History is messy. Usually, when we talk about colonial empires, we think of flags, armies, and government bureaucrats. But the story of King Leopold and the Belgian Congo is weirder—and much darker—than that. It wasn't actually a Belgian colony at first. It was a private real estate deal. Imagine a king owning a chunk of land seventy-six times the size of his own country, not as a monarch, but as a CEO. That’s essentially what happened in the late 19th century. Leopold II of Belgium looked at the map of Africa, saw a "magnificent cake" as he called it, and decided he wanted the biggest slice.

He got it.

For twenty-three years, the Congo Free State was his personal fiefdom. Most people today know about the rubber and the severed hands, but the mechanics of how one man tricked the entire world into letting him commit mass murder for profit are often skipped over in history books.

The Great Humanitarian Lie

Leopold was a master of PR. Seriously, the guy could have run a modern tech conglomerate. In 1876, he hosted the Brussels Geographic Conference, inviting famous explorers and dignitaries. He told them he wanted to "civilize" Central Africa, end the East African slave trade, and bring free trade to the region. He formed a front organization called the International African Association. It sounded like a charity.

✨ Don't miss: Why the Hurricane in Florida Tampa Risk is Changing Everything Right Now

It wasn't.

While the world was patting him on the back for his "philanthropy," he hired the explorer Henry Morton Stanley. You've probably heard the famous, though likely apocryphal, "Dr. Livingstone, I presume?" line. That's the guy. Stanley spent years trekking through the Congo basin, tricking local chiefs into signing over their land for pieces of cloth or trinkets. These "treaties" gave Leopold absolute power.

At the Berlin Conference of 1884-1885, the European powers basically said, "Sure, Leopold, you can have the Congo." They thought he’d keep it open for everyone to trade. They were wrong. He locked it down. He created the Force Publique, a brutal mercenary army, to enforce his will.

The Red Rubber Terror

Initially, Leopold was going broke. He spent a fortune on infrastructure and his army. But then, the world changed. The invention of the pneumatic tire by John Boyd Dunlop in 1888 created an insatiable global demand for rubber.

The Congo was full of wild rubber vines.

This is where the horror of the King Leopold Belgian Congo era really peaks. Leopold didn't build plantations. That would have taken too long. Instead, his agents would march into a village and kidnap the women. They’d hold them hostage until the men went into the jungle to meet impossible rubber quotas. If the men didn't bring back enough? The punishments were psychotic.

We’ve all seen the photos. The most haunting one shows a man named Nsala sitting on a porch, staring at the severed hand and foot of his five-year-old daughter. This wasn't just random cruelty; it was a management system. The Force Publique soldiers were required to account for every bullet they fired. To prove they hadn't "wasted" ammunition on hunting or mutiny, they had to bring back the severed right hand of anyone they killed. Sometimes, if they missed a shot or used a bullet for food, they would just cut the hand off a living person to balance their books.

Adam Hochschild and the Numbers Game

If you want to understand the scale of this, you have to look at the work of historian Adam Hochschild, author of King Leopold’s Ghost. He estimates that roughly 10 million people died during this period.

Ten million.

Some historians argue over the exact number, mainly because there wasn't a census in the jungle in 1890. Critics of the 10 million figure, like Jean-Stengers, suggest it might be lower, but even the most "conservative" estimates are in the millions. Most didn't die from direct execution. They died from exhaustion, starvation (because they couldn't tend their crops while hunting rubber), and imported diseases like smallpox and sleeping sickness. The birth rate plummeted. People fled into the deep forest, where they couldn't survive. It was a total societal collapse.

The Whistleblowers: Morel and Casement

The world eventually found out, but not because of governments. It was because of a shipping clerk named E.D. Morel. He worked for a company in Liverpool that handled the Congo trade. He noticed something suspicious on the docks. Ships were coming from the Congo filled with valuable rubber and ivory. But when they went back? They were only carrying soldiers, guns, and ammunition.

No trade goods. No "civilizing" supplies.

Morel realized the Congo was a slave state. He teamed up with Roger Casement, a British consul who traveled into the interior to document the atrocities. Their work led to the first great human rights movement of the 20th century. Mark Twain wrote a scathing satire called King Leopold's Soliloquy. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote The Crime of the Congo.

