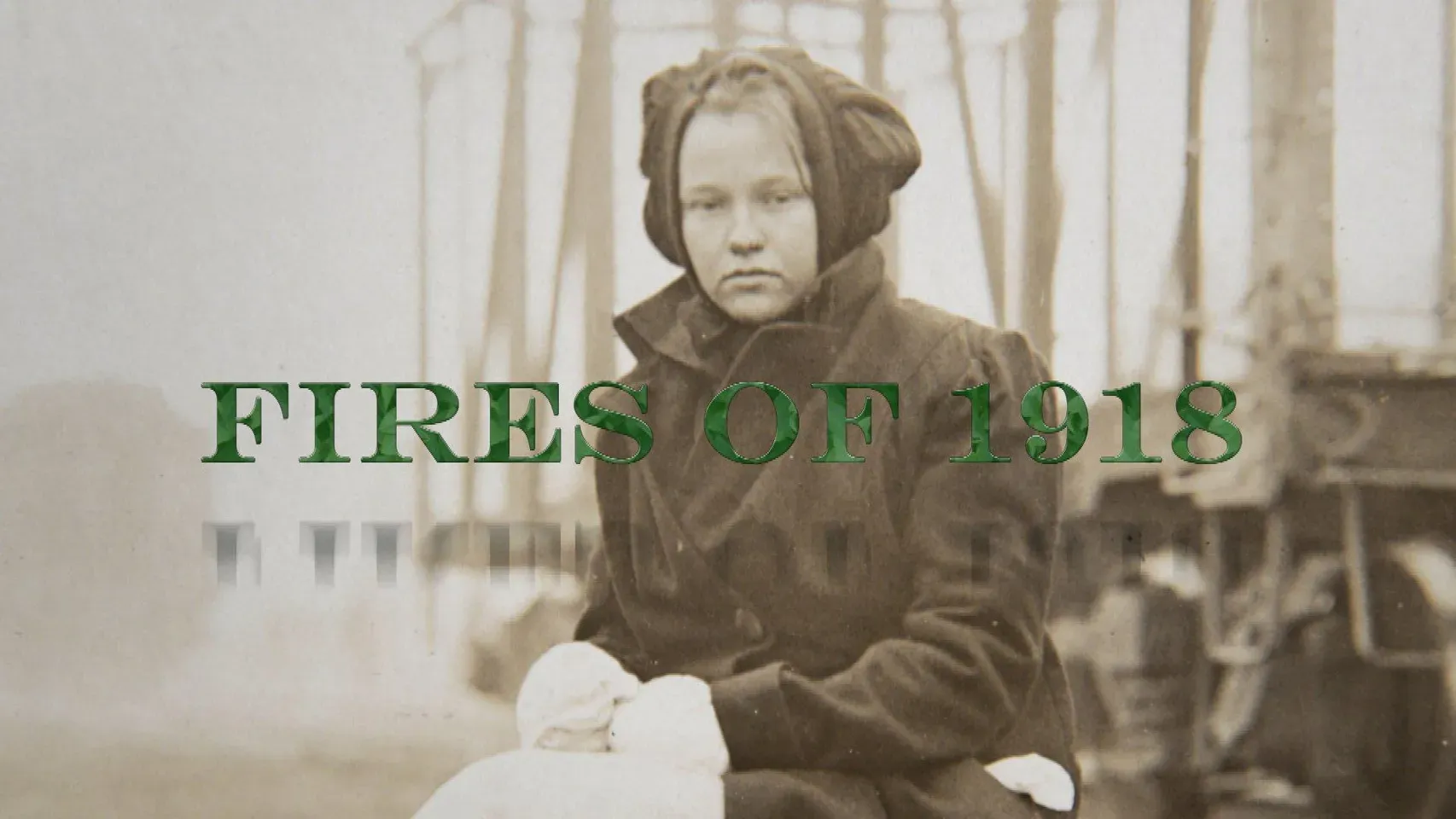

It’s quiet in Moose Lake. You drive up I-35, past the pine trees and the gas stations, and it feels like any other peaceful stretch of Northern Minnesota. But if you pull off the highway and head toward the old lakeside depot, you’re standing on top of a massive, invisible scar. Most people driving to Duluth have no clue that in October 1918, this entire region wasn't just burning—it was vanishing. The Fires of 1918 Museum sits right in the heart of where the world ended for thousands of people.

