Seymour "Swede" Levov is the guy you were supposed to be. In the opening pages of Philip Roth’s American Pastoral, we meet a man who is essentially a walking, breathing monument to the post-war American ideal. He’s a legendary high school athlete, a Marine, and the heir to a thriving Newark glove factory. He marries a former Miss New Jersey. He buys a stone house in the pastoral paradise of Old Rimrock. He does everything "right."

Then his daughter blows up a post office.

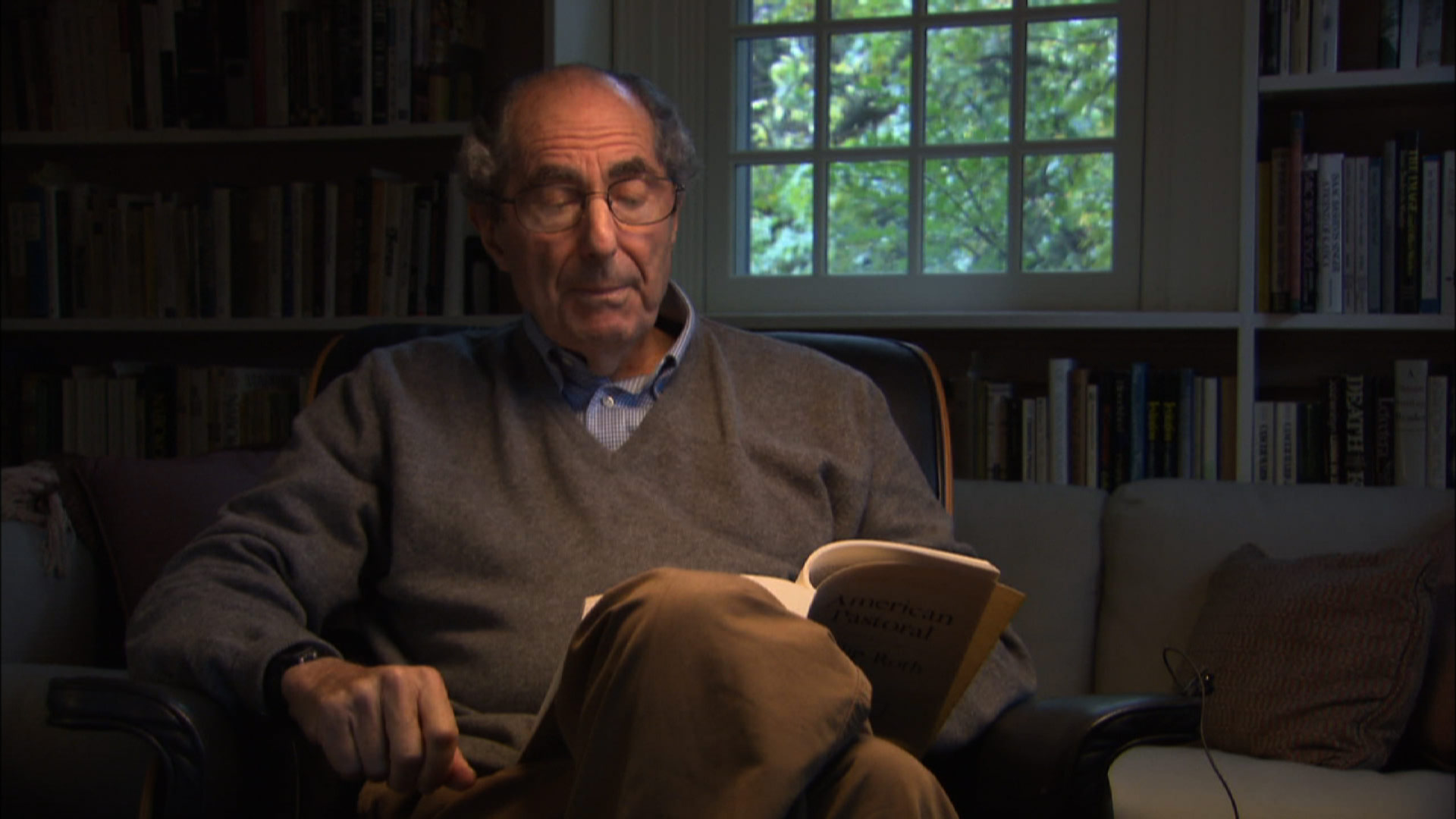

It’s a brutal, messy, and deeply uncomfortable premise. When Roth published this in 1997, he wasn't just writing a story about a family falling apart; he was conducting an autopsy on the American psyche. You’ve likely heard it’s a "Great American Novel," but honestly, that label is almost too polite for what this book actually does. It's a 400-page scream. It’s about the exact moment the 1950s dream of order collided with the chaotic, screaming reality of the 1960s.

The Myth of the Swede and the Reality of Philip Roth

Roth uses his frequent alter-ego, Nathan Zuckerman, to narrate the Swede’s downfall. This is a crucial detail because it reminds us that we are looking at the Swede through a lens of nostalgia and projection. Zuckerman sees the Swede at a high school reunion and is shocked to find the "god" of his childhood looking... normal. But the story underneath is anything but.

The Swede is a man who believes in the "pastoral"—this idea of a peaceful, rural, ordered life where hard work equals safety. He represents the Jewish-American journey of assimilation. His father, Lou Levov, built a business with grit and sweat, and the Swede is the polished result of that labor. He thinks he can outrun history. He thinks if he’s kind enough, successful enough, and "American" enough, the world will leave him alone.

He was wrong.

👉 See also: Christopher McDonald in Lemonade Mouth: Why This Villain Still Works

History isn't something you can opt out of. For the Levovs, history arrived in the form of their daughter, Merry. She’s the stuttering girl who grows up to be a domestic terrorist. Why? Roth doesn't give you a simple "it was the bad crowd" answer. He suggests that Merry is the byproduct of the very perfection the Swede tried to maintain. She is the "rimrock" cracking open.

