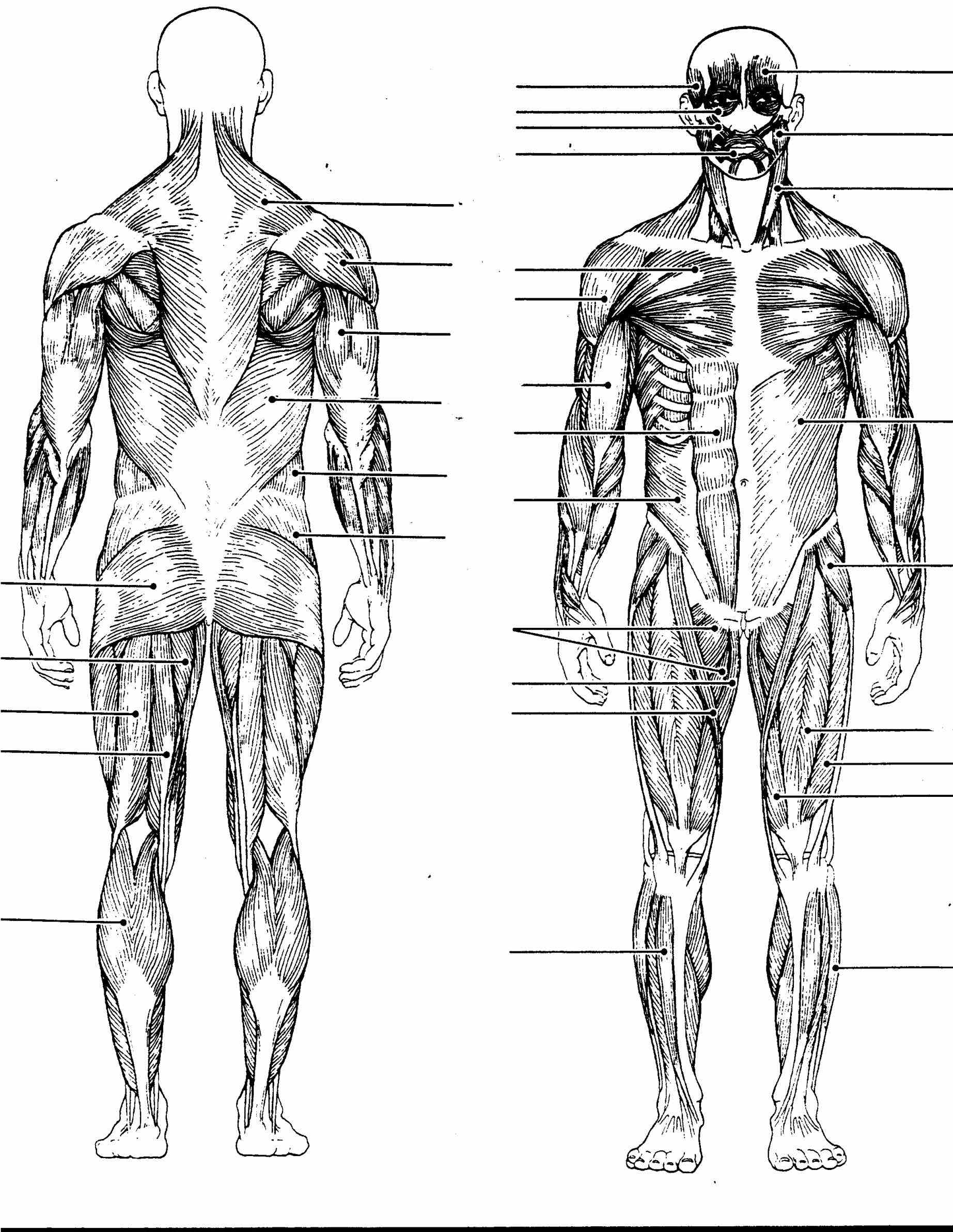

You’ve seen the posters in every doctor’s office. A red, flayed-looking figure staring blankly at the wall, covered in hundreds of tiny lines pointing to Latin names like latissimus dorsi or gastrocnemius. It looks organized. It looks complete. Honestly, though? Most muscles in the body diagram graphics you find online are lying to you by omission. They make the human body look like a collection of separate rubber bands. In reality, your anatomy is a messy, interconnected web of fascia and contractile tissue that doesn't actually stop where the diagram says it does.

If you’re trying to understand how you move, or why your lower back hurts when you’re actually just tight in the hamstrings, staring at a static 2D image only gets you halfway there. We have over 600 muscles. Some experts, like those at the Cleveland Clinic, argue the number is even higher depending on how you categorize certain muscle groups.

The Map is Not the Territory

A muscles in the body diagram is just a map. And just like a map of a city doesn't show you the traffic flow or the broken stoplights, a muscular diagram doesn't show you the tension.

Take the "core." Most people look at a diagram, point to the rectus abdominis—the six-pack—and think that's it. Wrong. Your core is a 3D canister. It involves the transverse abdominis (the deep stuff), the multifidus along your spine, and even your diaphragm. If you only train what you see on the front of the poster, you're setting yourself up for a world of hurt.

Movement is fluid. When you reach for a glass of water, your brain doesn't say, "Okay, biceps, contract now." It thinks about the goal. Your nervous system recruits "motor units" across multiple muscle groups. The diagram shows them in isolation, but they never work that way in real life.

Why Your Muscles in the Body Diagram Look Different Than Your Actual Body

Why does the guy on the poster look so shredded while we feel... well, normal? These diagrams usually strip away the subcutaneous fat and the fascia. Fascia is the real MVP here. It’s a collagenous connective tissue that wraps around every single muscle fiber. Think of it like the thin white skin on an orange segment.

