Honestly, the first time I saw a video of a real life cloak of invisibility, I thought it was a total hoax. It looked like a low-budget green screen effect from a 90s sitcom. But then you start looking at the physics. You look at the research coming out of places like the University of Rochester or the University of California, Berkeley, and you realize we aren't actually that far off. We just have a massive "definition" problem. If you’re expecting a thin, silky fabric that you can throw over your shoulders to sneak into a restricted library section, you’re going to be disappointed. Science doesn't work like magic. It works like a puzzle made of light, mirrors, and some really weird materials called metamaterials that shouldn't technically exist.

People have been obsessed with this forever.

The gap between what we see in movies and what exists in a lab is huge. Right now, if you want to be "invisible," you usually have to stand behind a very specific set of lenses or wear a suit that looks like a walking LED billboard. It’s clunky. It’s experimental. But it is very, very real.

The Lens Trick: How Rochester Made Things Vanish

Back in 2014, researchers at the University of Rochester released something called the "Rochester Cloak." Now, calling it a cloak is a bit of a stretch. It’s actually a series of four standard optical lenses. When you align them perfectly, they bend the light around a central object. If you look through the glass, you see the background perfectly, but whatever is sitting right in the middle of those lenses is just... gone.

It’s a simple trick of geometry.

The cool part about the Rochester setup is that it works in 3D. Most early attempts at a real life cloak of invisibility only worked if you were looking at them from one specific angle. If you moved your head an inch to the left, the illusion shattered. These guys figured out how to keep the background stable even if the viewer moves. It’s not a piece of clothing, though. It’s more like a window that hides what's behind it. Imagine using this on the "A-pillar" of a car—that annoying metal bar that blocks your view of pedestrians when you’re turning. If you could make that pillar invisible using lenses, you’d save lives. That is the kind of practical application that gets engineers excited, even if it’s not as "cool" as a magical cape.

Metamaterials: Bending Light Like Water

To get a true, flexible real life cloak of invisibility, we have to talk about metamaterials. This is where things get genuinely sci-fi. Most natural materials, like glass or water, have a positive refractive index. When light hits them, it slows down and bends a little. Metamaterials are engineered to have a negative refractive index.

Imagine a straw in a glass of water. It looks bent, right? In a metamaterial, the straw wouldn't just look bent; it might look like it’s pointing in the opposite direction or even like it’s completely gone.

💡 You might also like: Dokumen pub: What Most People Get Wrong About This Site

Researchers like Sir John Pendry from Imperial College London pioneered this. The goal is to guide light waves around an object, much like water flows around a smooth rock in a stream. If the light waves can zip around the object and meet back up on the other side without being distorted, the object becomes invisible to the human eye. We’ve already done this perfectly with microwaves. The problem is that visible light has much smaller wavelengths. To manipulate visible light, we have to build metamaterials at the nanoscale. We’re talking about structures smaller than a single red blood cell.

It’s incredibly hard to manufacture.

