one most people recognize (through Illinois and Missouri).

- The Water Route used the Tennessee and Mississippi rivers.

- The Bell Route followed a more southern path.

- The Benge Route took another distinct trajectory through the Ozarks.

Every time someone searches for an image of Trail of Tears maps, they usually see a few clean lines. In reality, it was a chaotic web of movements. Some groups had better resources than others. Some were led by Cherokee leaders like John Ross, who tried desperately to maintain some semblance of order and dignity under impossible circumstances. Others were led by the U.S. military, which was often indifferent—or outright hostile—to the survival of their "charges."

The Modern Visual Legacy

So, what does a real image of Trail of Tears history look like today?

It looks like the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail. It’s over 5,000 miles of land and water routes across nine states. If you visit the Museum of the Cherokee Indian in North Carolina or the Cherokee Heritage Center in Oklahoma, the imagery changes. It moves away from the "victim" trope and toward "survivor."

We have to acknowledge the nuance.

The Cherokee Nation wasn't a primitive group of people wandering the woods. By 1838, they had a written constitution. They had a newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix. They had a higher literacy rate than many of the white settlers who were trying to steal their land. The true image of Trail of Tears loss is the destruction of a thriving, literate, and sovereign legal system.

👉 See also: Lake Nyos Cameroon 1986: What Really Happened During the Silent Killer’s Release

When you see a picture of the Cherokee Phoenix printing press being destroyed, that is just as much an "image" of the trail as a person walking in the snow. It represents the deliberate attempt to silence a voice that was using the law to fight back.

Why the "Trail Where They Cried" Matters Now

The term itself—Nunna daul Isunyi—literally means "The Trail Where They Cried." But it wasn't just the Cherokee. The Muscogee (Creek) removal was equally brutal, yet it gets less "screen time" in our collective memory. Their image of Trail of Tears history is often tied to the "Second Creek War," where they were rounded up in chains after resisting the fraudulent land grabs in Alabama.

Honestly, the way we consume these images today is kinda flawed. We look at them to feel a quick burst of empathy, then we close the tab. But the visual history is a warning about what happens when "expediency" and "national interest" are used to justify the suspension of human rights.

How to Correct the Lens

If you’re a teacher, a student, or just someone who cares about the truth, stop looking for the "saddest" picture. Instead, look for the most accurate ones.

- Prioritize Native Artists: Look at the work of contemporary Cherokee artists like Kay WalkingStick or Dorothy Sullivan. They provide a visual perspective that comes from inside the culture, not an outside observer trying to make a buck on a "tragic" scene.

- Read the Letters: The "visual" is in the detail. Read the letters of John Ridge or the petitions sent to Congress. They paint a picture of a people who were sophisticated, angry, and deeply connected to their ancestral homes.

- Visit the Actual Sites: Standing at Manty’s Ferry in Missouri or Berry’s Ferry in Kentucky gives you a sense of scale that no laptop screen can provide. The sheer width of the rivers they had to cross in mid-winter is terrifying.

The true image of Trail of Tears history isn't just a painting of a man in a blanket. It's the resilient face of the Cherokee Nation today—a tribe that didn't just "vanish" but rebuilt their entire society in a foreign land. They are still here. Their language is still spoken. Their government still functions. That is the ultimate image that should be in the textbooks.

Actionable Steps for Deeper Understanding

- Check your sources: If you're using an image of Trail of Tears history for a project, look for the artist's name and the year it was created. If it was made after 1900, it's a "historical reimagining," not a primary source.

- Support Tribal Museums: Places like the Choctaw Cultural Center provide the most accurate visual and oral histories of removal.

- Geolocate the History: Use the National Park Service’s interactive maps to see if a removal route passed through your own town. Seeing that a major highway today was once a path of forced migration changes how you look at your own backyard.

- Avoid Over-Simplification: Don't just focus on the Cherokee. Research the "Death March" of the Muscogee or the Seminole Resistance to get the full visual scope of the 1830s Southeast.

History isn't a static picture on a wall. It's a living, breathing record that we have to keep correcting. Every time we look past the romanticized paintings and toward the gritty, difficult truths of the primary sources, we get a clearer image of Trail of Tears reality.