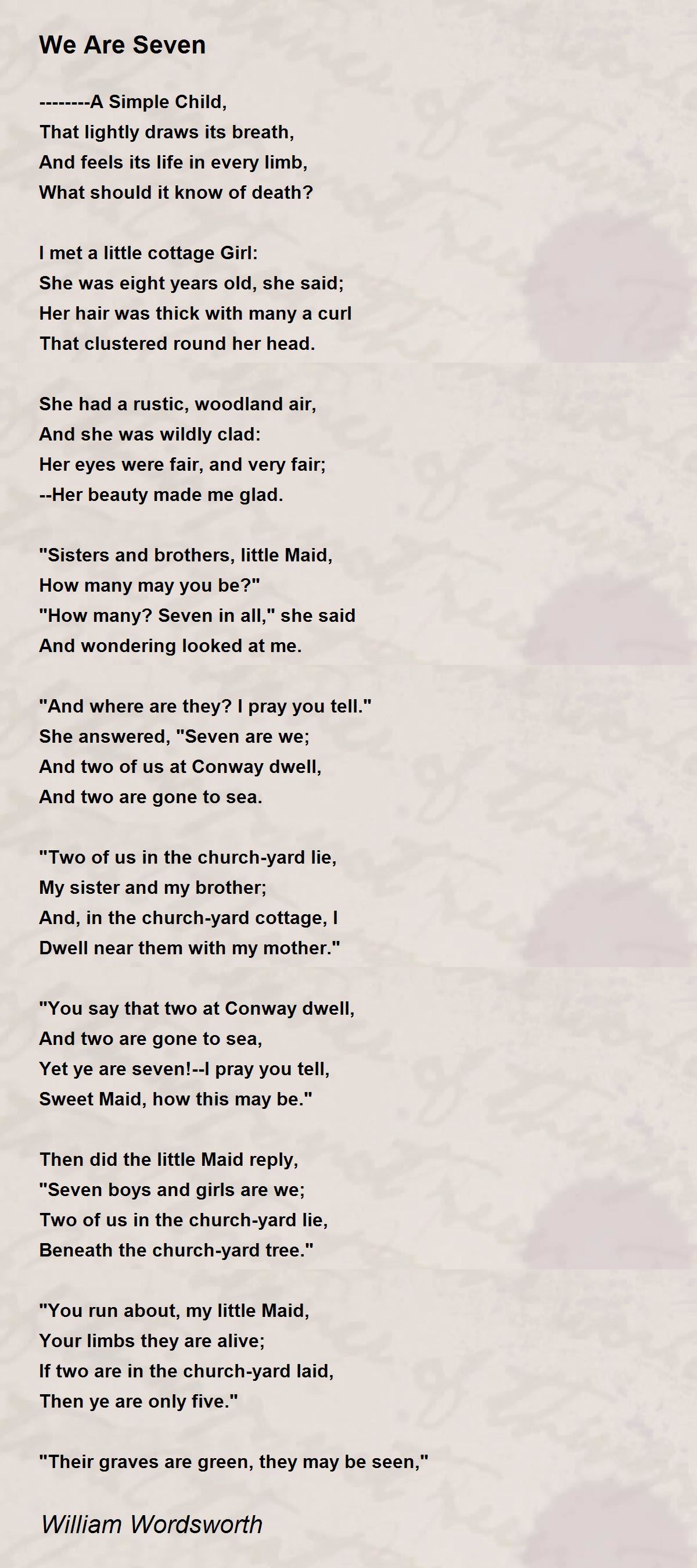

William Wordsworth was kind of a rebel, even if we usually picture him as a stuffy guy in a Victorian portrait. Back in 1798, when he published Lyrical Ballads with his friend Samuel Taylor Coleridge, people were used to "high" poetry. They wanted grand metaphors and flowery language about Greek gods. Then comes this weird little poem about a guy arguing with an eight-year-old girl in a churchyard. It’s called the We Are Seven poem, and honestly, it’s one of the most frustratingly beautiful things ever written in the English language.

The premise is dead simple. A sophisticated, adult narrator meets a young cottage girl. He asks how many siblings she has. She says, "Seven." He looks around, sees only her, and starts doing the math. Two are in Conway. Two are at sea. Two lie in the churchyard. He tries to correct her. He tells her that if two are dead, they don't count. They are gone. Spirits in heaven.

She doesn’t care. To her, they are still there.

The Logic Gap in the We Are Seven Poem

It’s a clash of worldviews. You've got the adult, who represents Enlightenment-era cold logic, and the child, who represents a primal, intuitive connection to life. The man is obsessed with counting. He wants a census. He wants the "truth" of the graveyard. But the girl? She eats her porringer by their graves. She knits her stockings there. She sings to them.

For the little girl in the We Are Seven poem, death isn't a wall. It’s just a different way of being in the family.

Think about how we view loss today. We talk about "closure" and "moving on." We try to rationalize the absence of people we love by looking at death certificates and mourning rituals. Wordsworth was tapping into something much older—the idea that our bonds with people aren't severed just because their hearts stopped beating. It’s a bit haunting if you think about it too long. The girl is literally hanging out with corpses, yet she’s the one who seems full of life, while the narrator comes across as a pedantic jerk.