Why American Pastoral Hits Differently in 2026

Reading Philip Roth's American Pastoral today feels eerily prophetic. We live in an era of intense polarization, where the "American Dream" feels more like a debated historical artifact than a shared goal. Roth captured that specific vibration of a society losing its collective mind.

The book explores "the indigenous American berserk." That’s Roth’s term for the chaotic, violent undercurrent of American life that periodically bubbles to the surface.

- The Glove Factory: This isn't just a setting. Roth spends pages—sometimes dozens of them—describing the minute details of glove making. It’s about craft. It’s about a world where things were made by hand, where labor had a tangible result.

- The Riot: The 1967 Newark riots serve as the backdrop for the beginning of the end. The factory, once a symbol of progress, becomes a fortress in a war zone.

- The Stutter: Merry’s stutter is a physical manifestation of her inability to fit into the "perfect" narrative her parents created for her. It’s her rebellion before she ever picks up a bomb.

Critics like Michiko Kakutani and Harold Bloom have long hailed the book for its linguistic density. Roth doesn't write "easy" sentences. He writes sentences that spiral and loop, reflecting the frantic internal monologue of a father trying to figure out where he went wrong. It's a psychological thriller where the monster is just... time and change.

The Problem With "Doing Everything Right"

Most people think of the American Dream as a ladder. You climb, you get to the top, you stay there. Philip Roth argues that the ladder is actually a tightrope over a canyon of chaos.

✨ Don't miss: Christian Bale as Bruce Wayne: Why His Performance Still Holds Up in 2026

The Swede’s tragedy isn't that he was a bad man. He was a good man. That’s what makes the book so devastating. If he had been a jerk, or an abusive father, or a corrupt businessman, we could say he deserved his fate. But he was generous, loyal, and hardworking. Roth is telling us that being a "good American" provides zero protection against the randomness of the world.

