You probably haven’t heard the name Louis Marx in a while. Honestly, unless you’re a hardcore collector or someone who grew up in the fifties, it’s just another name from the history books. But here is the thing: Louis Marx and Company was once the absolute center of the toy universe. By the mid-1950s, this company wasn't just big; it was the largest toy manufacturer on the planet.

What’s wild is that Louis Marx himself, the guy Time Magazine dubbed the "Toy King" in 1955, achieved all of this while basically refusing to spend a dime on advertising. While everyone else was scrambling to buy TV spots, Marx just... didn't. He believed that if you gave a kid a toy that was better and cheaper than the competition, the toy would sell itself. And for about fifty years, he was right.

Why Louis Marx and Company Still Matters

The company's philosophy was refreshingly simple: "Give the customer more toy for less money." It’s a bit of a cliché now, but Marx lived by it. He was a master of the "knock-off," though he preferred to call it competition. If a competitor came out with a $10 electric train, Marx would find a way to make a $4 version that was just as fun and twice as durable.

He didn't just copy, though. He improved. When he saw the "Joy Line" trains doing okay in the thirties, he bought the company and turned them into a massive success. He had this six-point checklist for what made a toy great: familiarity, surprise, skill, play value, comprehensibility, and sturdiness. If a toy didn't hit those marks, it didn't get made.

The Big Wheel and the Robots

If you’ve ever seen a Big Wheel, you’ve seen the legacy of Louis Marx and Company. Introduced in 1969, it was a low-slung plastic tricycle that became a cultural icon. It wasn't just a bike; it was a way for kids to do power slides on the driveway without breaking their necks.

🔗 Read more: Enterprise Products Partners Stock Price: Why High Yield Seekers Are Bracing for 2026

