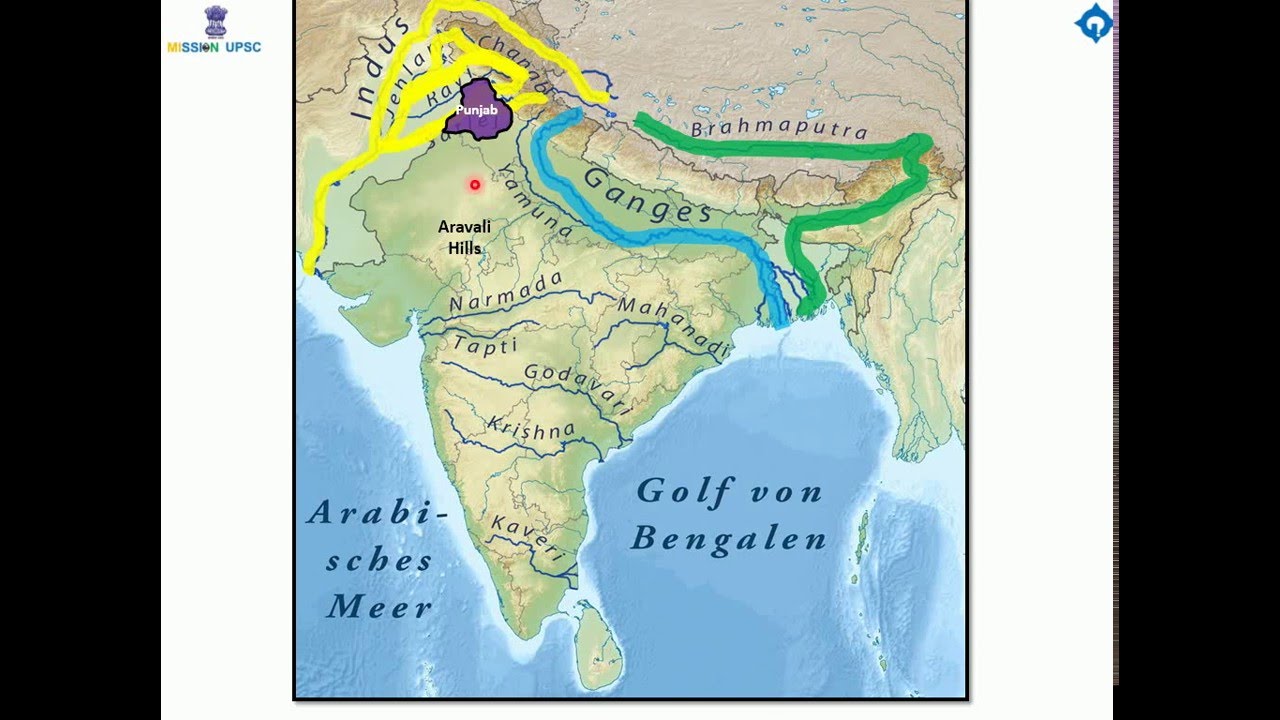

Look at any satellite image of South Asia and you’ll see it. A massive, shockingly green gash across the northern part of India, spilling into Pakistan and Bangladesh. That’s the Indo-Gangetic Plain. But if you're looking at a standard map of Gangetic plain regions, you're likely missing the nuance of why this specific patch of dirt basically runs the world’s most populous subcontinent.

It's huge.

Seriously, we're talking about roughly 700,000 square kilometers of flat, alluvial land. It stretches from the edge of the Thar Desert in the west all the way to the lush, wet delta of the Bay of Bengal. Most people think it’s just one big flat field. It isn't. The topography shifts subtly, but those shifts dictate everything from where the wheat grows to why millions of people migrate every season.

The Three Hidden Zones on Your Map

Most high school geography books split the map into three sections. You’ve got the Upper, Middle, and Lower plains. That’s a bit oversimplified.

In the west, you have the Indus-Ganges watershed. This is high ground. Well, high for a plain. It’s mostly in Haryana and Punjab. Here, the ground is firmer. The map shows a transition from the arid sands of Rajasthan to the fertile "breadbasket." It’s basically the engine room of India's food security. You see lots of tube wells and straight-line canals here.

Then you hit the Middle Gangetic Plain. This is Uttar Pradesh and Bihar territory. The rivers start getting lazy. They meander. If you look at a topographical map of Gangetic plain dynamics in this region, you’ll notice "oxbow lakes." These are scars left behind when a river like the Kosi or the Gandak gets bored of its path and just... moves.

"The Kosi River is famous for this. It’s called the 'Sorrow of Bihar' because it can shift its channel by dozens of kilometers in a single monsoon season." — Dr. R.K. Sinha, river ecology expert.

