Lou Reed didn't want your approval. He wanted your attention, sure, but he wasn't looking for a hug or a chart-topping hit that everyone could whistle while doing the dishes. When we talk about Lou Reed of The Velvet Underground, we’re talking about a guy who took the "peace and love" ethos of the 1960s and essentially threw a brick through its window.

He was difficult. He was often mean. But he was also right about where music needed to go.

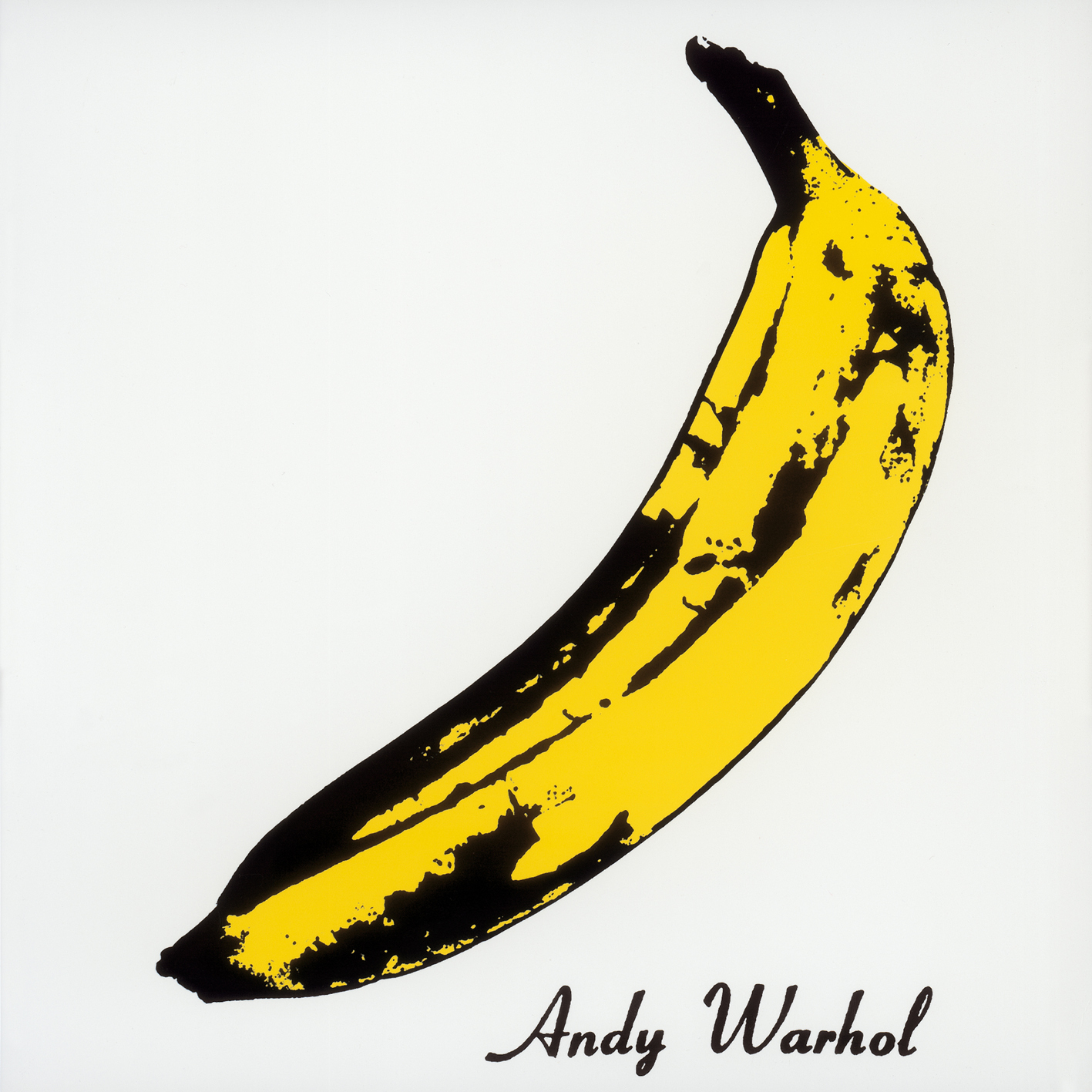

Most people today know the banana on the album cover. They know "Walk on the Wild Side" because it plays in every grocery store in America now, which is a hilarious irony if you actually listen to the lyrics. But to understand the engine behind the band that changed everything, you have to look at how Reed fused high-brow literature with the seediest street corners of New York City. He wasn't just a rock star; he was a journalist with a distorted guitar.

The Reality of Lou Reed of The Velvet Underground

Before the Velvets, rock lyrics were mostly about holding hands or some vague psychedelic dreamscape. Lou changed the vocabulary. He brought in the junkies, the drag queens, and the sadomasochists. He brought in Delmore Schwartz.

Schwartz was Reed’s mentor at Syracuse University, and he taught Lou that you could use simple language to convey massive, crushing emotions. This is why a song like "Heroin" doesn't sound like a typical drug song. It doesn't glamorize it, and it doesn't moralize it. It just is. The tempo speeds up like a heartbeat. The viola screeches. It’s uncomfortable.

Honestly, the music world wasn't ready. When their debut album The Velvet Underground & Nico dropped in 1967—the same year as Sgt. Pepper—it sold almost nothing. Legend has it that Brian Eno once said that while only 30,000 people bought the record, every one of them started a band. It’s a bit of an exaggeration, but the sentiment holds up. Without Lou’s willingness to be ugly, we don't get Joy Division, David Bowie, or R.E.M.

