Let’s be honest. Ordering a steak medium-well often gets you some side-eye from the "purists" at the table. You know the type—the ones who think if it isn’t practically mooing, you’ve ruined a perfectly good piece of beef. But here’s the thing: sometimes you just want a warm, firm, and thoroughly cooked center without the metallic tang of a rare steak. Achieving the perfect medium well temp for steak isn't about overcooking it until it feels like a leather boot; it’s actually a pretty precise science that requires a bit more finesse than just leaving it on the grill for "a long time."

The Magic Number: What Temperature is Medium Well?

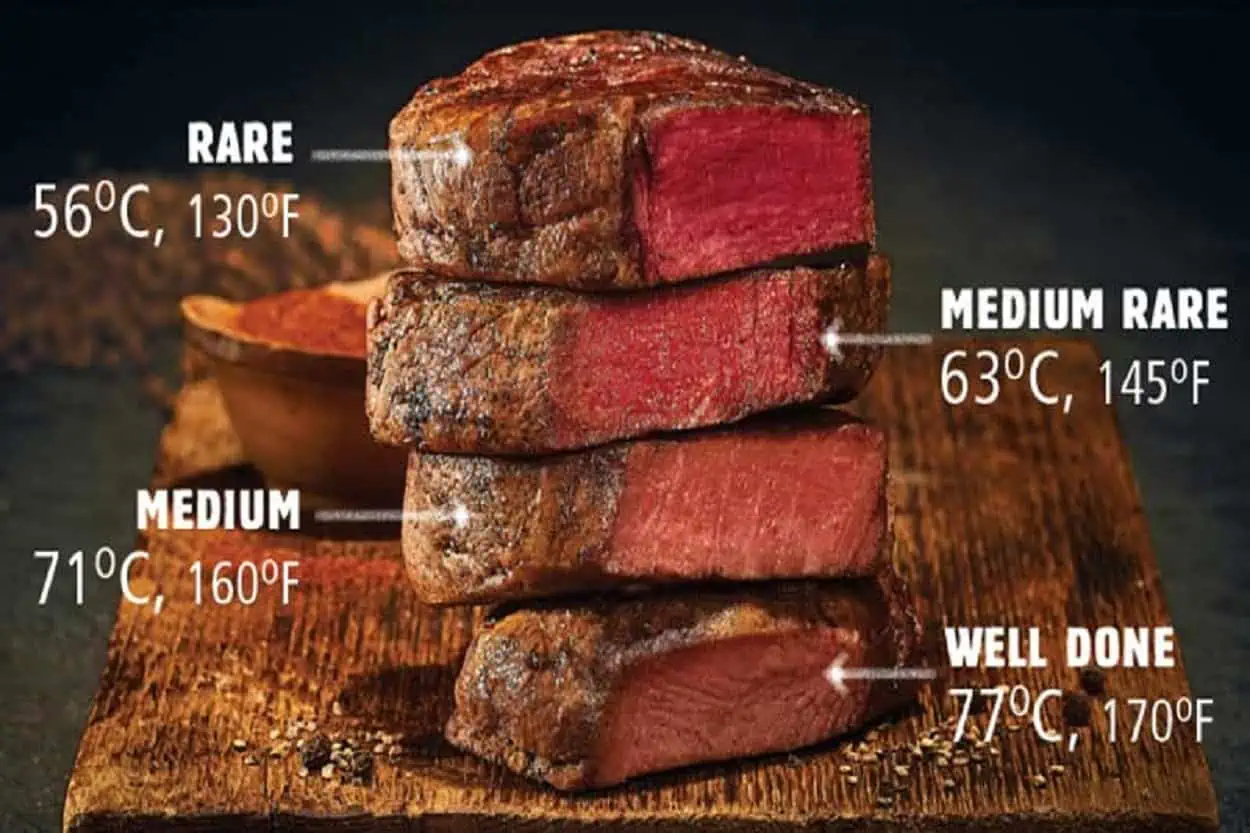

If you're looking for a specific number, you need to pull that steak off the heat when your instant-read thermometer hits exactly 150°F ($65.5°C$). Now, don’t just leave it there. Carry-over cooking is a real thing. As the steak rests on your cutting board, the internal temperature is going to climb another five degrees. You’re aiming for a final, rested medium well temp for steak of 155°F ($68°C$).

At this stage, the meat is mostly gray-brown throughout. You’ll see a thin, pale band of pink right in the center. It’s not "bloody" (though we know that red liquid is actually myoglobin, not blood), and the texture is significantly firmer than a medium steak. According to the USDA, 145°F is the minimum safe internal temperature for whole cuts of beef, so medium-well puts you comfortably in the safety zone while still retaining enough moisture to be enjoyable.

Why 155°F is the Hardest Temp to Nail

It’s actually easier to cook a steak rare or well-done than it is to hit medium-well. Why? Because the window of perfection is incredibly narrow. If you pull it too early, you're at medium. If you're distracted by a text message for sixty seconds, you’ve hit well-done and the juices are gone.