Finally, there’s the Lower Plain. West Bengal and Bangladesh. This is where the earth basically turns into water. The map here is a mess of distributaries. It’s the largest delta on the planet. If you’re hiking here, you aren't walking on solid rock; you’re walking on silt that traveled thousands of miles from the Himalayas.

Why the Dirt Matters More Than the Lines

Let's talk about alluvium. It sounds boring. It’s actually the secret sauce.

💡 You might also like: Why Promontory Point at Burnham Park Stays Chicago's Best Unspoiled Escape

When you look at a map of Gangetic plain soil types, you see two main flavors: Khadar and Bhangar.

- Bhangar: This is the old stuff. It’s higher up, away from the current river floodplains. It’s full of "kankar" or calcium carbonate nodules. It’s good, but it’s not the superstar.

- Khadar: This is the gold. It’s the new soil deposited by every flood. It’s light, sandy, and incredibly fertile.

Farmers in the Middle Plain pray for the "right" kind of flood. Too much and the village is gone. Too little and the Khadar doesn't get replenished. It’s a delicate, terrifying balance. You’ve got millions of people living on what is essentially a giant, wet sponge.

The Himalayan Connection

You can’t understand the plain without looking north. The Himalayas are the reason the plain exists. About 50 million years ago, the Indian plate smashed into the Eurasian plate. It created a giant trough or "foredeep."

Rain and ice spent millions of years grinding down the mountains and dumping the debris into that hole. That debris is the Gangetic Plain. So, when you look at a map, remember you’re looking at a 6-kilometer-deep pile of mountain dust.

The Terai region is the transition zone. It’s the marshy, jungle-filled strip where the mountains meet the flatlands. If you’re a wildlife enthusiast, this is where the map gets interesting. Jim Corbett National Park and Dudhwa are tucked right into this crease. It’s damp, humid, and used to be a massive malaria trap until the mid-20th century.

Urban Sprawl and the 400-Person Problem

Here is a weird stat: the population density here is insane. In some parts of Bihar or West Bengal, you’re looking at over 1,000 people per square kilometer.

If you overlay a population density map on a map of Gangetic plain water resources, they match perfectly. People go where the water is easy to find. This has created a massive urban corridor. From Delhi to Kanpur to Patna to Kolkata, it’s almost one continuous strip of humanity.

- Delhi: The gateway. Built on the Yamuna.

- Varanasi: Where the river turns north, which is spiritually "auspicious."

- Patna: Once Pataliputra, the seat of empires, sitting at the confluence of four major rivers.

The infrastructure is struggling. The map of the plain is now a map of smog. Because the Himalayas act like a giant wall, the cold air in winter traps pollutants from crop burning and factories right over the plain. It’s a geographic trap.

The Monsoon Pulse

The entire map changes colors depending on the month. In June, it’s brown and dusty. By August, it’s a brilliant, neon green.

The Southwest Monsoon hits the Bay of Bengal, turns left because of the mountains, and marches up the Gangetic Plain. It’s a conveyor belt of rain. The map shows more rainfall in the east (Kolkata gets about 1,600mm) and less in the west (Delhi gets around 600mm).

🔗 Read more: Why the Mummies of Guanajuato Museum Still Haunts and Fascinates Us

This gradient determines what you eat. East? Rice and fish. West? Wheat and dairy. It’s that simple.

Realities of Climate Change on the Map

We have to be honest: the map is shrinking.

Rising sea levels are pushing saltwater into the Sundarbans. This is the southern tip of the plain. Saltwater kills crops. It forces people to move north.

Meanwhile, the glaciers in the Himalayas—the source of the Ganga and Yamuna—are receding. In the short term, this means more water and more floods. In the long term? The rivers could become seasonal. If that happens, the map of the Gangetic plain as we know it—a lush, fertile paradise—could turn into a dust bowl.

Actionable Insights for Navigating the Plain

If you're planning to travel, study, or invest in this region, don't just look at a political map. Look at the water.

- Timing: Don't visit the Middle or Lower plains in July or August unless you like wading through knee-deep water. The flooding isn't a "glitch"; it’s a feature of the geography.

- Travel: Use the rail network. The plain is so flat that the British were able to lay thousands of miles of track with almost no tunnels or steep grades. It’s the easiest way to see the transition from the wheat fields of the west to the rice paddies of the east.

- Culture: Notice the "Ghats." In every city on the map along the Ganga, the life of the town is oriented toward the riverbank.

- Environment: If you’re looking at land, check the elevation. Even a two-meter difference in elevation on a map of Gangetic plain can mean the difference between a dry basement and a total loss during the monsoon.

The Gangetic Plain isn't just a location. It’s a living, breathing, shifting entity that supports nearly a tenth of the human population. Understanding its map is basically understanding the pulse of India itself. Check the soil, watch the clouds, and always keep an eye on the mountains to the north. That's where it all begins.