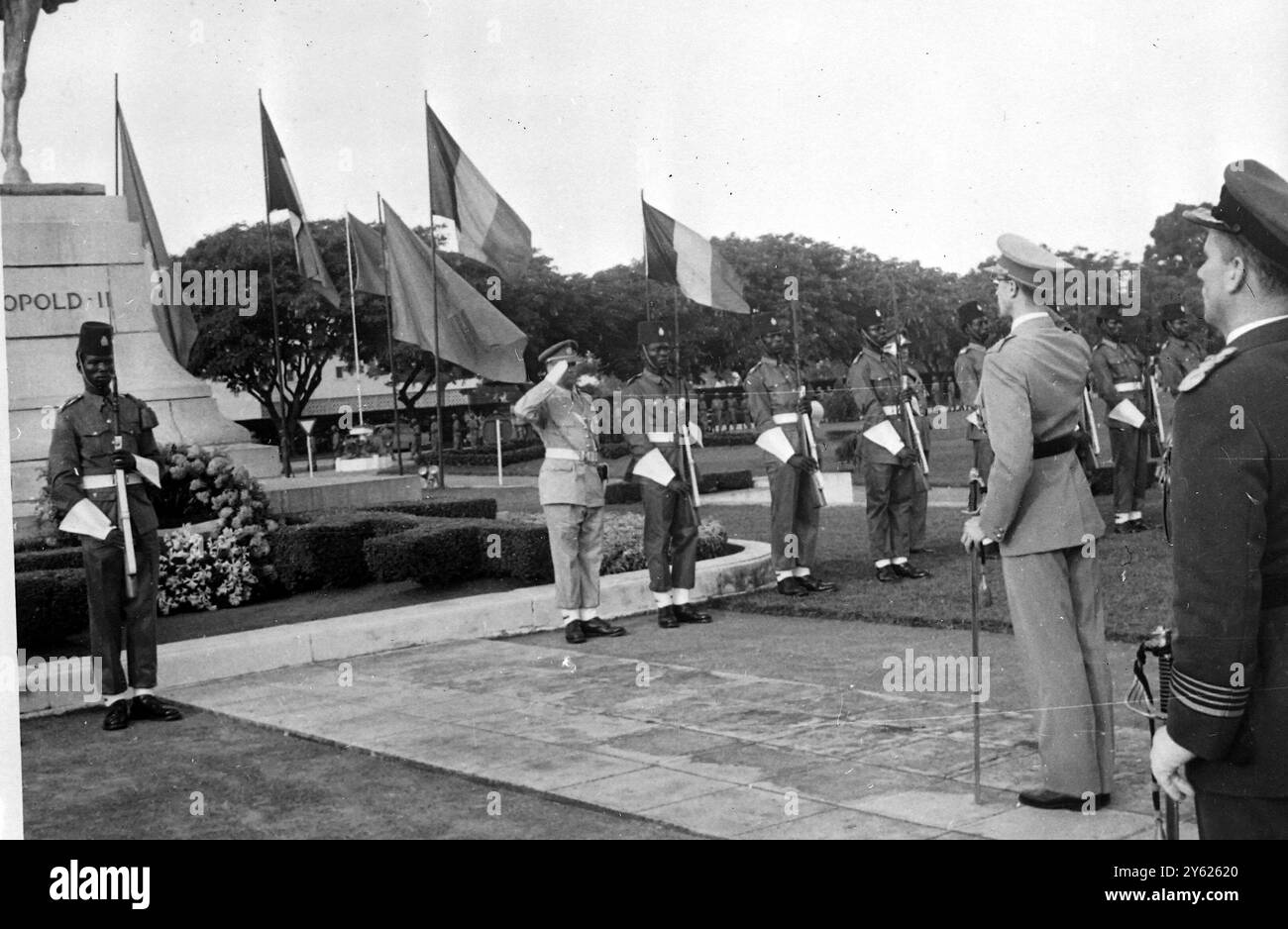

By 1908, the international pressure was too much. The Belgian Parliament forced Leopold to hand over the Congo to the Belgian state. It became the Belgian Congo.

👉 See also: Why the Twin Towers South Tower Collapse Still Haunts Structural Engineering

Did things get better? Kinda. The systemic mutilations stopped. But the forced labor continued for decades. The "Belgian" part of the name didn't mean freedom; it just meant the exploitation was now managed by a government rather than one guy's private company.

Why This Still Matters in 2026

The scars are still there. You can't just delete half a population and expect a region to be "fine" a century later. When the Congo finally gained independence in 1960, the Belgians left behind a country with almost no university graduates and a totally hollowed-out infrastructure.

The chaos that followed—the rise of Mobutu Sese Seko, the mining of cobalt and coltan that powers your smartphone today—is directly linked to the extractive systems Leopold built. He treated the land like a mine, not a country.

Actionable Steps for Deeper Understanding

If you're looking to actually grasp the weight of this history beyond a quick article, here is how you should approach it:

🔗 Read more: Earthquake in Truckee California: What Locals Usually Get Wrong About the Faults

- Read the Source Material: Don't just take a summary's word for it. Look up the Casement Report (1904). It’s a dry, bureaucratic document that is somehow more terrifying than any movie because of its clinical detail of the violence.

- Trace the Economics: Look into the "Union Minière du Haut-Katanga." This was the company that took over after Leopold. Understanding how they transitioned from rubber to minerals like uranium (the Congo supplied the uranium for the Hiroshima bomb) explains the modern geopolitical interest in the region.

- Visit the Tervuren Museum: If you're ever in Brussels, visit the Royal Museum for Central Africa. It was originally built by Leopold to showcase his "spoils." It’s recently been "decolonized" and renovated to address the atrocities, and it's a fascinating look at how a nation tries to reckon with a monstrous past.

- Support Local Voices: Follow Congolese historians and journalists like Kambale Musavuli. History is too often told by the people who stayed in Europe; hearing the perspective of those living with the legacy of the King Leopold Belgian Congo era is vital for a balanced view.

The reality is that Leopold’s "Free State" was neither free nor a state. It was a heist. Understanding that distinction is the only way to make sense of the modern Democratic Republic of the Congo. It wasn't "tribalism" or "bad luck" that broke the region; it was a deliberate, profit-driven system designed to break humans. We are still watching the pieces try to come back together.

---