You’ve probably touched a dozen of them today without even realizing it. They’re in your credit cards, your passport, that sticker on the bottom of your new frying pan, and maybe even under your dog’s skin. Radio frequency identification chips—or RFID for short—are basically the quietest tech revolution in history. It’s not like the iPhone launch where everyone was screaming in the streets. This was a slow, steady takeover of how we track physical objects.

People freak out about them sometimes. You've heard the rumors. People think they're being tracked by satellites or that a chip the size of a grain of rice is recording their every move. Honestly? That's just not how the physics works.

How these little things actually work (minus the jargon)

Most radio frequency identification chips don't have batteries. They’re "passive." Imagine a tiny antenna and a speck of silicon. When a reader—like the gate at a library or a handheld scanner in a warehouse—sends out a radio wave, the chip catches a tiny bit of that energy. It uses that "stolen" power to wake up for a fraction of a second and scream back a serial number. That’s it. It’s like a digital reflection in a mirror.

If there's no reader nearby, the chip is dead. It’s cold. It’s doing absolutely nothing.

💡 You might also like: The Largest Train in the World: What Most People Get Wrong

Now, "active" RFID is a different beast. Those have batteries. They can broadcast a signal hundreds of feet. You’ll see these in those E-ZPass transponders on car windshields or tracking multi-million dollar shipping containers across a port. They’re bigger, pricier, and way more powerful. But for 99% of the stuff you encounter, you’re dealing with the passive ones that cost about five to ten cents to manufacture.

Frequency matters more than you think

Not all chips are created equal. You’ve got Low Frequency (LF), which is what’s in your pet’s microchip. It’s slow and you have to be practically touching it to read it. Then there’s High Frequency (HF), which powers NFC—the tech that lets you tap your phone to pay for a latte. Finally, there’s Ultra-High Frequency (UHF). This is the retail king. It’s what companies like Walmart and Zara use to count 500 shirts in five seconds.

Why Walmart is obsessed with them

Back in the early 2000s, Walmart tried to force all its suppliers to use radio frequency identification chips. It was kind of a disaster. The tech was too expensive, the readers were glitchy, and everyone hated the mandate. But fast forward to now, and they’ve doubled down. Why? Because losing track of inventory is a multi-billion dollar headache.

In a traditional warehouse, a guy has to walk around with a barcode scanner and physically "see" every label. It’s slow. It sucks. With RFID, you just walk through an aisle with a wand and it "hears" every item in the boxes. You get 99% inventory accuracy compared to maybe 65% with manual counting.

Delta Air Lines did something similar with luggage. They started embedding radio frequency identification chips into baggage tags. Instead of a ground crew member having to scan every suitcase by hand—which they often skip because they're in a rush—the belt itself tracks the bag. It reduced mishandled bags by a massive margin because the system knows exactly where a suitcase is at every handoff point.

🔗 Read more: J. Robert Oppenheimer: What Most People Get Wrong About the Father of the Atom Bomb

The privacy elephant in the room

Let's be real: the idea of "tagging" everything is creepy to some people. There’s a legitimate concern about "skimming." This is where someone with a high-powered reader walks past you and tries to grab your credit card info or passport data.

Is it possible? Yeah, technically.

Is it happening at scale? Not really. Most modern cards use encryption. Even if a hacker "hears" the chip, they get a one-time code that’s useless for a second transaction. Plus, the range for these chips is tiny. Someone would have to be uncomfortably close to your back pocket to get a read. That’s why those "RFID-blocking wallets" are mostly a marketing gimmick. They work, but you probably don't need one unless you're hanging out in very specific, high-tech thief dens.

