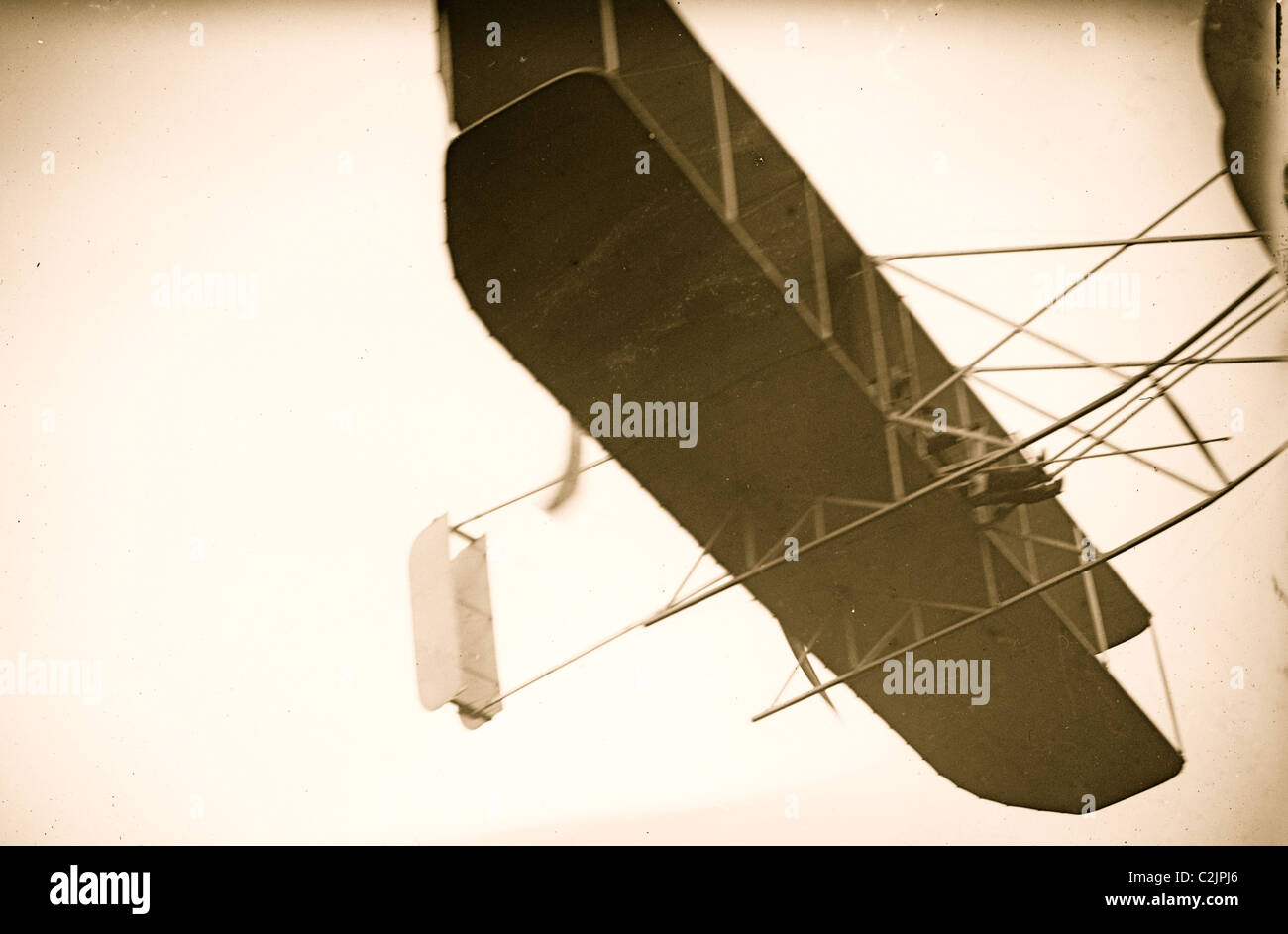

You’ve seen it. Everyone has. That grainy, black-and-white shot of a spindly wooden contraption hovering just a few feet off the North Carolina sand while a man in a dark suit runs alongside it. It’s arguably the most famous photo in the history of technology. But here’s the thing about Orville Wright airplane pictures: they weren't just lucky snapshots taken by a passerby. They were the result of a calculated, almost obsessive obsession with documentation that nearly failed because the "photographer" had never even seen a camera before that morning.

Honestly, the story of how we got these images is almost as chaotic as the first flight itself.

The Lifesaver Who Almost Missed the Shot

Imagine being John T. Daniels. You’re a member of the Kill Devil Hills Life-Saving Station. Your day usually involves pulling shipwrecked sailors out of the Atlantic. Then, two brothers from Ohio—who've been playing with giant kites in your backyard for three years—hand you a Korona-V view camera.

Orville set the whole thing up. He was meticulous. He didn't just point and pray; he positioned the tripod, focused the lens on the exact patch of air where he hoped the machine would lift off, and then handed Daniels a rubber squeeze bulb.