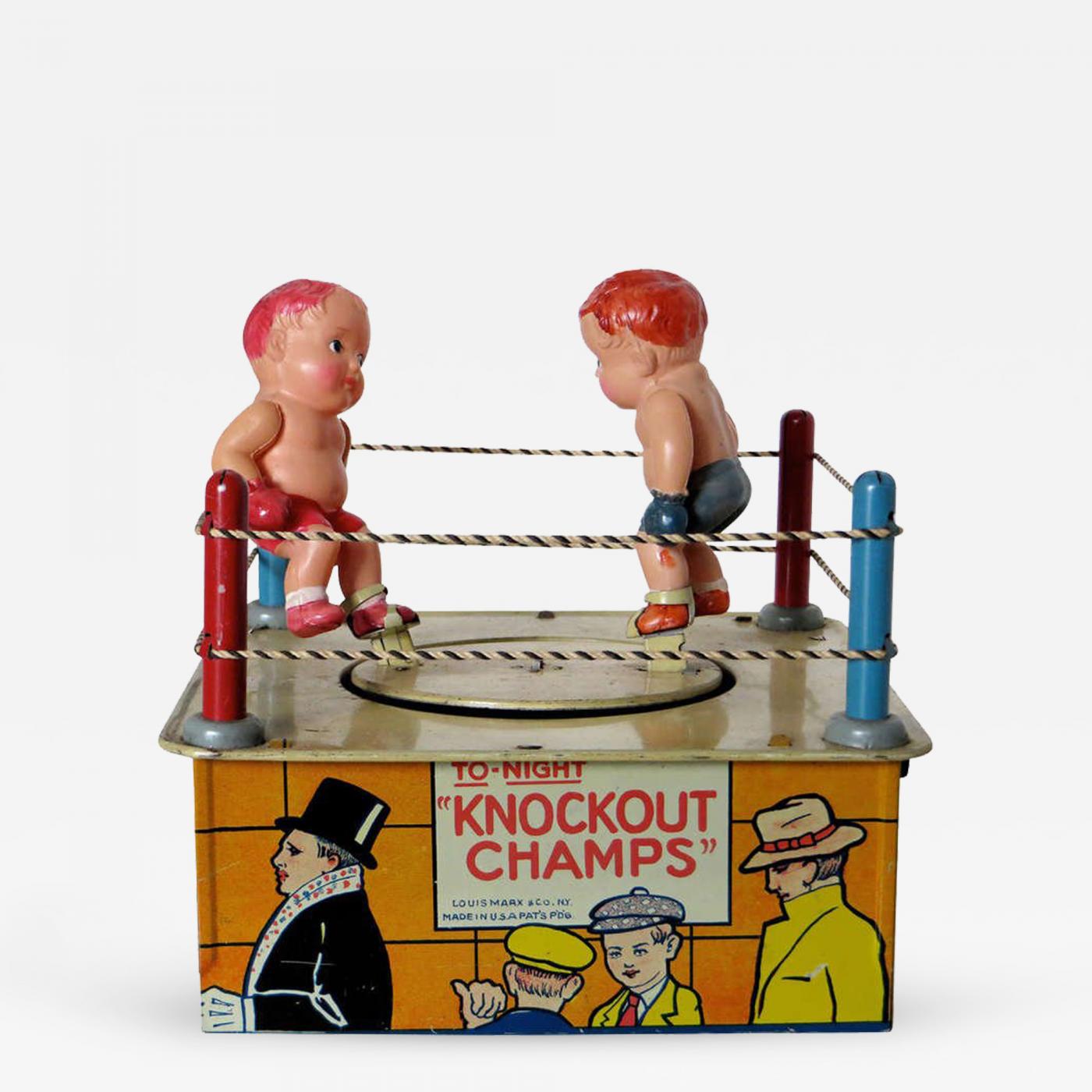

Then there were the Rock 'em Sock 'em Robots. Introduced in 1964, these became a staple of American childhood. The "Red Rocker" and the "Blue Bomber" duking it out until one of them got their block knocked off? That was Marx. It was simple, it was plastic, and it worked every single time.

The Secret Strategy: Lowering the Ceiling

One of the most fascinating things about how Louis Marx and Company operated was where they put their factories. Instead of staying in New York City, they moved to places like Erie and Girard, Pennsylvania, and Glen Dale, West Virginia.

Why? Because the labor was cheaper and the people were desperate for work during the Great Depression.

- The Glen Dale Plant: This was a quarter-mile-long former aircraft factory. At its peak, it was pumping out more toys than any other facility in the world.

- The Erie Plant: This was the "Monkey Works," named after the Zippo climbing monkey toy that helped make Marx a millionaire by 1922.

- Plastics Revolution: Marx was one of the first guys to realize that tin was the past and plastic was the future. He pivoted hard in the late 1940s, which is why your grandpa's old toy soldiers are likely Marx "unbreakables."

Marx was also a king of licensing. Long before every toy had a movie tie-in, he was making playsets for Gunsmoke, Roy Rogers, and Walt Disney. He understood that kids wanted to play inside the stories they saw on the screen.

💡 You might also like: Dollar Against Saudi Riyal: Why the 3.75 Peg Refuses to Break

The Tragic Sale to Quaker Oats

By the early 1970s, Louis Marx was getting older. He was in his 70s and famously said, "Toys is a young man's business." None of his kids were ready or willing to take the reigns. So, in 1972, he sold the whole empire to the Quaker Oats Company for $52 million.

It was a disaster.

Quaker Oats already owned Fisher-Price, and they thought they could just apply the same formula to Marx. They were wrong. They didn't like the "military" toys because it didn't fit their wholesome cereal image, so they cut one of the company's most profitable lines. They raised the overhead. They lost the "gut feeling" that Louis had for what kids actually wanted.

After only three years of losses, Quaker sold the company to a British firm, Dunbee-Combex-Marx, for about $15 million. It was a fire sale. By 1980, the company that once ruled the world filed for bankruptcy.

📖 Related: Cox Tech Support Business Needs: What Actually Happens When the Internet Quits

Spotting a Real Marx Today

If you’re digging through an attic or hitting an estate sale, look for the logo: a circle with the letters "MAR" and a large "X" through them. That’s the classic mark.

Collectors today lose their minds over the lithographed tin wind-up toys from the thirties. The Marx Merry Makers mouse band is legendary. It’s a group of four tin mice playing instruments, and if you find one in its original box, you’re looking at a $1,000 bill, easily.

The playsets are also huge. The "Fort Apache" or "Johnny West" sets are prized because they usually have dozens of tiny pieces that kids (obviously) lost in the dirt fifty years ago. A complete, boxed set is a rare find.

Actionable Insights for Collectors

If you want to start collecting or just value what you have, here is what actually matters:

- Check the Lithography: On older tin toys, look for scratches or "spidering" in the paint. High-quality lithography is what makes Marx toys look like art.

- The "Working" Premium: Wind-up mechanisms often fail. If the spring is snapped, the value drops by 50% or more. Never over-wind an old Marx toy; the metal is brittle.

- Box is Everything: For 1960s plastic playsets, the box is often worth more than the figures inside. Don't throw away that beat-up cardboard.

- Avoid the "Renaissance" Fakes: In the 90s, some people tried to revive the Marx name and produced new versions of old toys. They look too clean and lack the original "MARX" stamp on the bottom.

Louis Marx and Company didn't just make toys; they made the 20th-century childhood. They proved that you could be the biggest company in the world just by making things that lasted and making sure every kid, no matter how little money their parents had, could afford one.

To start your journey into Marx collecting, your best bet is to visit a dedicated toy museum like the one in Wheeling, West Virginia, or start browsing reputable auction sites to get a feel for the current market prices of "Best of the West" figures versus the earlier tin wind-ups. Don't buy the first thing you see; the Marx catalog was so massive that there is always another rare variant just around the corner.