Most of us have seen them. Those stark, incredibly sharp images of a grey, cratered world hanging in a void so black it looks like ink. You’ve probably scrolled past dozens of NASA pictures of the moon on Instagram or seen them blown up on massive museum walls. But there is a weird disconnect between what we see and what is actually there. We’ve been staring at the lunar surface through NASA’s lenses for over sixty years, yet most people still think the moon is a glowing white marble. It’s not. It’s actually about the color of a worn-out asphalt driveway.

The reason those photos look the way they do isn't just because of "space magic." It’s a mix of brutal physics, early cold war engineering, and some very clever digital stitching that happens back on Earth. When you look at an image from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) or a grainier shot from the 1960s Lunar Orbiter program, you aren’t just looking at a "snapshot." You’re looking at a data map.

The Grey Deception and the Albedo Problem

Why does the moon look so bright in NASA photos? It's all about albedo. This is basically just a fancy word for how much light a surface reflects. The moon has a very low albedo—around 0.12. This means it only reflects about 12% of the light that hits it. For context, Earth reflects about 30%. If you put a piece of the moon next to a fresh asphalt road, they’d almost match.

NASA photographers and digital imaging experts have to deal with the fact that there is no atmosphere to scatter light. On Earth, the air softens shadows. On the moon, shadows are absolute. They are pitch black. If you’re standing in a crater’s shadow, you are in total darkness, even if the sun is blazing right above the rim. This creates a nightmare for cameras. To get those crisp NASA pictures of the moon where you can see the texture of the regolith (the moon dust), the exposure has to be cranked way up. This makes the moon look like a glowing lantern, but it’s really just a dark rock caught in a very bright spotlight.