The protein fibers—specifically the myosin and actin—have largely denatured and tightened by the time you reach 150°F. They are squeezing out moisture. This is why a medium-well steak can turn into a dry disaster if you aren't careful. You need enough heat to render the fat, especially on a ribeye, but not so much that you turn the muscle fibers into straw.

The Feel Test vs. The Digital Probe

Old-school chefs like Anthony Bourdain used to swear by the "finger test" or the "face test." You know, poking the fleshy part of your palm to see if it feels like a certain doneness. Honestly? That's a great way to serve a mediocre dinner. Professional kitchens use probes because every hand is different and every steak has a different density.

If you must know, a medium-well steak should feel like the base of your thumb when you press your pinky and thumb together. It should have a lot of resistance. No "squish." But if you’re serious about your $40 Porterhouse, buy a Thermapen or a similar high-quality digital thermometer. It’s the only way to be sure you’ve hit that specific medium well temp for steak without cutting into it and letting all the steam and juice escape.

Best Cuts for This Temperature

Not all steaks are created equal when you're heading toward the well-done side of the spectrum. If you try to cook a lean Filet Mignon to medium-well, you’re probably going to be disappointed. It lacks the fat to stay lubricated.

- Ribeye: This is the king of medium-well. The high fat content (marbling) means that even as the meat gets firm, the fat is melting and keeping everything buttery.

- Skirt or Hanger Steak: These have coarse fibers. While often served medium-rare, a medium-well skirt steak can be delicious if sliced thin against the grain.

- Strip Steak: A solid middle ground. It has enough of a fat cap to survive the higher heat.

Avoid lean cuts like Top Round or Eye of Round at this temperature. They will become incredibly tough.

The Myth of "Ruining" the Meat

There’s this weird elitism in the BBQ and steak world. But some of the best meat scientists, like Greg Blonder, point out that fat rendering actually peaks at higher temperatures. At a medium-well temp, you are getting maximum flavor from the fat breakdown. You just have to balance that against the loss of water from the muscle.

If you’re using a dry-aged steak, be even more careful. Dry-aged beef has less water to begin with, so it cooks faster. You might find that a dry-aged steak hits 155°F much quicker than a grocery store choice cut.

Techniques for Success

Stop flipping the steak every thirty seconds unless you're using the "constant flip" method popularized by J. Kenji López-Alt. For medium-well, a sear-and-move strategy works best. Sear it hard on both sides to get that Maillard reaction (that's the brown crust), then move it to a cooler part of the grill or into a 300°F oven.

Cooking it entirely over high heat to reach medium-well will result in a "bullseye" effect: charred on the outside, gray on the edges, and a tiny dot of pink in the middle. By using indirect heat for the final stretch, you ensure the heat drifts slowly toward the center, giving you a more uniform color.

- Resting: This is non-negotiable. If you cut a steak at 155°F immediately, the juice will run all over the plate. Wait at least seven minutes.

- The Foil Tent: Don’t wrap it tight! You’ll steam the crust and make it soggy. Just drape a piece of foil over it loosely.

- Butter Basting: Since you're losing some moisture at this temp, basting with butter, garlic, and thyme during the last two minutes of cooking adds a layer of fat that mimics juiciness.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Most people fail because they don't account for the thickness of the meat. A thin, half-inch supermarket steak will hit medium well temp for steak in about three minutes. You can't really "manage" that temperature. You want a steak that is at least 1.5 inches thick. This gives you the thermal mass necessary to control the climb from 130°F to 150°F.

Another mistake? Taking the steak straight from the fridge to the pan. While some modern tests suggest this matters less for rare steaks, for medium-well, it's a disaster. The outside will be burnt to a crisp before the inside even hits 100°F. Let it sit out for 30–45 minutes. It makes a difference in how evenly the heat travels.

The "Grey Band" Problem

A "grey band" is that overcooked layer of meat between the crust and the center. It’s usually caused by too much direct heat for too long. To minimize this, use a cast-iron skillet to get your crust fast, then immediately turn the heat down or finish in the oven. You want the transition from crust to pink to be as sharp as possible.

Actionable Steps for Your Next Cook

To get that perfect 155°F finish, follow these specific steps:

- Dry the Surface: Use paper towels. A wet steak won't sear; it will steam. You can't get a good medium-well finish if the outside looks like boiled luggage.

- Season Heavily: Higher temps can dull some of the "beefy" flavor, so don't be shy with the kosher salt and coarse black pepper.

- Target Pull Temp: Pull the steak at 150°F. This is the "danger zone" where people wait too long. Trust the carry-over cooking.

- Check the Grain: Once rested, slice against the grain. Even a perfectly cooked medium-well steak will feel tough if you slice with the muscle fibers.

If you follow these steps, you’ll end up with a steak that satisfies the craving for a fully cooked meal without sacrificing the soul of the beef. It’s about control, not just heat. Get your thermometer ready, pick a marbled cut, and ignore the critics. A well-executed medium-well steak is a masterclass in temperature management.

Ensure your thermometer is calibrated by checking it in a glass of ice water (it should read 32°F) before you start. This prevents a 5-degree error from ruining an expensive dinner. Once you master the 150°F pull, you'll never have a dry steak again.