He stood in the New Mexico desert, squinting against a light that shouldn't have existed. It was July 16, 1945. The world was about to change, and Julius Robert Oppenheimer was the man who had pulled the trigger. We call him the father of the atom bomb, a title that carries both the weight of scientific triumph and the shadow of unimaginable destruction.

But who was he, really?

Oppenheimer wasn't some lone genius working in a basement. He was a chain-smoking, poetry-quoting physicist who managed to herd a group of the world's most temperamental egos into a secret city called Los Alamos. Honestly, the fact that the Manhattan Project even worked is a miracle of logistics as much as physics. Most people think of the bomb as a singular invention, like the lightbulb. It wasn't. It was an industrial pivot that turned the United States into a factory of the apocalypse.

👉 See also: How Many People Died in the Challenger Explosion: The Seven Lives and a Legacy of Failure

The Making of a Theoretical Giant

Oppenheimer wasn't born a warrior. Far from it. He was a wealthy kid from New York City, a "Ethical Culture" school graduate who loved minerals and French literature. By the time he hit his twenties, he was bouncing around Europe, the epicenter of the quantum mechanics revolution. He studied under Max Born at Göttingen. He crossed paths with Heisenberg. He was brilliant, sure, but he was also erratic. At one point, he allegedly tried to poison his tutor with an apple laced with chemicals. Intense? Yeah, just a bit.

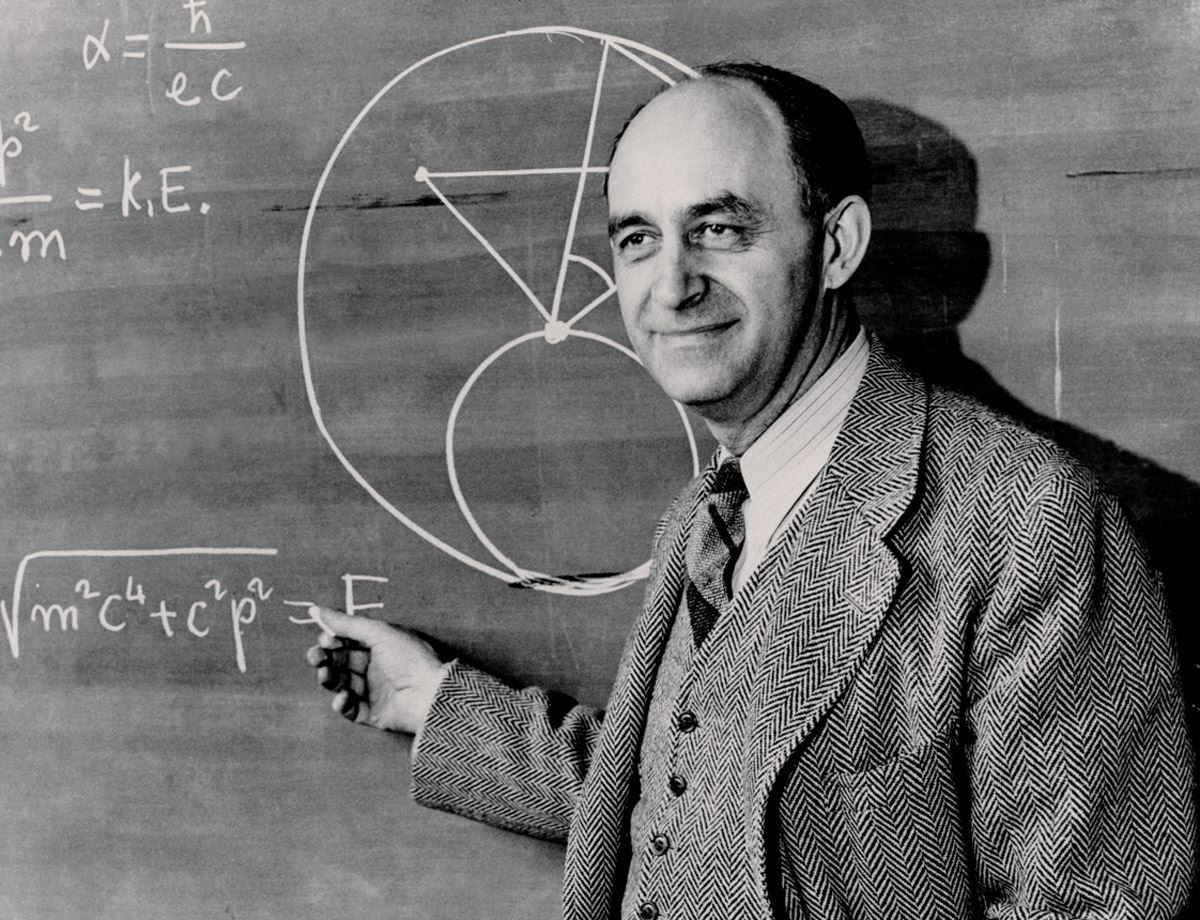

When he returned to the States, he basically built the theoretical physics program at Berkeley from scratch. He was the guy who introduced American students to the weird, counterintuitive world of the subatomic. He wasn't just teaching math; he was teaching a new way to see reality. His students imitated his mannerisms, his walk, even his cough. He had that kind of gravity.