There’s a scene where Lou Levov, the patriarch, visits the Swede's home and criticizes everything from the grass to the choice of a shiksa wife. It’s a masterclass in intergenerational tension. Lou represents the old world—struggle, survival, and skepticism. The Swede represents the new world—comfort, acceptance, and a dangerous level of optimism.

Understanding the "Indigenous American Berserk"

When Merry bombs the general store, killing a local doctor, the "pastoral" is dead. The rest of the novel is essentially the Swede wandering through the wreckage of his life, trying to find a reason.

He meets Rita Cohen, a radical who claims to know Merry, and the encounters are some of the most surreal and unsettling in modern literature. Rita is the antithesis of everything the Swede stands for. She’s crude, chaotic, and hates his middle-class sensibilities. Through her, Roth forces the reader to look at the Swede not as a hero, but as a "bourgeois" relic who is blind to the injustices around him.

Is the Swede blind? Or is he just trying to survive? Roth doesn't take sides, which is why the book remains a staple in university seminars. It forces you to sit in the discomfort of not having an answer.

🔗 Read more: Chris Robinson and The Bold and the Beautiful: What Really Happened to Jack Hamilton

Key Themes to Track

- Identity and Performance: Everyone is playing a role. The Swede plays the athlete; Dawn plays the beauty queen; Merry plays the revolutionary.

- The Fall of Newark: The city’s decline mirrors the family’s decline. It’s a literal and metaphorical crumbling of the foundations.

- Parental Guilt: This is perhaps the most relatable part. The agonizing "What did I do?" that haunts any parent when a child goes astray.

How to Approach the Text Without Getting Lost

If you’re picking up American Pastoral for the first time, don't expect a fast-paced plot. It’s a slow burn. Roth will take you on long tangents about the history of leather tanning or the nuances of Miss America pageants. Stick with it. Those details aren't filler; they are the "stuff" of the world that is being destroyed.

The prose is thick. It’s chewy. Sometimes a single sentence will span half a page. But there’s a rhythm to it. It’s meant to feel like a fever dream. When you get to the dinner party scene at the end of the book—widely considered one of the greatest sequences in 20th-century fiction—you’ll realize how all those small details have been tightening the noose.

The dinner party is a masterpiece of subtext. While the characters discuss mundane things, the Swede is losing his mind, realizing that everyone at the table has secrets, and his "pastoral" life was always an illusion.

Actionable Ways to Engage with the Novel

- Listen to the Audiobook: Ron Silver’s narration is legendary. He captures the Jersey accent and the frantic energy of Roth’s prose perfectly.

- Research the 1967 Newark Riots: Understanding the historical context makes the Swede’s desperation to save his factory much more poignant.

- Compare with the Film: Honestly? The 2016 movie directed by Ewan McGregor is... fine. But it misses the internal rot that makes the book great. Watch it only after you’ve read the book to see how difficult it is to translate Roth's internal monologues to the screen.

- Read the "Trilogy": American Pastoral is the first in Roth’s "American Trilogy," followed by I Married a Communist and The Human Stain. Reading all three gives you a massive, panoramic view of the American century.

Philip Roth's American Pastoral isn't a comfortable read. It’s not a book you read to feel good about the world. You read it to understand the fragility of the structures we build around ourselves. It’s a reminder that no matter how much we want to live in a "pastoral," the "berserk" is always just outside the door, waiting for its turn.

If you want to truly understand the tension between the "Greatest Generation" and the counterculture that followed, there is no better roadmap. It’s a heavy, brilliant, and ultimately heartbreaking look at what happens when the American Dream finally wakes up.

To get the most out of your reading, start by mapping the timeline of the Levov family against major US historical events from 1945 to 1975. You'll notice that every personal tragedy in the Swede's life corresponds almost exactly with a moment of national upheaval. This reveals Roth's ultimate trick: he didn't write a family drama; he wrote a biography of the United States disguised as one.