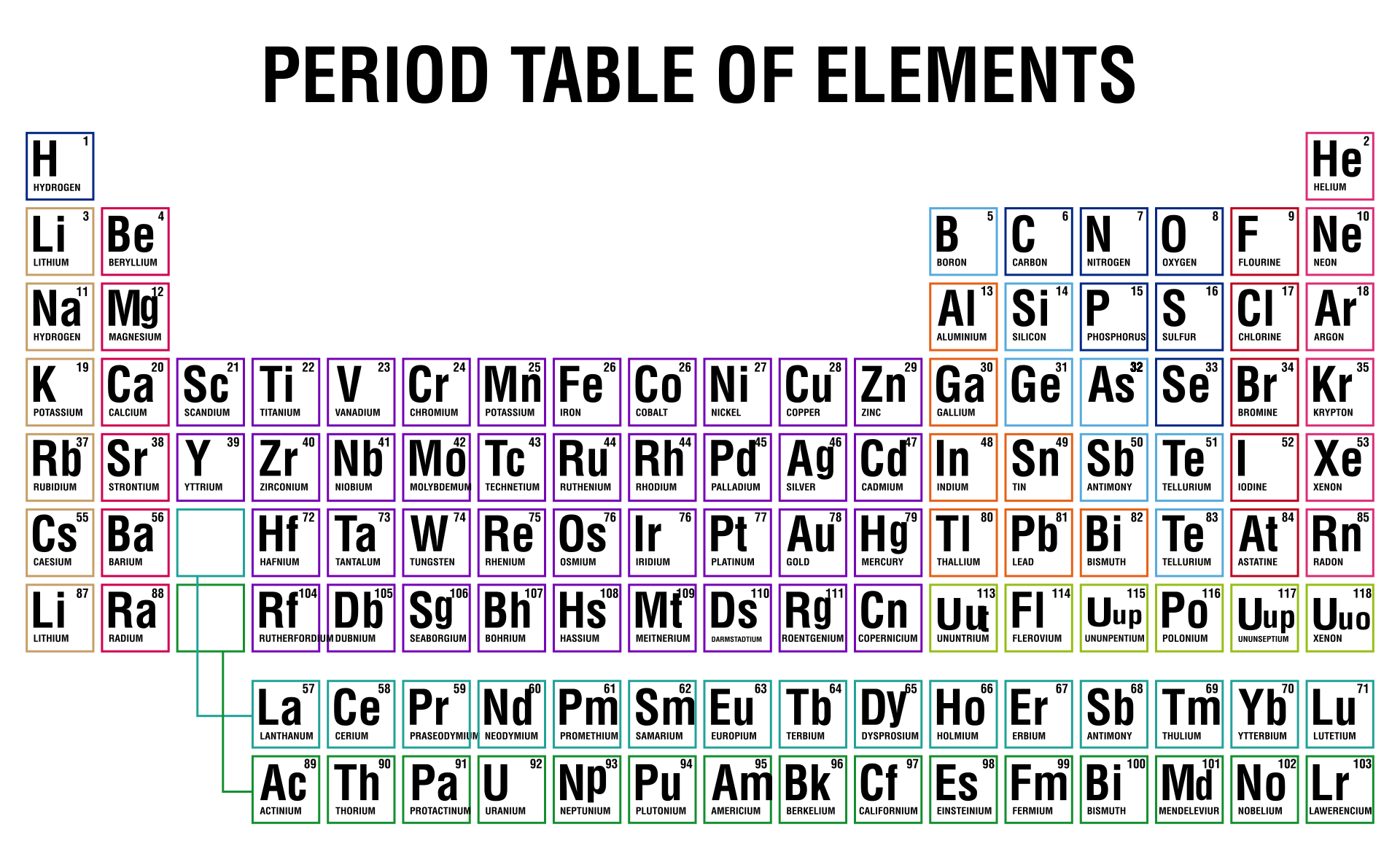

You're staring at a poster of the periodic table, and honestly, it looks like a giant, colorful Tetris board that someone gave up on. But look closer at those little numbers in the corners—specifically the ones with a plus or minus sign. Those are periodic table ion charges, and they are basically the social media status of every element in the known universe. Some elements are desperate to give away their electrons like they're junk mail, while others are aggressive hoarders, snatching up every negative charge they can find. If you’ve ever wondered why your salt doesn't explode when you put it on your fries, or why your phone battery actually holds a charge, it all comes down to these tiny electrical imbalances.