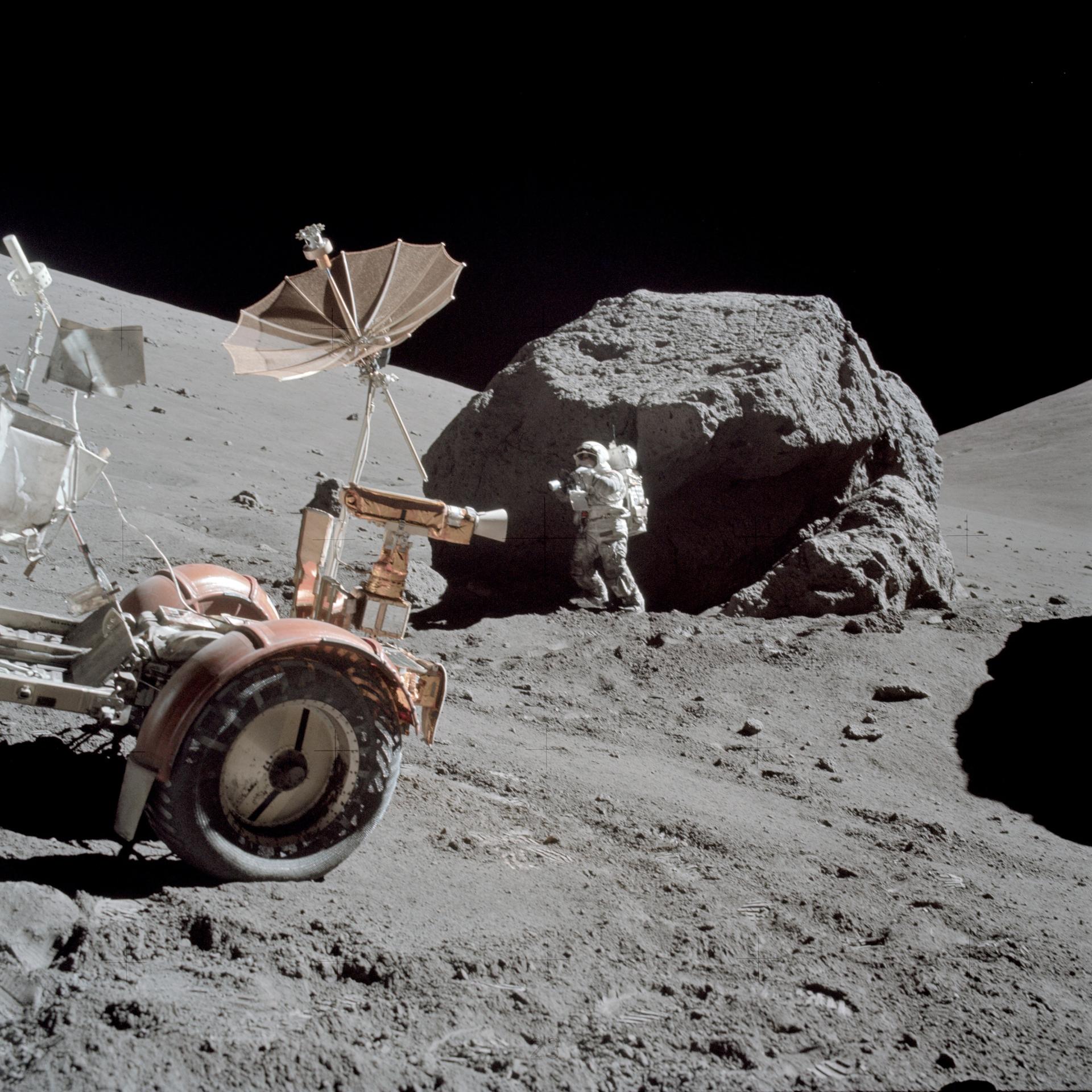

Those Iconic Hasselblad Shots

We have to talk about the Apollo missions. Between 1969 and 1972, astronauts carried modified Hasselblad 500EL cameras. These weren't your standard off-the-shelf units. They used 70mm film, which is massive compared to the 35mm film your grandpa used. This is why Apollo-era NASA pictures of the moon are so insanely detailed even by today's standards. You can blow them up to the size of a billboard and still see the individual footprints left by Buzz Aldrin.

There’s a specific photo, AS11-40-5903. You know the one. It’s Buzz Aldrin standing on the lunar surface, and you can see Neil Armstrong and the Eagle lander reflected in his gold visor. It’s arguably the most famous photo in human history. But look closer. The horizon is curved because the moon is small. The ground is uneven. It looks staged to conspiracy theorists because the lighting is "too perfect." In reality, the lunar soil is retroreflective. It reflects light back toward the source, much like a bike reflector or a stop sign. This is why the area directly around an astronaut’s shadow often looks brighter than the rest of the ground—a phenomenon called the Heiligenschein effect.

🔗 Read more: The Truth About How to Get Into Private TikToks Without Getting Banned

Modern Lunar Imaging: More Than Just Snapshots

Nowadays, we aren't relying on film dropped back to Earth in a canister. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has been circling the moon since 2009. It carries the LROC—a suite of three cameras. Two are Narrow Angle Cameras (NACs) that provide high-resolution black-and-white images, and one is a Wide Angle Camera (WAC).

The detail is terrifyingly good. We can see the rover tracks from the 1970s. We can see the "descent stages" of the lunar modules left behind. But these modern NASA pictures of the moon are processed differently. Since the LRO is moving at thousands of miles per hour, it uses "push-broom" imaging. It captures one line of pixels at a time and stitches them together. If you’ve ever tried to take a panorama on your phone while someone was walking through it, you know how weird that can look. NASA’s software experts at the Goddard Space Flight Center have to mathematically correct for the orbiter's jitter, the moon's rotation, and the changing angle of the sun.

The Mystery of the "Far Side"

People love to call it the "Dark Side," but that’s wrong. It gets just as much sun as the side we see. It’s just the "Far Side" because the moon is tidally locked to Earth. For a long time, we had no idea what it looked like. The first time we saw it was in 1959 via the Soviet Luna 3 mission, but NASA's later images revealed something shocking: it looks nothing like the front.

The side facing us is covered in "maria"—those dark, flat basaltic plains formed by ancient volcanic eruptions. The far side? It's almost entirely craters and highlands. It looks like a completely different planet. NASA pictures of the moon's far side show a rugged, battered landscape that acted as a shield for Earth, taking the brunt of asteroid impacts for billions of years.