It’s heavy.

History books usually gloss over this because the 1918 flu pandemic was hogging the headlines back then. But for folks in Carlton and St. Louis counties, the "Great Fire" was the real apocalypse. We’re talking about 453 lives lost in a single day. Some estimates say it was closer to a thousand if you count the people who died later from lung damage or infections. The museum, housed in the beautifully restored Soo Line Depot, doesn't just show you old photos; it drags you into the heat of a fire that was moving so fast people couldn't outrun it in cars.

Why the Fires of 1918 Museum hits different than your average local history spot

You’ve probably been to local museums where it’s just a bunch of dusty spinning wheels and butter churns. This isn't that. When you walk into the Moose Lake Depot, the first thing that hits you is the sheer scale of the devastation documented there.

The fire wasn't just one fire. It was a "firestorm."

Basically, you had a bone-dry autumn, a lot of leftover slash from logging companies, and sparks from passing locomotives. Add 60-mph winds into that mix and you get a literal wall of flame. The museum does a fantastic job of explaining the physics of it without being boring. They have these artifacts—mangled, melted metal that used to be a family’s sewing machine or the rim of a Ford Model T wheel. Seeing iron twisted like taffy tells you more about the temperature of that night than any textbook ever could.

The curators here, many of whom are descendants of survivors, have curated a collection of personal accounts that are, honestly, gut-wrenching. You read about people huddling in the lake, submerged up to their necks for hours while the air above them turned into a blowtorch.

The Cloquet-Moose Lake connection

One thing the Fires of 1918 Museum makes clear is that this wasn't just a Moose Lake tragedy. It was a regional wipeout. Cloquet was almost entirely leveled. The museum displays maps that show the fire's path, cutting a black swathe across 1,500 square miles.

Think about that.

That’s larger than the state of Rhode Island.

🔗 Read more: Why Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station is Much Weirder Than You Think

The stuff they don't tell you in school

Most people think "forest fire" and imagine trees burning. But the 1918 fire was a "slash fire." Because the logging industry was booming, the ground was covered in dry branches and debris. It was a tinderbox waiting for a match.

The museum dives into the controversy of the time. Who was at fault?

The US Railroad Administration ended up paying out millions in claims years later because it was determined that sparks from the trains started the blazes. It was one of the largest legal settlements of its era. You can see the legal documents and the "Fire Relief" records at the museum. It’s a fascinating look at how a community tries to litigate its way out of a disaster while they’re still burying their neighbors.

Survivor stories that stick with you

There's a specific exhibit about the "Death Curve."

On Highway 61, just outside of town, a group of motorists tried to flee the flames. In the blinding smoke, cars crashed into each other. People stepped out of their vehicles and were overcome by the heat and smoke immediately. Twenty-five people died in that one spot. The museum has photos of the aftermath—charred skeletons of cars that look like they belong in a post-apocalyptic movie.

It's grim.

But it's also about the resilience. You see photos of the "Red Cross houses"—tiny, uniform wooden shacks that were built almost overnight so people wouldn't freeze to death when the Minnesota winter hit a few weeks later. These were roughly 14 by 22 feet. Entire families lived in them. The museum actually has information on how these were constructed and where some of the surviving ones are still standing in the area today, repurposed as sheds or cabins.

Visiting the museum: What to expect

If you're planning a trip, keep in mind that the Fires of 1918 Museum is usually a seasonal operation. It’s generally open from May through October, which makes sense because trying to heat an old depot in a Moose Lake January is a losing battle.

- Location: 900 Lake Shore Drive, Moose Lake, MN.

- The Vibe: Quiet, respectful, and deeply informative.

- Time Commitment: Give yourself at least 90 minutes. You’ll want to read the letters.

- Accessibility: It’s an old depot, but they’ve worked hard to make it accessible to everyone.