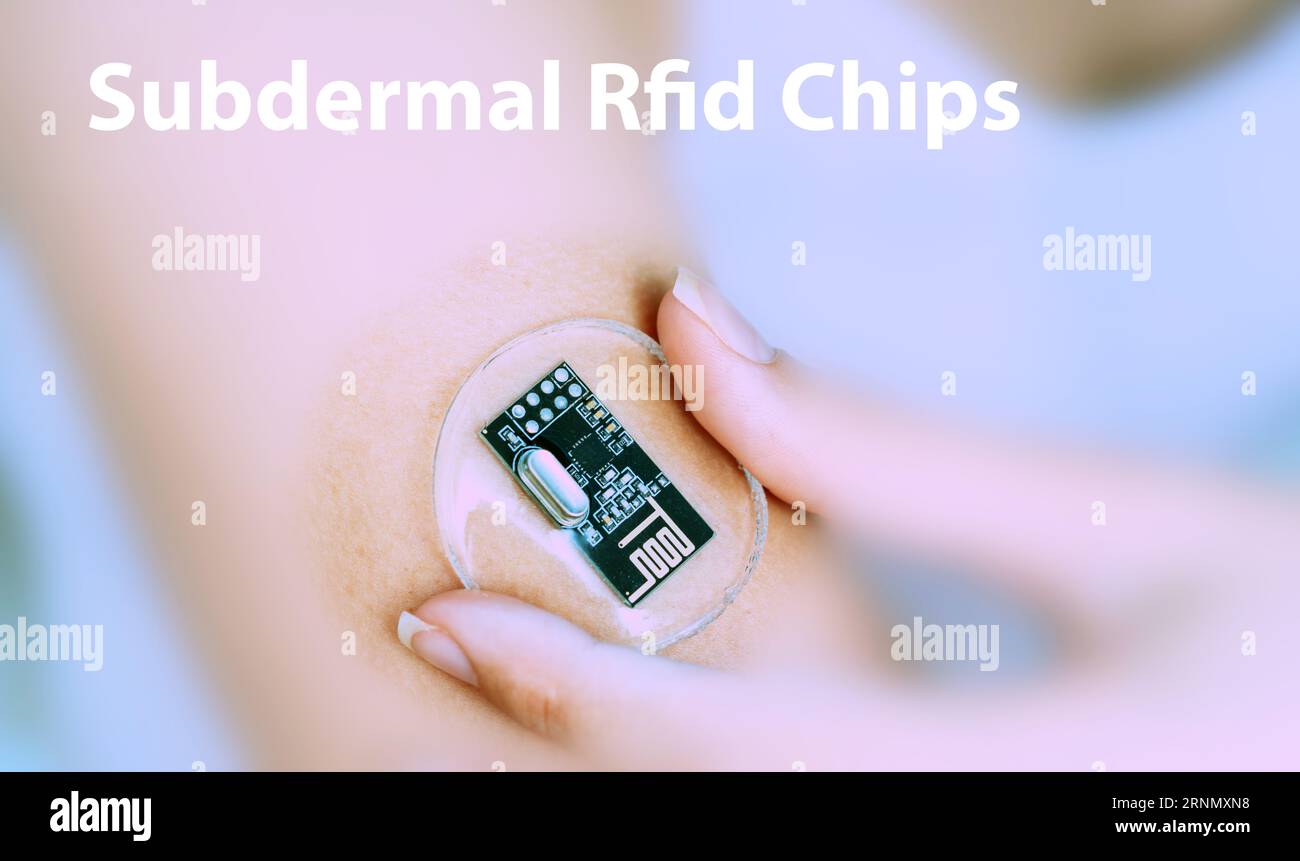

The "Microchipping Humans" debate

Then there's the biohacking crowd. Companies like Three Square Market in Wisconsin made headlines a few years ago for offering to chip their employees. It was totally voluntary. The employees used the chip in their hand to open doors or buy snacks at the breakroom kiosk.

It sounds like sci-fi, but it's basically just a permanent key fob. The medical community has been doing this for years with pacemakers and insulin pumps, though those are way more complex than a simple ID chip. The real debate isn't about the tech itself—it's about who owns the data and whether an employer should ever have that kind of "access" to a human body.

Where the tech is failing (or just being weird)

Metal and water are the sworn enemies of radio frequency identification chips. Radio waves hate them. If you put a standard RFID tag on a soda can or a bottle of water, the signal gets absorbed or bounced around like crazy. Engineers have had to invent "on-metal" tags that use a special spacer to keep the antenna from touching the conductive surface. It’s clunky and makes the tags more expensive.

There’s also the "garbage" problem. We’re putting millions of these tiny silicon chips and aluminum antennas into disposable packaging. When you throw away a clothing tag with a chip in it, it goes to a landfill. While a single chip is tiny, the sheer volume is starting to worry environmentalists. We’re basically sprinkling electronic waste across the planet one t-shirt at a time.

✨ Don't miss: Why You Should Merge Two Images Into One PDF (and How to Do It Right)

Misconceptions that just won't die

- "They can track me via GPS." Nope. Not even close. GPS requires a massive amount of power and a clear line of sight to satellites. A passive RFID chip has neither. Your phone tracks you; your sweater’s RFID tag does not.

- "They can be read from miles away." Maybe a high-powered active tag with a huge battery could reach a mile, but your credit card's range is about two inches.

- "They’ll die in the microwave." Actually, this one is true. If you microwave an RFID chip, the metal antenna will arc and the chip will fry. Please don't microwave your passport to "protect your privacy." You'll just ruin a very expensive document.

What’s coming next?

We’re moving toward something called "The Internet of Every Thing." Not just "Things" like your fridge, but everything.

Imagine a grocery store with no checkout lines. You just walk out with a cart and the sensors at the door read every radio frequency identification chip in your bag and charge your account automatically. Amazon Go uses cameras for this, but RFID is a much cheaper way to do it for big-box stores.

We’re also seeing "printed" electronics. Instead of a silicon chip, researchers are working on conductive inks that can be printed directly onto paper or plastic. This could bring the cost of a tag down to a fraction of a penny. At that point, even a banana could have a digital identity.

Actionable steps for the real world

If you're a business owner or just someone curious about the tech, here is how you should actually handle RFID right now:

- Check your inventory pain points. If you’re a small retailer losing 10% of your stock to "clerical errors," a basic UHF RFID system might pay for itself in six months. Don't go overboard; start with your highest-value items.

- Audit your privacy settings. You don't need an RFID-blocking bag, but you should check which of your cards have the "contactless" symbol (the little radio wave icon). If you're paranoid, just keep those cards sandwiched between other credit cards in your wallet; the metal in the other cards acts as a natural shield.

- Watch the labels. Next time you buy clothes at a major chain, look at the hangtag. If it’s thick and has a weird rectangular shape inside it, that’s an RFID chip. You can usually just peel it off and throw it away once you get home if it bugs you.

- Don't overcomplicate the "Biohacking" stuff. If you're thinking about getting a chip implant for convenience, remember that tech standards change. A chip put in today might be using an obsolete frequency in ten years, and then you've got a useless piece of glass in your hand. Stick to wearable tech for now.

The reality of radio frequency identification chips is a lot more boring—and a lot more useful—than the conspiracy theories suggest. It’s just a way to give physical objects a digital voice. It’s about making sure the milk is fresh, the blood bags in hospitals are tracked, and your Amazon package actually shows up at your door. It’s not a spy movie; it’s just a very organized filing cabinet that uses radio waves instead of paper.