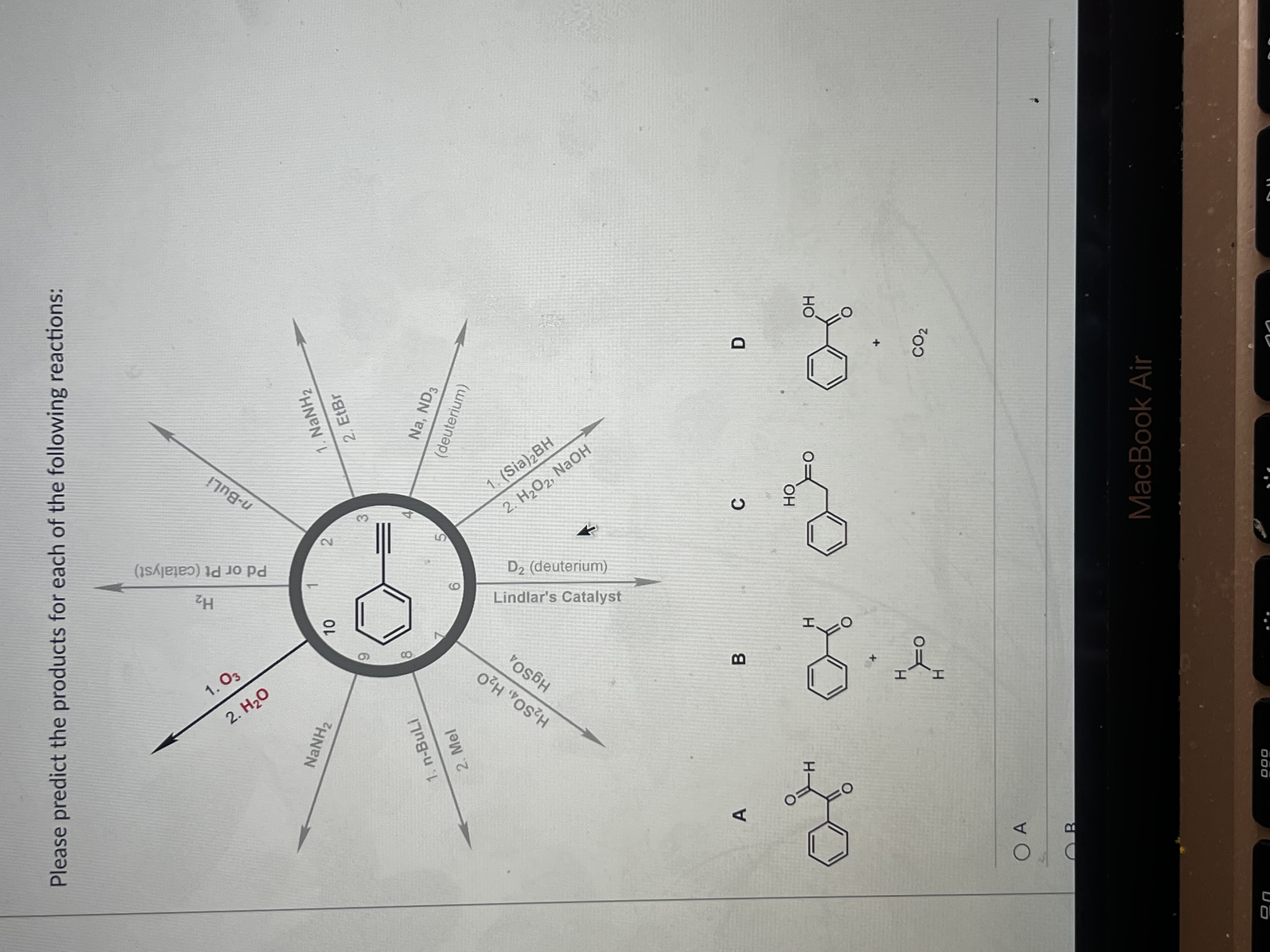

Chemistry isn't just a list of rules. It’s more like a puzzle where half the pieces are invisible until you shine the right light on them. When a professor or a lab manual asks you to predict the products for each of the following reactions, it feels like being handed a map in a language you only half-speak. You recognize the letters, sure. You know what a carbon looks like. But how does that "C" interact with a "Br" when there’s heat involved?