The Warhol Factor

You can’t talk about Lou without Andy Warhol. Andy was the one who saw the potential in this group of misfits playing at the Café Bizarre. He gave them a residency, he gave them a light show (the Exploding Plastic Inevitable), and he gave them Nico.

Lou hated that last part.

Reed was a control freak. Having a German fashion model with a limited vocal range forced into his band was a bitter pill to swallow. Yet, that friction produced "Femme Fatale" and "All Tomorrow's Parties." Warhol acted as a shield, allowing Lou to experiment with feedback and white noise while the rest of the world was busy wearing flowers in their hair. It was a symbiotic relationship built on mutual exploitation and genuine artistic curiosity.

Why the Sound Still Matters Today

The technical side of Lou Reed of The Velvet Underground is often overlooked because people focus so much on the lyrics. But Lou was a gear nerd in his own way. He used "Ostrich tuning," where every string on the guitar is tuned to the same note. It creates this massive, droning wall of sound that feels like a physical weight in the room.

It’s heavy.

✨ Don't miss: BuzzFeed What Harry Potter House Am I In: Why We Still Can’t Stop Taking These Quizzes

Then you have the interplay between Lou and Sterling Morrison. They didn't do "lead" and "rhythm" guitar in the traditional sense. They wove around each other. John Cale brought the avant-garde classical training—the drones and the screeching viola—while Maureen "Moe" Tucker reinvented drumming by standing up and refusing to use cymbals.

- The minimalism was intentional.

- The lack of blues tropes was a choice.

- The feedback was a weapon.

If you listen to White Light/White Heat, it’s basically an assault. The title track is a frantic burst of energy, but "Sister Ray" is seventeen minutes of pure, unadulterated chaos. It was recorded in one take. The engineer allegedly walked out because he couldn't stand the noise. That is the essence of Lou Reed: he pushed until people walked out, and then he pushed a little more.

The Split and the Legacy

By 1970, it was over. Lou walked away from the band at Max’s Kansas City, went back to Long Island, and started working as a typist at his father's tax accounting firm. Can you imagine? The man who wrote "Venus in Furs" sitting in a cubicle for $40 a week.

But the seeds were planted.

When people talk about "punk," they usually think of 1977 London. But the DNA of punk was written in 1966 in a dingy rehearsal space in New York. Lou taught everyone that you didn't need to be a virtuoso. You just needed to have something to say and the guts to say it loudly. He demystified the rock star. He made it accessible to the weirdos and the outcasts.

The Misconceptions About Lou’s Character

It’s easy to paint Lou Reed as a one-dimensional "Prince of Darkness." The leather jackets, the shades, the surly interviews—it was a great act. But if you listen to The Velvet Underground (the self-titled third album), you hear a different side.

Songs like "Pale Blue Eyes" or "Candy Says" are incredibly tender. They show an empathy that the "Sister Ray" version of Lou would never admit to. He cared deeply about the people he wrote about, especially the "misfits" from Warhol’s Factory. He gave them a dignity that society denied them.

He wasn't just documenting the gutter; he was finding the humanity inside of it.

How to Listen Like an Expert

If you want to actually "get" Lou Reed of The Velvet Underground, stop looking for the hooks. Don't treat it like background music. You have to lean into the discomfort.

Start with The Velvet Underground & Nico, but skip the hits for a second. Listen to "The Black Angel's Death Song." It’s abrasive. It’s strange. Then jump to the live recordings at the Matrix in 1969. That’s where you hear the band as a living, breathing organism. They were jamming, stretching songs out, turning pop music into something closer to free jazz or drone music.

Actionable Insights for Musicians and Creators

Lou Reed’s career offers a blueprint that is still incredibly relevant in the age of algorithms and polished social media presence.

- Commit to the Bit: Lou never blinked. Whether he was doing the metal-machine-music thing or the glam-rock thing, he was 100% in. Half-measures don't leave a legacy.

- Embrace the Flaws: The Velvets weren't "tight" in the way a session band is. They were messy. That messiness is where the soul lives. In your own work, stop trying to over-edit the humanity out of what you do.

- Find Your "Schwartz": Every creator needs a mentor or an influence that is outside of their immediate field. Lou took from poets, not just other guitarists. If you want to innovate in your space, look at another space entirely for inspiration.

- Ignore the Initial Reaction: If Lou had listened to the critics in 1967, he would have quit. Most transformative work is hated when it first arrives because it lacks a familiar context. Give your work time to find its audience.

The influence of Lou Reed of The Velvet Underground isn't just a historical footnote. It’s a pulse that still runs through modern indie, post-punk, and even noise music. He proved that you could be smart, literate, and loud all at once. He showed us that the most interesting stories are often the ones people are too afraid to tell.

Go back and put on "I'm Set Free." Listen to the lyrics about being set free to find a new illusion. That was Lou—always moving, always changing, and always brutally honest, even when the truth was something nobody wanted to hear.

To truly appreciate the work, you need to understand that Lou wasn't trying to be "cool." He was trying to be real. In a world of artifice, that’s the most radical thing you can do. Dig into the discography beyond the banana. Look for the bootlegs. Read the lyrics as poetry. The more you look, the more you realize that we’re still just living in the world Lou Reed built in a New York loft over fifty years ago.