Everything wants to be stable. It’s the universal law of "chilling out." For an atom, being stable means having a full outer shell of electrons, usually eight. This is the Octet Rule, and it’s the primary driver behind why atoms transform into ions. Think of an atom like a person trying to fit into a specific social circle. If they have one extra electron that's making them awkward and unstable, they’ll literally throw it at someone else just to reach that sweet spot of chemical zen.

The Drama of Groups 1 and 2

Let’s talk about the "givers." Over on the far left side of the table, you’ve got the Group 1 elements: Hydrogen, Lithium, Sodium, and the rest of the gang. These guys have exactly one electron in their outermost shell. They hate it. It's like having a single annoying roommate you want to kick out so you can have the apartment to yourself. Because they lose one negatively charged electron, they end up with a +1 charge.

Sodium (Na) is the classic example here. In its neutral state, it’s a soft metal that’s so reactive it’ll literally catch fire if it touches water. But once it loses that pesky electron and becomes $Na^{+}$, it becomes half of the salt on your table. It’s a total personality 180. Group 2—the Alkaline Earth Metals like Magnesium and Calcium—takes it a step further. They have two extra electrons. They ditch both, resulting in a +2 charge. It takes a bit more energy to kick two roommates out than one, but for Magnesium, the payoff of stability is worth the effort.

Why Non-Metals Are Such Hoarders

Now, flip your gaze to the right side of the table. Here, the vibe changes completely. We’re moving away from the generous metals and into the territory of the electronegative non-metals. These elements are "close but no cigar" to having a full shell. Fluorine and Chlorine (Group 17, the Halogens) have seven electrons. They are desperate. They only need one more to hit that magic number eight.

🔗 Read more: Why a 9 digit zip lookup actually saves you money (and headaches)

Instead of giving anything away, they aggressively pull electrons from passing atoms. This is why periodic table ion charges for Halogens are almost always -1. They gain a negative particle, so they become negative themselves. It’s simple math, really. Oxygen and Sulfur in Group 16 need two more electrons, so they typically form -2 charges.

The Noble Gas Ghosting

Then you have the Noble Gases in Group 18. Helium, Neon, Argon... they’re the elite. They have full outer shells already. They don't want your electrons, and they certainly aren't giving theirs away. Their charge? Zero. They are chemically inert because they’ve already won the game of atomic stability. They don't react because they don't have to. It's a lonely existence at the top, but it's very stable.

The Messy Middle: Transition Metal Chaos

This is where things get genuinely weird. If you look at the middle block of the table—the Transition Metals like Iron, Copper, and Gold—the neat "count the columns" trick stops working. These elements are the rebels. They have "d-orbitals," which is basically a fancy way of saying they have extra storage space for electrons that doesn't follow the standard 8-electron rule.

- Iron (Fe) can be $Fe^{2+}$ or $Fe^{3+}$. It depends on its mood (and the chemical environment).

- Copper (Cu) fluctuates between $+1$ and $+2$.

- Gold (Au) is famously stubborn but can show up as $+1$ or $+3$.

Why does this happen? Because these atoms are large and complex enough that they can lose electrons from different "layers" of their structure without falling apart. This is why we use Roman numerals when naming them, like Iron(III) Chloride. Without that numeral, you’re just guessing, and in chemistry, guessing is a great way to melt a beaker you weren't supposed to melt.

💡 You might also like: Why the time on Fitbit is wrong and how to actually fix it

The Energy Price Tag: Ionization and Affinity

You can't just move electrons around for free. There’s a tax. Scientists call the energy required to remove an electron Ionization Energy. Elements on the left (metals) have low ionization energy; they’re practically giving electrons away for free. Elements on the top right have incredibly high ionization energy. Trying to take an electron from Fluorine is like trying to take a steak from a grizzly bear. You’re going to have a bad time.