Digital Artistry or Scientific Fact?

A common question people ask is: "Are the colors real?"

💡 You might also like: Why Doppler 12 Weather Radar Is Still the Backbone of Local Storm Tracking

Mostly, no. But they aren't "fake" either. Many NASA pictures of the moon use "false color." Scientists assign different colors to different wavelengths of light that the human eye can't see. For example, if you see a lunar map where the moon looks like a tie-dye shirt with splashes of blue and orange, you’re looking at titanium and iron concentrations.

- Blue areas are rich in titanium.

- Orange/Red areas are low in titanium and higher in iron.

- Bright white/pink usually indicates young craters where fresh rock has been kicked up.

This isn't done to make the pictures look pretty for posters. It’s done so geologists can "read" the moon from 240,000 miles away. They can tell exactly where to land a future mission to find specific minerals without ever touching the surface.

The Problem with "The Blue Marble"

One of the most breathtaking NASA pictures involving the moon isn't actually of the moon—it's Earthrise. Taken by William Anders during the Apollo 8 mission, it shows Earth peeking over the lunar horizon. This photo changed everything. It was the first time we saw our home as a fragile, lonely blue dot in a vacuum.

But here’s a secret: the photo was originally vertical. In the raw film, the moon is on the side. It was flipped horizontally for publication because humans find it easier to process a "horizon" that goes left-to-right. It’s a subtle bit of editing that shows how NASA frames the moon to help us relate to a landscape that is fundamentally alien.

How to Explore These Images Yourself

NASA doesn't hide this stuff. Actually, they’re pretty obsessed with sharing it. If you want to dive deeper than just a Google Image search, there are specific tools that let you play "lunar explorer" from your couch.

📖 Related: The Portable Monitor Extender for Laptop: Why Most People Choose the Wrong One

The LROC QuickMap is basically Google Earth but for the moon. You can zoom in so far that you can see individual boulders that have rolled down crater walls. It’s updated constantly with new data.

Then there’s the NASA Planetary Data System (PDS). This is where the raw, unwashed data lives. It’s not pretty. It’s huge files that require specialized software to open. But if you want to see exactly what the LRO saw before any public relations person touched it, that’s where you go.

What’s Next: The Artemis Era

We are currently entering a new golden age of lunar photography. The Artemis missions are going back, and this time, they’re bringing 4K, high-dynamic-range (HDR) cameras. We are going to see NASA pictures of the moon in colors and textures that make the Apollo photos look like charcoal sketches.

The goal now isn't just to prove we were there. It’s to map the "permanently shadowed regions" (PSRs) at the South Pole. These are spots where the sun hasn't shone in billions of years. NASA is using "shadow-cam" technology—cameras so sensitive they can see by the faint light reflected off nearby crater rims. They are looking for ice. And they’re finding it.

Practical Steps for High-Res Lunar Hunting

If you’re looking to find the best, most authentic imagery without the compression of social media, follow these steps:

- Visit the LROC Gallery: Go to the official Arizona State University LROC site. This is the primary source for modern lunar imagery. You can download "TIF" files that are several gigabytes in size.

- Check the Apollo Archive: Use the "Project Apollo Archive" on Flickr. It contains thousands of raw, unprocessed scans of the original flight film. It’s much more "real" than the polished versions you see in history books.

- Use NASA’s "Moon Trek": This is a web-based portal (part of NASA’s Solar System Treks) that allows you to fly over the lunar surface in 3D using real altimetry data.

- Look for the "Picture of the Day": The APOD (Astronomy Picture of the Day) often features lunar shots with detailed explanations from professional astronomers like Robert Nemiroff and Jerry Bonnell.

The moon is more than just a light in the sky. It’s a graveyard of solar system history, and NASA's photos are the only map we have to navigate it. Whether it's a grainy shot from 1966 or a multi-spectral map from 2026, these images are how we understand our place in the dark.

Stop looking at the moon as a flat white disc. Start looking at it as a world. A dark, dusty, titanium-rich world that we are just beginning to actually see clearly.