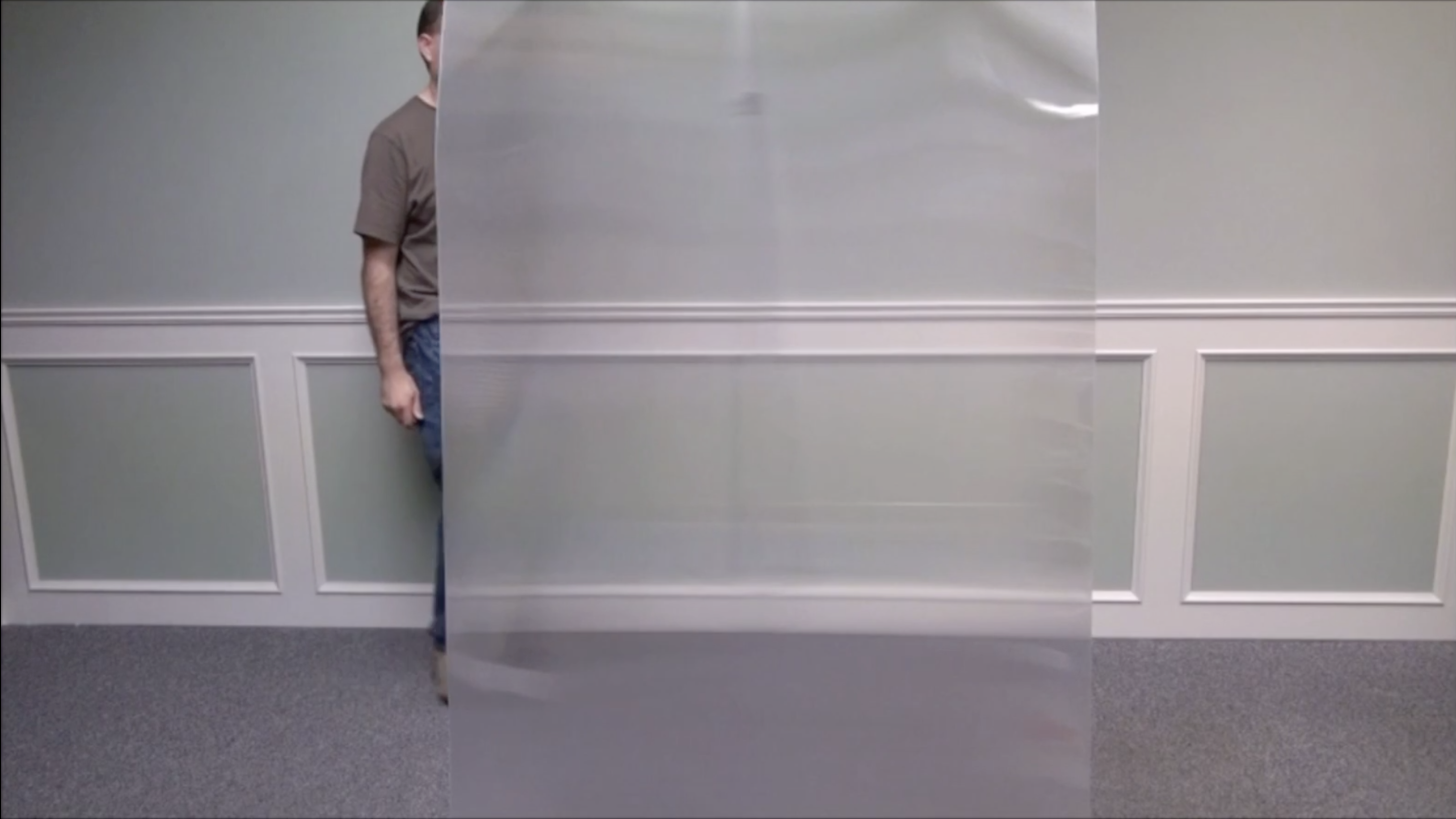

The Invisibility Shield Co. and the Consumer Version

You might have seen the "Invisibility Shield" on Kickstarter or TikTok. A UK-based company actually started selling these. They use a "lenticular lens" array. It’s basically the same technology as those old 3D rulers or posters that change images when you tilt them.

These shields are basically tall, thin sheets of polymer. They don't require power. They work by reflecting the light from the background toward the observer, while the light from the person standing directly behind the center of the shield is scattered away.

- It works best against uniform backgrounds (grass, sand, sky).

- It doesn't work if you're wearing something that contrasts heavily with the sides.

- The person behind the shield sees a blurry mess.

Is it a real life cloak of invisibility? Sort of. It’s more like a high-tech riot shield that makes you look like a smudge. But for $300, it’s the closest thing a regular person can buy right now. It shows that we are moving away from "lab-only" experiments and toward actual physical products.

The Military Interest: Why Stealth Isn't Just for Planes

HyperStealth Biotechnology, a Canadian company, has been showing off a material called "Quantum Stealth." They claim it can hide people, tanks, and even entire buildings. They’ve released videos where a sheet of this material makes a person behind it look like they’ve vanished into thin air.

The military application here is obvious.

