You’ve probably felt it. That moment when you’re three hours into a late-night study session or deep into a brutal gym workout, and suddenly, you realize you aren’t actually getting better. You’re just getting tired. You’re putting in the effort, but the results have stalled. This isn't just a "bad day"—it's a fundamental principle of economics and reality. Honestly, understanding the law of diminishing returns meaning is probably the only thing standing between you and burnout.

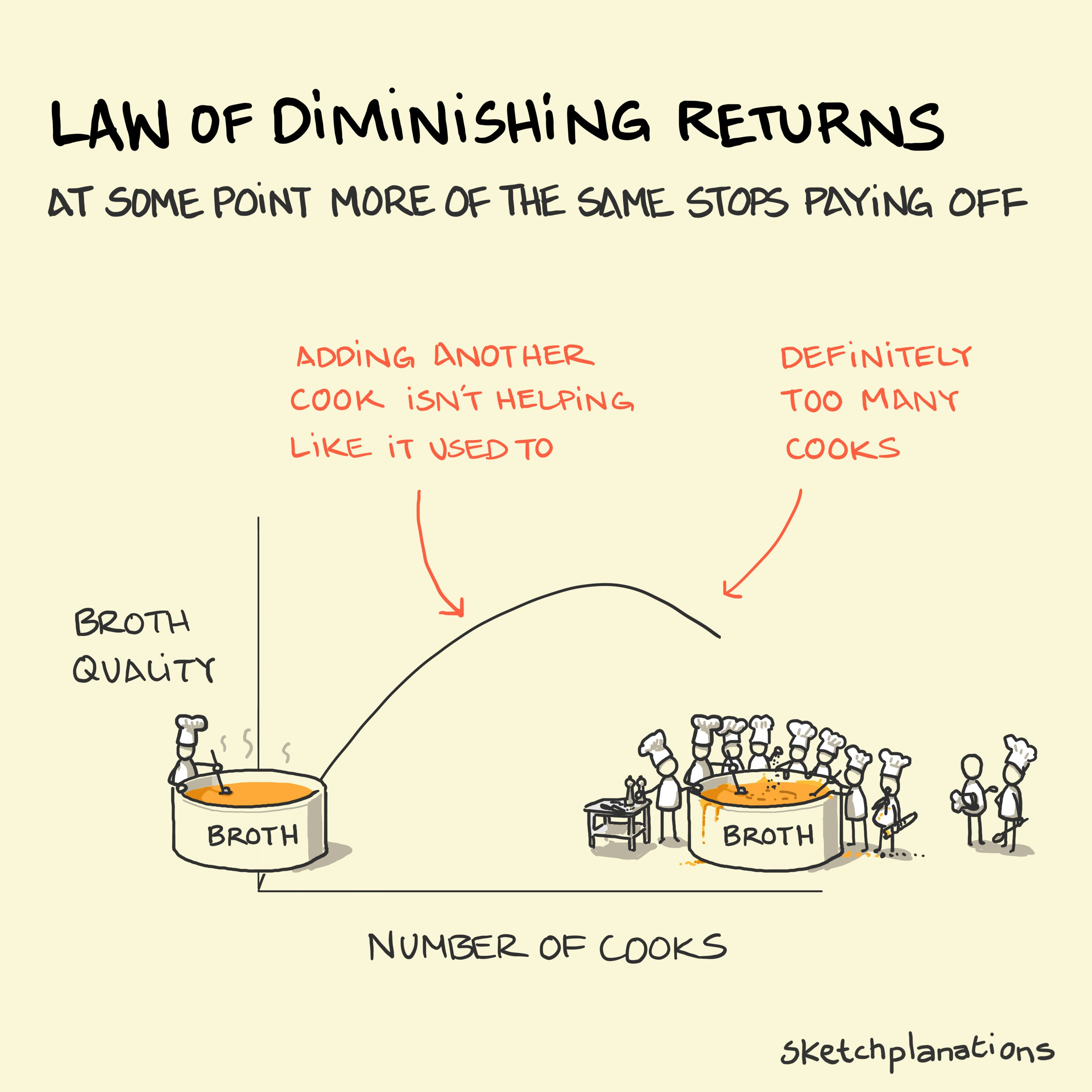

Economics can be dry. Boring, even. But this specific concept is the heartbeat of how businesses fail or fly, and how you manage your own time. At its core, the law of diminishing returns describes a point where adding more of one thing (like labor or fertilizer) to a fixed situation (like a factory or a farm) starts to produce smaller and smaller increases in output. Eventually, if you keep pushing, the returns don't just get smaller—they turn negative. You start breaking things.

🔗 Read more: Russian Money to US Dollars: What Most People Get Wrong

Breaking Down the Law of Diminishing Returns Meaning

Let’s get technical for a second, but keep it real. In formal economic circles, this is often called the Law of Variable Proportions. Imagine you have a small pizza shop. You have one oven. If you’re working alone, you’re slow. You’re taking orders, tossing dough, and cleaning. If you hire a second person, your productivity doubles because one person preps while the other bakes.

That's great. You're winning.

But what happens when you hire ten people for that same tiny kitchen? They start bumping into each other. They’re fighting over the one oven. They’re standing around chatting because there isn’t enough space to work. This is the law of diminishing returns meaning in action: the total output might still be going up slightly, but the "marginal product"—the extra pizza you get from that tenth worker—is way lower than what you got from the second worker.