Without fascia, your muscles would basically be a pile of jelly.

Researchers like Dr. Carla Stecco, a professor of anatomy and world-renowned fascia expert, have shown that this "stuffing" between muscles is actually a sensory organ. It has more nerve endings than the muscles themselves. So, when you look at a muscles in the body diagram, you’re missing the very thing that tells your brain where your limbs are in space. This is called proprioception.

The Big Players Everyone Skips

We all know the "glamour muscles." Biceps. Pecs. Quads. But the stuff that actually keeps you upright is often buried deep in the diagram.

👉 See also: Remedios caseros para tos seca nocturna: por qué tu garganta te odia al acostarte y cómo frenarlo

- The Psoas Major: This is the only muscle that connects your upper body to your lower body. It runs from your lumbar spine, through your pelvis, to your femur. If you sit at a desk all day, this muscle is constantly shortened. It’s a major culprit in "mysterious" back pain, yet on many diagrams, it’s hidden behind the intestines.

- The Serratus Anterior: These are the "finger-like" muscles on your ribs. Boxers love them. They stabilize your shoulder blade. If they’re weak, your shoulder blade "wings" out, and suddenly your bench press is trashed.

- The Popliteus: A tiny muscle behind your knee. Its only job? To "unlock" your knee so you can bend it. It’s small, but if it's angry, you aren't walking anywhere.

Variations in Human Design

Here is a wild fact: not everyone has the same muscles.

About 10% to 15% of people are missing the palmaris longus, a small muscle in the forearm. You can check right now. Touch your pinky to your thumb and flex your wrist. See that tendon popping up in the middle? No? You’re one of the "evolved" ones who doesn't have it. It’s basically a leftover from our tree-climbing ancestors.

The muscles in the body diagram usually shows a "standardized" human. But in the cadaver lab, things get weird. Some people have extra heads on their biceps. Others have muscles that attach slightly further down the bone, which—thanks to the laws of leverage—makes them naturally much stronger than someone with "standard" anatomy.

The Functional Chains: Why Isolation is a Myth

In the early 2000s, Thomas Myers published Anatomy Trains. It changed everything for physical therapists and athletes. He proposed that muscles don't just "end" at the bone. Instead, they are part of long functional lines.

The "Superficial Back Line" starts at the bottom of your toes, runs up your calves, hamstrings, and back, and ends at your eyebrows. This is why you can sometimes fix a tight neck by rolling a tennis ball under your foot. A standard muscles in the body diagram won't show you this connection. It treats the foot and the neck like they live in different ZIP codes.

They don't.

How to Actually Use a Muscle Map

If you’re looking at a diagram because you’re in pain, stop looking at the spot that hurts.

💡 You might also like: Do You Need Referrals for Medicare? What Most People Get Wrong About Specialist Visits

Pain is a liar.

The site of the pain is rarely the site of the problem. If your knee hurts, look at the diagram of the hip (the gluteus medius) and the ankle. If those are weak or stiff, the knee gets caught in the middle and takes the hit. This is what kinesiologists call the "joint-by-joint" approach.

- Identify the muscle: Sure, find it on the map.

- Look above and below: What muscles cross the joints neighboring the painful area?

- Check the antagonist: If your bicep is tight, your tricep might be too weak to pull it back into balance.

Modern Myths and Muscle Memory

We use the term "muscle memory," but muscles don't actually remember anything. They don't have brains. Memory happens in the cerebellum. When you practice a movement—like a golf swing or typing—your brain creates a "motor program." It gets more efficient at firing the specific sequence of muscles shown on that muscles in the body diagram.

The muscle itself just adapts to the load. If you lift heavy, the fibers (specifically the myofibrils) experience micro-tears. Your body repairs them by making them thicker. This is hypertrophy. But if you don't use them? Atrophy sets in fast. Use it or lose it isn't just a catchy phrase; it's a physiological law.

Practical Steps for Better Muscle Health

Don't just stare at the diagram. Use it as a starting point for better movement.

- Diversify your movement. If you only walk forward, you're only using the muscles in the sagittal plane. Move sideways (frontal plane) and rotate (transverse plane) to wake up the muscles that the 2D diagrams ignore.

- Hydrate for the fascia. Remember that "stuffing" between the muscles? It needs water to slide. Dehydrated fascia becomes "sticky," which leads to that stiff feeling in the morning.

- Load the tissue. Muscles need resistance to stay healthy. This doesn't mean you need to become a bodybuilder, but carrying groceries or doing bodyweight squats keeps those fibers functional.

- Address the "Dark Side" of the Map. Most people focus on the front of the body because that's what we see in the mirror. Spend twice as much time working your "posterior chain"—the muscles on the back of the diagram. Your posture will thank you.

Understanding the muscles in the body diagram is about more than memorizing names for a biology quiz. It’s about recognizing that you are a complex, self-tensioning biological machine. The lines on the paper are just the beginning of the story. Your actual "map" is written in how you move, sit, and breathe every day.

Stop thinking of yourself as a collection of parts and start seeing the connections. The most important "muscle" isn't even on the diagram—it's the nervous system that coordinates the whole chaotic, beautiful mess.

Next Steps for Anatomical Literacy

✨ Don't miss: Understanding Images of Intersex Genitalia and Why Medical Accuracy Matters

To truly apply this knowledge, start by identifying one "hidden" muscle from a 3D anatomy app or a detailed textbook—like the subscapularis or the piriformis—and research its specific function in your daily activities. Next time you feel a "pull" or tightness, consult a functional anatomy guide to see which muscle chain is likely over-stressed. Physical progress starts with accurate mental models.