One of the coolest parts is the mural. There’s a massive painting that wraps around part of the room, depicting the timeline of the fire from the first smoke on the horizon to the total destruction of the town. It gives you a sense of the "before and after" that photos alone can't capture.

💡 You might also like: Weather San Diego 92111: Why It’s Kinda Different From the Rest of the City

The 1918 fire vs. the 1918 flu

It’s weird to think about, but while these people were losing their homes to fire, they were also wearing masks because of the Spanish Flu. The museum doesn't ignore this. They have records of doctors and nurses who were treating burn victims while simultaneously trying to manage a pandemic.

It was a double-hit of trauma.

Some survivors talked about how the smoke actually helped "clear out" the flu, which we know now is totally false, but it shows the desperation of the time. People were looking for any silver lining in a sky that stayed black for days.

Why the Kettle River matters

A lot of the survivors owe their lives to the Kettle River. The museum features stories of families who spent the night in the mud of the riverbanks. There’s one account of a woman who held her children under a wet blanket in the river while the fire roared overhead. She said it sounded like a thousand freight trains passing at once.

The sheer noise of a firestorm is something we don't often think about. It’s not a crackle. It’s a roar.

What most people get wrong about the 1918 disaster

A common misconception is that this was just a "wildfire."

In reality, it was a man-made disaster fueled by nature. The logging practices of the time—leaving "slash" everywhere—created the fuel. The railroads provided the ignition. And the lack of communication meant that by the time people in Moose Lake knew the fire was coming, it was already on their doorstep.

The Fires of 1918 Museum does a great job of clarifying that this wasn't just bad luck. It was a failure of safety protocols and a misunderstanding of how the landscape had been changed by industry.

The Art of the Recovery

You'll see a lot of "Relief" artifacts. The state of Minnesota went into overdrive to help. There were "Fire Sufferer" IDs. There were distributions of donated clothing and food. It’s a side of history that feels very modern—the way a community rallies after a mass casualty event.

📖 Related: Weather Las Vegas NV Monthly: What Most People Get Wrong About the Desert Heat

You can see the hand-written ledgers of what people lost.

- One cow.

- A barn.

- A piano.

- "Everything."

That last one shows up a lot in the records. "Everything."

Actionable steps for your visit

If you're heading up to the Moose Lake area to see the Fires of 1918 Museum, don't just stop at the depot. To really understand the history, you need to see the ground.

- Visit the Riverside Cemetery: There’s a large monument dedicated to the victims. Many of the graves are marked with the same date: October 12, 1918. Seeing the rows of headstones puts the "453 deaths" statistic into a visual perspective that hits hard.

- Drive the "Death Curve" area: It’s located on what is now Highway 61. While there isn't a massive neon sign, knowing the history of that stretch of road changes how you look at the ditches and the trees.

- Check out the Soo Line Depot architecture: Even if you aren't a history buff, the building itself is a gem. It’s one of the few structures that survived or was rebuilt quickly after the fire, symbolizing the town's refusal to die.

- Talk to the volunteers: Seriously. Most of the people working there have a personal connection to the fire. They have stories passed down through their families that aren't on the placards. Ask them about their grandparents.

- Support the Carlton County Historical Society: They do the heavy lifting of keeping these records alive. If you can't make it to Moose Lake, their digital archives are a goldmine of 1918 fire photos and primary sources.

The fire changed the ecology of Northern Minnesota too. The white pine forests that were logged and then burned never really came back the same way. What you see now—the birch and the poplar—is the "second growth" that rose from the ashes.

Every time you look at the woods around Moose Lake, you're looking at a 100-year-old recovery project.

The museum is a reminder that while the fire was fast, the healing is slow. It’s a place that respects the dead but celebrates the people who crawled out of the ditches, wiped the soot off their faces, and decided to build the town all over again.

Don't just drive past it.

Stop.

Read the names.

Look at the melted sewing machines.

It’s one of the most powerful small-town museums in the Midwest, and it deserves a spot on your Minnesota bucket list. You’ll leave with a much deeper appreciation for the ground you're walking on and the people who held onto it when everything was literally going up in flames.