Then came the letter from Einstein and Leo Szilard to FDR. The Nazis were potentially working on nuclear fission. The fear was real, cold, and immediate. The U.S. government needed a leader for the scientific side of the secret project to build a counter-weapon. General Leslie Groves—a no-nonsense military man who built the Pentagon—picked Oppenheimer. It was a weird choice. Oppenheimer had no administrative experience and a file full of "leftist" associations. But Groves saw something in him: a burning ambition.

Los Alamos and the Gadget

The Manhattan Project was a sprawling beast, stretching from the enrichment plants in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to the reactors in Hanford, Washington. But the brain was Los Alamos. As the father of the atom bomb, Oppenheimer had to convince Nobel Prize winners to move their families to a dusty mesa in the middle of nowhere.

Life at Los Alamos was bizarre. It was a high-pressure cooker of brilliant minds, barbed wire, and secrecy. They called the bomb "the gadget." They weren't just "building a weapon"; they were solving the most complex physics puzzle in human history.

How do you compress a core of plutonium fast enough to trigger a chain reaction before the whole thing just blows itself apart in a "fizzle"?

That was the "implosion" problem. It required precision that barely existed in the 1940s. Oppenheimer was everywhere. He coordinated the chemists, the metallurgists, and the theoretical teams. He was down to about 115 pounds, living on coffee and cigarettes. He was vibrating with the stress of it.

The Trinity Test: "I Am Become Death"

The culmination of his work happened at the Trinity site. When the plutonium device—the "Fat Man" design—detonated, it produced a flash that could be seen for hundreds of miles. The heat was so intense it turned the desert sand into a green glass we now call Trinitite.

In that moment, Oppenheimer reportedly thought of a line from the Bhagavad Gita: "Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds."

It’s a haunting quote. It suggests a man who knew exactly what he had unleashed. While some scientists at Los Alamos were cheering, others were silent. Some were already signing petitions to stop the bomb from being used on civilian targets. Oppenheimer didn't sign them. He believed the weapon had to be demonstrated to the world to ensure it was never used again after the war.

What Most People Get Wrong About His "Regret"

There is this popular narrative that Oppenheimer spent the rest of his life as a broken, repentant man. It’s more complicated than that. He never said he regretted building the bomb. He believed it was a technical necessity to end the war. What he regretted was the lack of international control over nuclear energy that followed.

He became a victim of the very machine he helped build. In the 1950s, during the height of the Red Scare, his security clearance was revoked. The government he served turned on him, using his old associations with communists to paint him as a risk. It was a public humiliation. The father of the atom bomb was effectively cast out of the kingdom he created.

Edward Teller, the man who wanted to build the even more powerful Hydrogen Bomb (the "Super"), testified against him. The scientific community was split down the middle. For Oppenheimer, the "fatherhood" of the bomb became a crown of thorns. He spent his final years at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, a shell of his former self, still smoking, still quoting poetry, but distant.

Why the Legacy Matters in 2026

We live in a world defined by the "Oppenheimer moment." Today, as we grapple with Artificial Intelligence and biotechnologies that could rewrite our DNA, the story of the Manhattan Project is more relevant than ever. It's the ultimate example of "can we" vs. "should we."

Oppenheimer's life proves that science doesn't happen in a vacuum. It is deeply, messily political. He wasn't a saint, and he wasn't a villain. He was a man who saw a mathematical possibility and turned it into a physical reality, only to realize that reality was bigger than he could control.

Actionable Insights for the Modern Reader

If you want to truly understand the impact of the father of the atom bomb, don't just watch the movies. Look at the primary sources and the long-term geopolitical shifts his work caused.

- Study the Franck Report: Read the 1945 document where scientists actually warned the government about the nuclear arms race before the bomb was even dropped. It shows that the ethical debate was happening in real-time.

- Explore the "Dual-Use" Dilemma: Research how nuclear technology led to both the threat of annihilation and the promise of carbon-free energy. This same dilemma applies to AI today.

- Visit the Sites (If You Can): The Bradbury Science Museum in Los Alamos or the National Museum of Nuclear Science & History in Albuquerque offer a visceral look at the scale of the engineering.

- Evaluate Expert Authority: When looking at modern "fathers" of tech (like the creators of LLMs), use the Oppenheimer framework. Ask: Are they considering the social "fallout" of their work, or are they just focused on the technical "sweetness" of the problem?

Oppenheimer once said that "physicists have known sin." He meant that they had lost their innocence. They had moved from the blackboard to the battlefield. Understanding his journey isn't just a history lesson; it's a warning about the responsibility of being right. The father of the atom bomb didn't just give us a weapon; he gave us a mirror to look at our own capacity for both genius and destruction.