You’ve probably seen the movie. Frank Sinatra as Nathan Detroit, Marlon Brando—somewhat controversially—singing as Sky Masterson. Maybe you’ve seen a high school production where the costumes were a little too shiny. But if you actually sit down and read the Guys and Dolls script, you realize it’s a whole different animal. It’s tight. It’s rhythmic. Honestly, it’s one of the few musical books that reads like a masterclass in vernacular comedy.

Most people assume the magic of the show is just the music by Frank Loesser. And yeah, the songs are incredible. "Luck Be a Lady" is a literal anthem. But the foundation of the whole thing is the writing by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows. They didn't just write a story about gamblers; they built a specific, heightened world based on the short stories of Damon Runyon.

The Runyonesque Language Trap

If you’re looking at a Guys and Dolls script for the first time, the dialogue feels weird. It’s formal but low-brow. Characters rarely use contractions. Instead of saying "I don't know," a character might say, "I do not know." This isn't an accident. Damon Runyon, the guy who wrote the original stories like The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown, created this specific dialect. It’s called "Runyonesque."

It creates this bizarre, hilarious contrast. You have these underworld characters—muggers, bookies, and professional gamblers—speaking with the grammatical precision of a college professor, yet they’re talking about "scratched horses" and "floating craps games." When you’re reading the script, you have to lean into that. If a director or an actor tries to make the lines sound "natural," the whole thing falls apart. The artifice is the point.

Why the Plot Structure is Actually Genius

Modern musicals often struggle with the "book"—the stuff between the songs. Often, the plot feels like a flimsy excuse to get to the next dance number. Not here.

The Guys and Dolls script is built on a double-arc structure that is perfectly balanced. You have the "comic" couple, Nathan Detroit and Adelaide, who have been engaged for 14 years. Then you have the "romantic" couple, Sky Masterson and Sarah Brown. One couple is fighting the inevitability of marriage, while the other is fighting an impossible attraction.

Look at the "Save-a-Soul" Mission plotline. It’s not just a backdrop. It provides the ticking clock. Nathan needs a place for his game. The Mission needs "sinners" to stay open. Sky makes a bet that forces these two worlds to collide. It’s a mechanical marvel of screenwriting (or playwriting, in this case). Every character’s motivation is tied to a specific, tangible goal. Nathan needs $1,000. Sarah needs souls. Sky needs to win a bet to keep his reputation.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Eddie Money Take Me Home Tonight Lyrics Still Hit Different Decades Later

The Nathan Detroit Dilemma

There’s a massive debate among theater nerds about how to play Nathan Detroit. If you read the original Guys and Dolls script, Nathan isn't a "lead" in the traditional sense. He doesn't even have a real solo song until the 1992 revival added "Sue Me" as a more prominent moment (though it was always there, it’s often what people remember most).

In the text, Nathan is a ball of anxiety. He’s a guy who’s been dodging a wedding ring for over a decade while trying to outrun the police. When Sinatra played him in the film, he brought too much "cool." Nathan shouldn't be cool. He should be sweating. He’s the guy who knows everyone but owns nothing. Reading his lines, you see the desperation. "I have been running this crap game since I was a juvenile delinquent." That’s not a boast; it’s a tired fact of life.

The 1992 Revival vs. The Original

If you’re sourcing a script for a production, you’ll likely run into the 1992 version, which starred Nathan Lane and Faith Prince. This version is often considered the "gold standard" for modern audiences. Why? Because it tweaked the pacing.

The original 1950s text has some dated moments, sure. But the 1992 revisions (and subsequent London revivals like the 2023 immersive show at the Bridge Theatre) prove that the bones of the Guys and Dolls script are indestructible. The 2023 Nicholas Hytner production in London actually messed with the staging—putting the audience in the middle of the street—but they didn't have to change much of the dialogue. Why? Because the rhythm of the lines dictates the movement. You can't speak a Burrows line and stand still. The words have an inherent "hustle" to them.

Misconceptions About Sarah Brown

A lot of people think Sarah Brown is a "boring" character. The "straight man" to Sky’s gambler. But if you read the Havana scene in the script, you see the depth. Sarah isn't just a prude; she’s someone who is deeply lonely and has used her faith as a shield. When that shield drops, she’s more impulsive than Sky is.

Sky Masterson, on the other hand, is the one who undergoes the biggest change. He starts the script as a man who believes everything has a price and a probability. By the end, he’s betting his entire future on a roll of the dice in a sewer. It’s poetic, in a gritty, New York sort of way.

Technical Elements for Performers

If you are an actor working from the Guys and Dolls script, pay attention to the stage directions. They are surprisingly sparse. This is a "talky" show. The comedy comes from the "beats"—the silences between the fast-paced chatter.

👉 See also: The Ethel Cain For Sure Cover: Why This 10-Minute Slowburn is Still Trapped in Our Heads

Take the song "Adelaide’s Lament." The lyrics are written into the script as a medical report. It’s a brilliant piece of character development. We learn more about Adelaide’s 14-year frustration through her psychosomatic cold than we would from a ten-minute monologue. It’s "show, don't tell" at its finest.

What Really Happened with the Script's Authorship?

There's a bit of drama behind the scenes. Jo Swerling wrote an initial version of the script, but the producers didn't think it captured the Runyon "flavor" well enough. They brought in Abe Burrows, a radio comedy writer. Burrows basically rewrote the whole thing.

The problem? Swerling had a contract. So, to this day, the credits usually read "Book by Jo Swerling and Abe Burrows." But if you ask musical theater historians, they’ll tell you: the "voice" you hear—the snap, the crackle, the New York wit—is almost entirely Burrows. He was later blacklisted during the McCarthy era, which adds a layer of irony to a show that is often seen as "wholesome" Americana.