📖 Related: iPhone 16 Pink Pro Max: What Most People Get Wrong

If you can hide a tank from a thermal camera or a sniper's scope, you win. But there’s a catch. Most of these "cloaks" work great in photos but fail in high-motion environments. If a tank is moving at 40 mph, a static "invisibility" sheet is going to create a weird visual ripple that the human eye is very good at spotting. Our brains are wired to notice "glitches" in the environment. It’s called the "predator effect," named after the movie. Even if you can’t see the person, you see the shimmering distortion where they should be.

The Heat Problem

Invisibility isn't just about what you see with your eyes. In a modern combat zone, everyone has infrared goggles. You can be visually invisible, but if your body is pumping out 98.6 degrees of heat, you’ll glow like a lightbulb on a thermal sensor.

This is why some scientists are focusing on "thermal cloaks."

Researchers at the University of California, Irvine, developed a material inspired by squid skin. Squids can change their color and texture instantly to blend into the seafloor. This new material uses "reflectin" proteins to manipulate how heat is emitted. By stretching or chemically signaling the fabric, they can make a person appear "cold" to a thermal camera, matching the ambient temperature of the room. A real life cloak of invisibility in the 21st century has to be multi-spectral. It has to hide you from light, heat, and even radar.

Why Don't We Have It Yet?

There are three big hurdles.

- Size: Most metamaterials only work on a microscopic scale. Making a "cloak" big enough to cover a human requires trillions of nano-structures, all perfectly aligned.

- Bandwidth: Most cloaks only work for one color of light. You might be invisible to "green" light, but you'll show up bright purple to everyone else. Hiding across the entire rainbow (white light) is a nightmare.

- The Observer’s View: This is the one nobody talks about. If you are inside a perfect cloak, light is being bent around you. That means no light is hitting your eyes. If you are perfectly invisible, you are also perfectly blind.

What Actually Works Today?

If you want to experience a real life cloak of invisibility today, you have to look at "active camouflage." This is what companies like BaE Systems use for their ADAPTIV program. They cover a vehicle in hexagonal tiles that can change temperature rapidly. By using cameras to scan the surroundings, the tiles mimic the thermal signature of the trees or rocks behind the vehicle.

It’s "digital" invisibility.

👉 See also: The Singularity Is Near: Why Ray Kurzweil’s Predictions Still Mess With Our Heads

It’s not bending light with physics; it’s re-displaying the background on the foreground. It’s basically a giant flexible TV screen wrapped around a tank. It’s expensive, it breaks easily, and it needs a ton of power. But it works.

Future Outlook: The Next 10 Years

We are likely going to see "partial" invisibility become a standard tool in specific industries. Surgeons are looking at "invisible" gloves or tools—using augmented reality (AR) and cameras to "see through" their own hands during delicate operations. This would give them an unobstructed view of the site they are working on.

Pilots already use this. The F-35 fighter jet has a system called MAS (Distributed Aperture System). The pilot wears a helmet that streams video from cameras all around the plane. When the pilot looks down, they don't see the floor of the cockpit; they see the ground 30,000 feet below them. The plane has effectively become a real life cloak of invisibility for the pilot.

Real-World Action Steps

If you are following this tech or want to see it in action, here is how you can actually engage with it without being a billionaire.

Check out the Rochester Cloak DIY. You can actually build this at home. You just need four lenses with specific focal lengths. There are plenty of physics forums that lay out the exact math. It’s a great weekend project if you want to see an object vanish before your eyes using nothing but glass and geometry.

Look into "Lenticular Sheets." If you’re a photographer or a tinkerer, buying a large lenticular sheet online is the cheapest way to play with light-bending. You can experiment with "hiding" objects behind the ridges of the plastic.

Follow the Meta-Journal. Keep an eye on the "Nature Communications" or "Science" journals for the keyword "Metamaterials." That’s where the real breakthroughs happen, usually about 5 to 10 years before they hit the news.

Manage your expectations. We aren't getting the Harry Potter cloak anytime soon. The laws of thermodynamics and optics are pretty stubborn. But we are getting "smart" materials that can trick sensors, lenses that can see through obstructions, and digital overlays that make the physical world feel a lot more transparent. The real life cloak of invisibility is already here—it’s just a lot more "math" and a lot less "fabric" than we expected.