British economist David Ricardo was one of the first to really dig into this back in the 19th century. He was looking at agriculture. He noticed that as you apply more labor and capital to a fixed piece of land, the additional grain you harvest eventually drops. You can’t just keep throwing seeds at a single acre of dirt and expect an infinite forest of corn. Soil has limits. Space has limits.

The Three Stages You Need to Recognize

It doesn't happen all at once. It’s a slide.

🔗 Read more: Stock Price of MicroStrategy: What Most People Get Wrong

First, you have Increasing Returns. This is the honeymoon phase. Every new hour you spend on a project or every new dollar you invest yields a massive jump in results. You're optimizing. You're finding "low-hanging fruit."

Then comes the Diminishing Returns phase. This is the danger zone. You’re still growing, but it’s harder. You have to work twice as hard to get a 10% improvement. Most people mistake this for a sign that they need to "hustle harder," but usually, it’s a sign that the system is reaching its capacity.

Finally, you hit Negative Returns. This is the "too many cooks in the kitchen" scenario. Adding more input actually makes the total output go down. In a corporate setting, this looks like too many managers creating so much bureaucracy that the actual work stops happening.

Real-World Examples That Aren't From a Textbook

Forget the farm for a minute. Let's talk about things that actually happen in 2026.

Take social media marketing. A brand starts posting once a day on Instagram. Their engagement shoots up. They decide to post five times a day. Engagement per post starts to dip. If they start posting every hour, their followers get annoyed and hit unfollow. That’s a negative return. They spent more money on content and ended up with fewer followers.

📖 Related: When Does No Tax on Tips Go Into Effect? The Reality Behind the Policy

Or look at the world of software development. There’s a famous concept called Brooks’s Law. It states that "adding manpower to a late software project makes it later." Why? Because the amount of time spent on communication and bringing new people up to speed outweighs the actual coding work they contribute. If you have 20 people trying to write the same line of code, you’re essentially paying people to get in each other’s way.

The Saturation of Digital Advertising

In the world of big tech, the law of diminishing returns meaning is a constant ghost in the room. Google and Meta face this with ad placements. There is only so much "screen real estate" a human is willing to tolerate. If they cram an ad into every single pixel, users leave the platform. The marginal benefit of that 50th ad is actually a net loss for the company because it kills the user experience.

- Manufacturing: A factory with 10 machines and 50 workers is efficient. A factory with 10 machines and 500 workers is a safety hazard.

- Education: Studying for 2 hours might get you a B. Studying for 4 hours might get you an A. Studying for 12 hours straight might lead to a mental breakdown where you forget your own name during the exam.

- Health: Working out for 45 minutes builds muscle. Working out for 5 hours straight leads to rhabdomyolysis and a hospital stay.

Why Most People Get This Wrong

The biggest misconception about the law of diminishing returns meaning is that it implies you should stop working. That's not it. It’s about efficiency and allocation.

People often think that if a little bit of something is good, a lot of it must be better. We are conditioned for "more." More growth, more profit, more features. But the law tells us there is an optimal point. In economics, this is where marginal cost equals marginal revenue. Basically, it’s the sweet spot where you’re getting the most "bang for your buck" before things start getting weird.

Another nuance? This law only applies if you keep one factor fixed. If my pizza shop buys a second oven and expands the building, the law resets. We call that "returns to scale." But as long as that kitchen stays the same size, the law is an absolute ceiling. You can't fight math.

The Psychological Toll

We don't talk enough about how this affects our brains. Knowledge workers in 2026 are obsessed with "deep work." But even focus has a diminishing return. Research by people like Anders Ericsson on "deliberate practice" shows that most elite performers can only maintain peak concentration for about four hours a day. Pushing for eight hours doesn't give you double the quality; it usually gives you four hours of great work and four hours of fixing the mistakes you made because you were tired.

How to Outsmart the Curve

So, how do you actually use this information? You don't just sit there and accept that things will get worse. You pivot.

If you’re a business owner and you notice your customer acquisition cost is skyrocketing while your growth is slowing, you’ve hit the diminishing returns of that specific channel. Don't just throw more money at it. That’s a sunk cost fallacy trap. Instead, you change the "fixed factor." You try a new platform, a new product line, or a new technology.

In your personal life, recognize when your "input" is no longer serving you. If you’ve been staring at a document for an hour and haven't written a single sentence, you are in the negative returns phase. Walking away for twenty minutes—changing the environment—is the only way to reset the curve.

Actionable Insights for 2026

- Audit your "More" bias. Look at your current projects. Are you adding more resources just because you don't know what else to do? If the growth isn't proportional to the effort, stop.

- Identify your fixed constraints. Is it time? Space? Energy? Once you know what's fixed, you'll know exactly where the ceiling is.

- Focus on the Marginal. Always ask: "What will one more unit of this actually get me?" If the answer is "not much," reallocate that resource elsewhere.

- Embrace the "Pivot" over the "Push." When returns diminish, it’s usually a signal that the current method has reached its peak. It’s time for a structural change, not more sweat.

The law of diminishing returns meaning isn't a death sentence for your goals. It’s a map. It tells you where the cliff is so you can stop running before you fall off. The most successful people aren't the ones who work the most; they're the ones who know exactly when to stop because they realize that doing more is actually costing them everything.