Actionable Steps for Studying the Script

If you are a director, actor, or just a fan of the theater, here is how you should approach the text to get the most out of it:

- Read the original Damon Runyon stories first. Specifically The Idyll of Miss Sarah Brown and Blood Pressure. It helps you understand the DNA of the characters before the music was ever added.

- Audit the contractions. Go through your lines and mark every place where you'd normally use a contraction (don't, can't, won't) and see how the script uses the full words. Practice saying them without sounding like a robot. The trick is to speak them fast, not stiffly.

- Map the "Bets." Almost every scene in the first act is a negotiation or a wager. Identify what each character is "betting" in every conversation. It’s rarely just about money; it’s about status.

- Listen to the 1950 Original Cast Recording. While the 1992 version is fun, the 1950 recording features Robert Alda and Vivian Blaine. Their delivery is closer to the original intent of the Burrows script—a bit sharper and less "caricature."

- Focus on the "Small" Characters. The script gives incredible lines to characters like Nicely-Nicely Johnson and Benny Southstreet. They aren't just comic relief; they are the "Greek Chorus" of Broadway. Their dialogue sets the stakes for Nathan's world.

The Guys and Dolls script remains a staple because it doesn't try to be "important." It tries to be funny, and in doing so, it captures something very real about human nature—our tendency to gamble on things we can't control, like love and luck. Whether you're analyzing it for a class or preparing for an audition, treat the text like a musical score. The notes are right there in the punctuation.

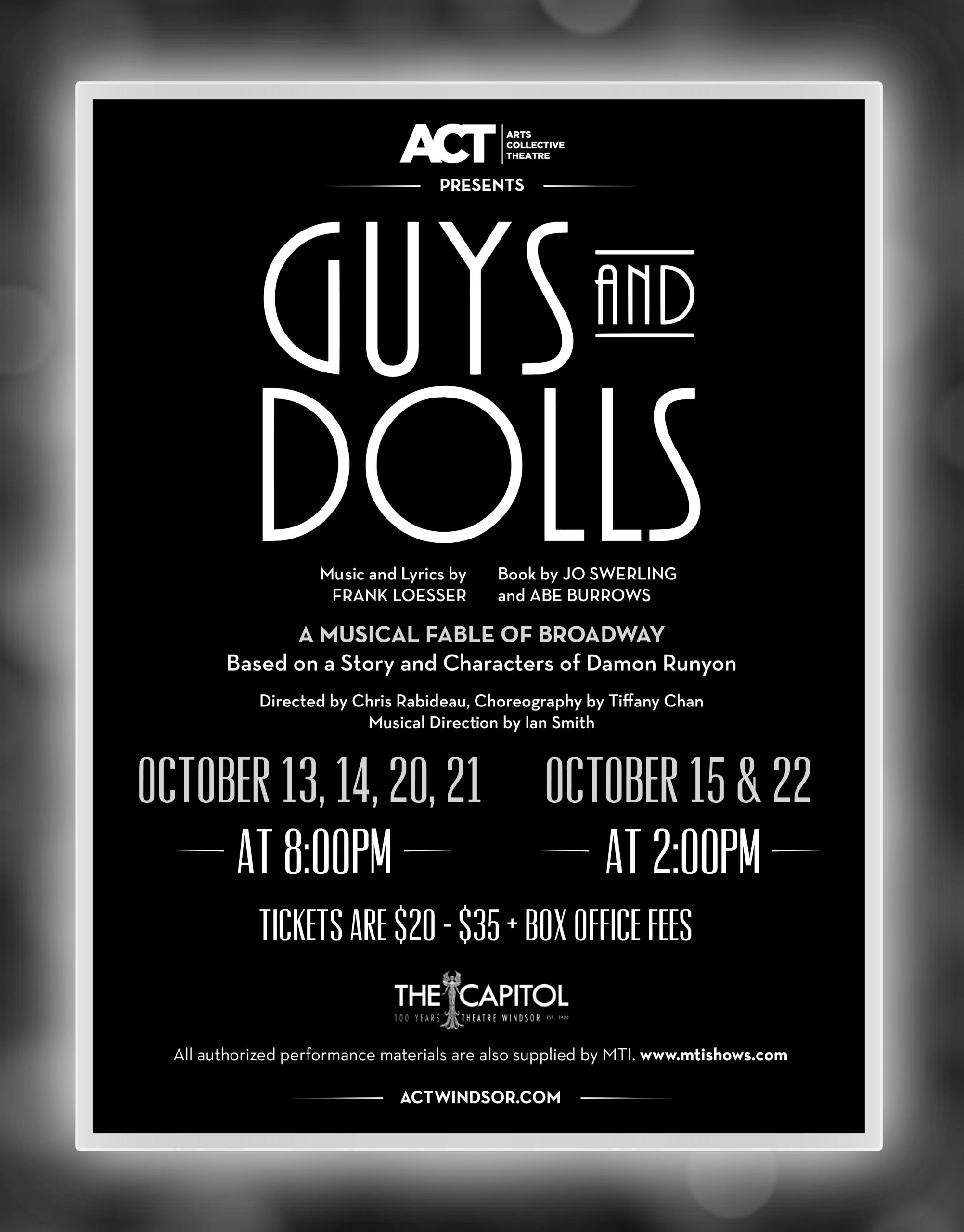

Check the licensing through Music Theatre International (MTI) if you're planning a production. They hold the rights and provide the official libretto, which includes all the latest stage notes and standard dialogue used in professional revivals. Don't rely on unofficial transcripts; the specific wording is where the comedy lives.