On the flip side, we have Electron Affinity, which is how much an atom "wants" a new electron. The Halogens have massive electron affinity. They release a burst of energy when they finally snag that missing piece. This tug-of-war between "I want to keep mine" and "I want yours" is what creates every chemical bond that keeps your body from dissolving into a puddle of carbon dust.

Common Misconceptions About Charge

A big mistake people make is thinking that an ion charge is a permanent, physical tattoo on the atom. It’s not. An atom is only an ion when it’s in a specific environment, like being dissolved in water or bonded to another element. In a solid chunk of pure Aluminum, the atoms aren't necessarily sitting there with a +3 charge; they're sharing a "sea" of electrons in a metallic bond.

Another weird one? The idea that all ions are single atoms. You’ve actually got polyatomic ions. These are groups of atoms—like Nitrate ($NO_{3}^{-}$) or Sulfate ($SO_{4}^{2-}$)—that act as a single unit with a collective charge. They’re like a little gang of atoms that decided to share their burdens and their electrical imbalances together. If you're calculating periodic table ion charges for a complex reaction, you have to treat these clusters as one single entity.

📖 Related: Why Backgrounds Blue and Black are Taking Over Our Digital Screens

How to Predict Charges Without a Cheat Sheet

If you’re stuck in a lab (or a test) and don't have a labeled chart, just look at the Group number.

- Group 1: $+1$ (always).

- Group 2: $+2$ (always).

- Group 13: Mostly $+3$ (like Aluminum).

- Group 15: $-3$ (usually).

- Group 16: $-2$ (usually).

- Group 17: $-1$ (almost always).

Skip Group 14 (Carbon’s group). They’re the fence-sitters. Carbon has four electrons, which is exactly half of eight. It’s just as hard to gain four as it is to lose four, so Carbon usually just decides to share electrons through covalent bonding rather than becoming an ion. It’s the "middle child" of the periodic table—doing its own thing and refusing to conform to the +/- labels.

Real-World Stakes: Why This Actually Matters

This isn't just academic fluff. The reason Lithium-ion batteries are in your pocket right now is specifically because Lithium is so good at moving its $+1$ charge around. When you charge your phone, you’re forcing Lithium ions to one side of the battery. When you use your phone, they migrate back, releasing that stored electrical energy. If Lithium had a different ion charge, your phone might be the size of a microwave or die in ten minutes.

In your body, the balance of $Na^{+}$, $K^{+}$, and $Ca^{2+}$ is what allows your nerves to fire. Every time you think a thought or twitch a finger, it's because your cells are pumping these ions across membranes. If your periodic table ion charges get out of whack—say, through extreme dehydration—your heart can literally stop beating because the electrical signals can't travel through the "short circuit" of your imbalanced cells.

Your Next Steps for Mastering Ions

Knowing the charges is only half the battle; the real skill is seeing how they fit together.

- Practice the "Criss-Cross" Method: If you have Aluminum ($+3$) and Oxygen ($-2$), the charges have to balance to zero. You’ll need two Aluminums ($+6$ total) and three Oxygens ($-6$ total) to make $Al_{2}O_{3}$.

- Memorize the "Big Five" Polyatomics: Ammonium ($NH_{4}^{+}$), Nitrate ($NO_{3}^{-}$), Carbonate ($CO_{3}^{2-}$), Sulfate ($SO_{4}^{2-}$), and Phosphate ($PO_{4}^{3-}$). These show up in 90% of basic chemistry problems.

- Check the Solubility: Just because two ions can bond doesn't mean they'll stay together in water. Some ions are so attracted to water molecules that they’ll let go of their partners the second things get wet.

Start by looking at the ingredients on the back of a Gatorade bottle or a box of crackers. You’ll see names like "Calcium Carbonate" or "Sodium Phosphate." Now that you know the hidden logic of the periodic table, those aren't just scary-sounding chemicals anymore—they're just predictable pairs of atoms that found a way to balance their charges and get stable.