Most students—and even some seasoned researchers—hit a wall because they try to memorize every single outcome. That’s a losing game. There are millions of possible organic reactions. Instead of memorizing, you have to learn to see the electronic "hunger" in a molecule.

Why Carbon Just Wants to Be Stable

At the heart of every reaction is a search for peace. Molecules are chaotic. They have high-energy spots called functional groups that are basically itching to change. When you look at a prompt to predict the products for each of the following reactions, your first job is to find the "hot spots."

Is there a double bond? That’s a cloud of electrons just waiting to grab something positive. Is there a halogen like Chlorine or Bromine? That’s a "leaving group" packing its bags, ready to exit as soon as a better partner comes along. If you can identify the nucleophile (the giver) and the electrophile (the taker), you've already solved 80% of the problem.

Honestly, it’s mostly about electrostatic attraction. Opposites really do attract in the flask. If you see a negatively charged Oxygen (a methoxide ion, perhaps), and a carbon attached to a bulky Bromine, something is going to happen. The Oxygen is going to attack. The Bromine is going to leave.

The Nucleophile vs. Electrophile Dance

You’ve got to get comfortable with the vocabulary. A nucleophile is "nucleus-loving." It has extra electrons, maybe a full negative charge or just a lonely pair of electrons sitting there. Think of it as the aggressor. The electrophile is "electron-loving." It’s often a carbon that feels a bit "naked" because it's attached to an electronegative atom that’s hogging all the electron density.

When you're asked to predict the products for each of the following reactions, start by drawing the partial charges. Put a $\delta+$ on the carbon and a $\delta-$ on the halogen. This simple visual cue makes the "attack" path obvious. It’s like drawing a target on the molecule.

The Big Four: Substitution and Elimination

If you’re staring at an alkyl halide, you’re almost certainly looking at one of four pathways: $S_N1, S_N2, E1,$ or $E2$. This is where most people get tripped up. They look at the reagents and freeze.

But look closer at the environment.

✨ Don't miss: Finding a mac os x 10.11 el capitan download that actually works in 2026

$S_N2$ is the "backside attack." It’s fast. It’s clean. It happens in one step. If you see a primary carbon (a carbon attached to only one other carbon) and a strong, small nucleophile like $OH^-$ or $CN^-$, bet on $S_N2$. The nucleophile hits the carbon from the opposite side of the leaving group, and—pop—the leaving group flies off. The geometry even inverts, like an umbrella blowing inside out in the wind.

Now, contrast that with $S_N1$. This is the "lazy" reaction. It happens in two steps. First, the leaving group just falls off on its own. This leaves behind a carbocation—a positively charged carbon. This only works if that carbon is "tertiary" (connected to three other carbons) because those neighbors help stabilize the positive charge. Once the carbocation is formed, the nucleophile just wanders over and attaches.

What About the E-Reactions?

Elimination is the rival of substitution. Instead of replacing the leaving group, the molecule decides to kick it out and form a double bond (an alkene). This usually happens when you use a base instead of a nucleophile.

Wait, what’s the difference?

A nucleophile wants a carbon. A base wants a hydrogen.

If you see a big, bulky, "fat" base like Potassium tert-butoxide (t-BuOK), it’s too large to squeeze in and hit a carbon. It’s like a giant trying to walk through a narrow door. Instead, it just grabs a hydrogen from the outside of the molecule. This forced "grab" causes the leaving group to exit, creating a double bond. That’s an $E2$ reaction. When you predict the products for each of the following reactions involving t-BuOK, you should almost always be drawing an alkene, specifically the "Hoffman" product (the less substituted double bond).

Addition Reactions: Breaking the Double Bond

Alkenes are different beasts. They don't have leaving groups. Instead, they have that rich $\pi$-bond (the second line in the double bond). To predict the products for each of the following reactions involving alkenes, you need to think about Markovnikov’s Rule.

Vladimir Markovnikov was a Russian chemist who noticed a pattern in the 1860s. He realized that when you add something like $HBr$ to a double bond, the Hydrogen always goes to the carbon that already has more Hydrogens.

🔗 Read more: Examples of an Apple ID: What Most People Get Wrong

"The rich get richer."

It sounds unfair, but it’s just physics. Adding the Hydrogen to the less-substituted side creates a more stable carbocation on the more-substituted side. If you’re predicting a reaction between propene and $HCl$, the Chlorine is going to end up on the middle carbon. Every. Single. Time. (Unless you add peroxides, but that’s a whole different radical mechanism).