The instructions were basic: "Squeeze the bulb if anything interesting happens."

When the 1903 Flyer actually rose, Daniels was so floored by the sight of a 600-pound machine defying gravity that he nearly forgot his one job. He later admitted he wasn't even sure if he’d actually triggered the shutter until the brothers developed the glass plate weeks later in their Dayton darkroom. Talk about high-stakes photography. If he’d blinked, the Wrights might have been remembered as just another pair of eccentric dreamers with no proof.

Why These Pictures Look Different

If you look closely at some of the original Orville Wright airplane pictures, you’ll notice weird dark splotches or "scarring" on the edges. That isn't some vintage filter. It’s actual battle damage from the Great Dayton Flood of 1913.

The Wrights kept their glass plate negatives in a shed behind their home. When the levee broke and the city went underwater, those priceless records were submerged in mud and water for days. Orville eventually cleaned them, but the water left its mark. It’s a miracle they survived at all.

🔗 Read more: How Do You Erase Messages on Facebook Without Leaving a Trace

The Science of the Selfie (1900s Style)

The Wrights didn't take pictures because they wanted to be famous. They were scientists. Photography was their data log.

They used 5x7 inch glass plates, which was the high-def of 1903. While most people in the early 1900s were taking stiff family portraits, Orville and Wilbur were capturing:

- Wing-warping mechanisms in mid-flex.

- The exact angle of the "canard" (the front elevator) during a stall.

- The embarrassing "plow-ins" where the Flyer ate sand.

They were even recording the "Smeaton coefficient"—basically air pressure math—and using photos to verify if their wind tunnel data matched real-world physics. Orville was so intense about it that he kept a notebook for every exposure, listing the f-stop, the time of day, and even the type of plate used.

Not Just the Flyer

While the 1903 first-flight photo gets all the glory, the collection at the Library of Congress (which Orville’s estate donated in 1949) has over 300 negatives.

✨ Don't miss: iPhone 17 Pro Max Camera Specs: Why the 48MP Triple-Threat Actually Matters

It’s not all airplanes. You get these raw, honest glimpses into their camp life. There’s a picture of their kitchen at Kitty Hawk with cans of food lined up on shelves. There’s one of Wilbur looking exhausted. These Orville Wright airplane pictures sort of humanize the legends. They weren't just "The Wright Brothers"; they were two guys living in a shack, fighting mosquitoes, and eating canned beans while trying to solve a problem that had stumped humanity since Da Vinci.

The First "Action Shot" from the Air

Fast forward a few years to 1910. The Wrights had moved their testing to Huffman Prairie, a cow pasture outside Dayton. By now, they weren't just taking pictures of planes; they were taking them from planes.

Orville took a kid named William Preston Mayfield up in a Wright Model B. Mayfield was only 13 or so at the time (sources vary slightly on his exact age, but he was a "rookie" for the Dayton Daily News). He held his camera over the side and snapped the first still photo ever taken from an airplane in flight.

Think about that. In seven years, they went from "maybe we can fly" to "let's take a teenager up and start the aerial photography industry."

How to Spot a "Fake" or Mislabeled Wright Photo

Because the Wrights were so successful, a lot of people tried to claim they were first. This led to a huge legal fight with the Smithsonian that lasted decades. Orville was so annoyed that he actually sent the 1903 Flyer to a museum in London for years just to spite the Americans who wouldn't admit he was first.

When you’re looking for authentic Orville Wright airplane pictures, keep these things in mind:

- The Pilot's Position: In the 1903 shot, the pilot is lying flat on his stomach. If the pilot is sitting up, it’s a later model (like the 1908 or 1910 versions).

- The Location: If you see sand and dunes, it’s Kitty Hawk/Kill Devil Hills. If you see grass and cows, it’s Huffman Prairie.

- The Propellers: The original Flyer had two "pusher" propellers behind the wings.

What We Can Learn From Orville's Lens

The Wrights taught us that if you’re going to do something world-changing, you better document it. Without those glass plates, their claims would have been dismissed as tall tales from the Outer Banks.

If you want to dive deeper into these archives, the Library of Congress has digitized the entire collection. You can zoom in so far you can see the grain in the wood of the propellers. It’s a rabbit hole worth falling down.

💡 You might also like: Triple X Celeste Leaked: Why Digital Security Fails Online Creators

Actionable Insights for History Buffs:

- Visit the Source: If you're in D.C., the National Air and Space Museum has the original 1903 Flyer. Seeing the actual textures from the photos in 3D is a trip.

- Search the Prints and Photographs Division: Use the Library of Congress online search for "Wright Brothers Negatives." Look for the ones with "flood damage"—they usually have the most interesting backstories.

- Check the "First Flight" Annotations: The Smithsonian has an annotated version of the 1903 photo that points out the footprints in the sand and the bench used to prop up the wing. It changes how you see the "void" in the image.

The Wrights didn't just invent the airplane; they invented the way we remember the invention. They knew that a picture wasn't just worth a thousand words—it was worth a thousand patents. And honestly? They were right.