👉 See also: AP Royal Oak White: Why This Often Overlooked Dial Is Actually The Smart Play

Why Wordsworth Wrote It This Way

Wordsworth actually wrote the last line first. He was staying at Alfoxden House and talking to Coleridge about the "child’s sense of death." He wanted to show that children have a "natural" wisdom that adults lose as they grow up and get obsessed with spreadsheets and "facts."

The poem uses a ballad meter. It’s catchy. It sounds like a nursery rhyme, which makes the subject matter—dead siblings—feel even more jarring.

- Jane went first. She "lay moaning in her bed" until God released her.

- John was next. He went when the grass was dry, following his sister.

- The narrator's frustration. He literally yells at her by the end: "But they are dead; those two are dead!"

It’s basically the 18th-century version of an internet argument where one person is using logic and the other is using vibes. And the vibes win.

The Real-World Inspiration

This wasn’t just a fever dream Wordsworth had. In 1793, he actually met a little girl at Goodrich Castle in Herefordshire. He remembered her curly hair and "wild" appearance. She told him about her family, and that conversation stuck in his brain for five years until he sat down to write.

It’s interesting because Wordsworth was dealing with his own stuff back then. He had a daughter in France, Caroline, whom he couldn't see because of the war. He was living a life of fragmented family units. Maybe that’s why the idea of a family staying "seven" despite distance and death resonated so much with him. He wasn't just writing a cute story; he was wrestling with the permanence of human connection.

✨ Don't miss: Anime Pink Window -AI: Why We Are All Obsessing Over This Specific Aesthetic Right Now

How the Poem Changed Literature

Before the We Are Seven poem, kids in literature were usually just miniature adults. They talked like philosophers and acted like tiny saints. Wordsworth gave us a real kid. She’s stubborn. She’s a bit repetitive. She’s focused on her own reality.

This shifted everything. It paved the way for the Romantic movement’s obsession with childhood. Without this poem, we probably don't get the nuanced portrayals of youth in later 19th-century novels. It challenged the idea that being "rational" was the highest form of human existence. Sometimes, the "irrational" belief that love outlasts the grave is the more human way to live.

Addressing the "Morbid" Criticisms

Some critics over the years have found the girl’s behavior a bit creepy. They point out that she’s basically living in a cemetery. She’s "running wild" and doesn't seem to have a proper parental figure around. Is she traumatized? Is she in denial?

Honestly, that’s the adult narrator’s perspective leaking into the criticism. If you look at the text, she isn't sad. She’s at peace. She’s integrated the "dead" members of her family into her daily chores and play. It’s a radical form of grief processing that doesn't involve "letting go."

Most people get this wrong: They think the poem is about a girl who doesn't understand death. But she describes Jane’s "moaning" and John’s burial quite clearly. She understands the physical reality perfectly well. She just refuses to let that physical reality dictate her emotional reality.

🔗 Read more: Act Like an Angel Dress Like Crazy: The Secret Psychology of High-Contrast Style

Key Lessons from the We Are Seven Poem

If you're reading this poem today, it’s worth looking at your own life. How often do we let "facts" get in the way of meaningful connections? We live in a world of data. We track everything. But the girl reminds us that some things—like the number of people in a family—aren't up for debate by outsiders.

- Family is a state of mind. You define who belongs, not the law or biology or a cemetery plot.

- Rationality has limits. You can't "logic" someone out of their feelings or their faith.

- Childhood perspective is valid. Just because a child hasn't learned the "rules" of the world yet doesn't mean their view is wrong.

How to Engage with Wordsworth Today

Don't just read it on a screen. Go to a park. Or a quiet spot. Read it out loud. Notice how the rhythm speeds up when the narrator gets annoyed. Feel the weight of the girl’s final line: "Nay, we are seven!"

It’s a short read, but it stays with you. It’s a reminder that we are more than just the sum of our living parts.

To really dive into the world of the We Are Seven poem, try these steps:

- Compare it to "Lucy Gray." This is another Wordsworth poem about a child and death. It’s much more ethereal and ghost-like.

- Visit the Lake District (if you can). Seeing the actual landscapes Wordsworth walked helps you understand the "wildness" he describes in the girl.

- Write your own "count." Think about the people who shaped you but are no longer here. Do you still count them in your "total"? Most of us do, even if we don't realize it.

Ultimately, Wordsworth wasn't trying to win an argument. He was trying to show that the human heart doesn't follow the rules of arithmetic. The girl’s stubbornness is her strength. She wins the poem not because she’s right about biology, but because she’s right about love. The narrator walks away frustrated, but the reader walks away changed. That’s the power of a poem that refuses to let the dead stay buried.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Understanding:

- *Read the full text of Lyrical Ballads (1798).* Focus specifically on the Preface, where Wordsworth explains why he used "the real language of men."

- Research the "Grasmere Journal" by Dorothy Wordsworth. William’s sister was a massive influence on his work, and her observations of local children often made it into his poems.

- Analyze the stanza structure. Look at how the rhyme scheme (ABAB) creates a sense of inevitability, mirroring the girl's unshakable conviction.