The Nuance of Stereochemistry

Sometimes, knowing where the atoms go isn't enough. You have to know their 3D orientation. Are they "syn" (on the same side) or "anti" (on opposite sides)?

Take bromination. If you add $Br_2$ to a cyclohexane ring, the two Bromines won't be on the same side. They'll be trans to each other. This is because they form a "bromonium ion" bridge that blocks one side of the molecule, forcing the second Bromine to attack from the bottom. If you don't draw those wedges and dashes correctly, you haven't truly predicted the product.

Carbonyl Chemistry: The Real Heavyweight

As you move further into organic chemistry, the $C=O$ bond becomes the center of the universe. Aldehydes, ketones, esters, carboxylic acids—they all revolve around the fact that the Carbonyl Carbon is extremely electrophilic.

The Oxygen is an electron hog. It pulls density away from the Carbon, leaving it "thirsty" for electrons.

When you predict the products for each of the following reactions involving a carbonyl, look for Grignard reagents ($RMgBr$) or hydrides ($LiAlH_4$). These are high-energy "nucleophile bombs." They slam into that Carbonyl Carbon, breaking the $C=O$ double bond and turning it into a single bond with an Oxygen (which eventually becomes an alcohol after you add water).

Esters and the "Leaving Group" Surprise

Esters ($R-COOR'$) are tricky. Beginners often think they behave like ketones. They don't. Because an ester has an $-OR$ group, it has a potential leaving group. If you hit an ester with a strong nucleophile, it won't just add once; it might add twice, kicking out the $-OR$ group in the process.

💡 You might also like: AR-15: What Most People Get Wrong About What AR Stands For

This is why predicting products requires you to look at the stoichiometry. Did the prompt say "1 equivalent" or "excess"? If it’s excess, that molecule is going to get shredded and rebuilt.

A Step-by-Step Checklist for Predicting Products

When you're staring at a blank page with five different chemical equations, don't panic. Follow this mental flowchart.

- Identify the Functional Groups: Is it an alcohol? An alkene? An acyl chloride?

- Classify the Reagents: Is this a strong acid? A weak base? A powerful reducing agent like $NaBH_4$?

- Determine the Mechanism: Is this going to be an addition, a substitution, an elimination, or a rearrangement?

- Check for Stability: If a carbocation forms, can it rearrange? (Hydride or methyl shifts are the "gotchas" of organic chemistry).

- Draw the Intermediate: Don't skip this. If you draw the intermediate, the product becomes inevitable.

- Account for Stereochemistry: Use wedges and dashes. Check for chiral centers. Is it a racemic mixture?

Real-World Example: The Friedel-Crafts Trap

Imagine you have benzene and you add propyl chloride ($CH_3CH_2CH_2Cl$) with $AlCl_3$. You might think the product is propylbenzene.

It’s not.

The intermediate is a primary carbocation, which is unstable. It immediately undergoes a "hydride shift" to become a secondary carbocation. The actual product is isopropylbenzene (cumene). If you want to accurately predict the products for each of the following reactions, you have to watch out for these internal molecular "shuffles." Molecules are shifty. They want to be in the lowest energy state possible.

Moving Forward with Confidence

Predicting reaction products is a skill that scales. Once you master the basics of electron flow (arrow pushing), you can start looking at complex natural product synthesis or pharmaceutical development. The rules don't change; the molecules just get bigger.

To get better, you need to stop looking at the answer key so quickly. Spend ten minutes struggling with a single reaction. Trace the electrons. If you get it wrong, don't just erase it—figure out why your path was higher energy than the correct one.

Next Steps for Mastery:

- Practice Arrow Pushing: Grab a blank notebook and draw the mechanisms for the top 20 "named" reactions (Aldol, Claisen, Wittig).

- Study pKa Values: Knowing which proton is the most acidic tells you exactly where a base will strike first.

- Use 3D Models: If you can’t visualize a backside attack, buy a cheap plastic molecular model kit. Feeling the "steric hindrance" in your hands makes it real.

Understanding these patterns turns a stressful exam into a logical exercise. You aren't guessing anymore. You’re calculating. Chemistry is predictable, provided you know what the atoms are searching for. They just want stability. Help them find it.