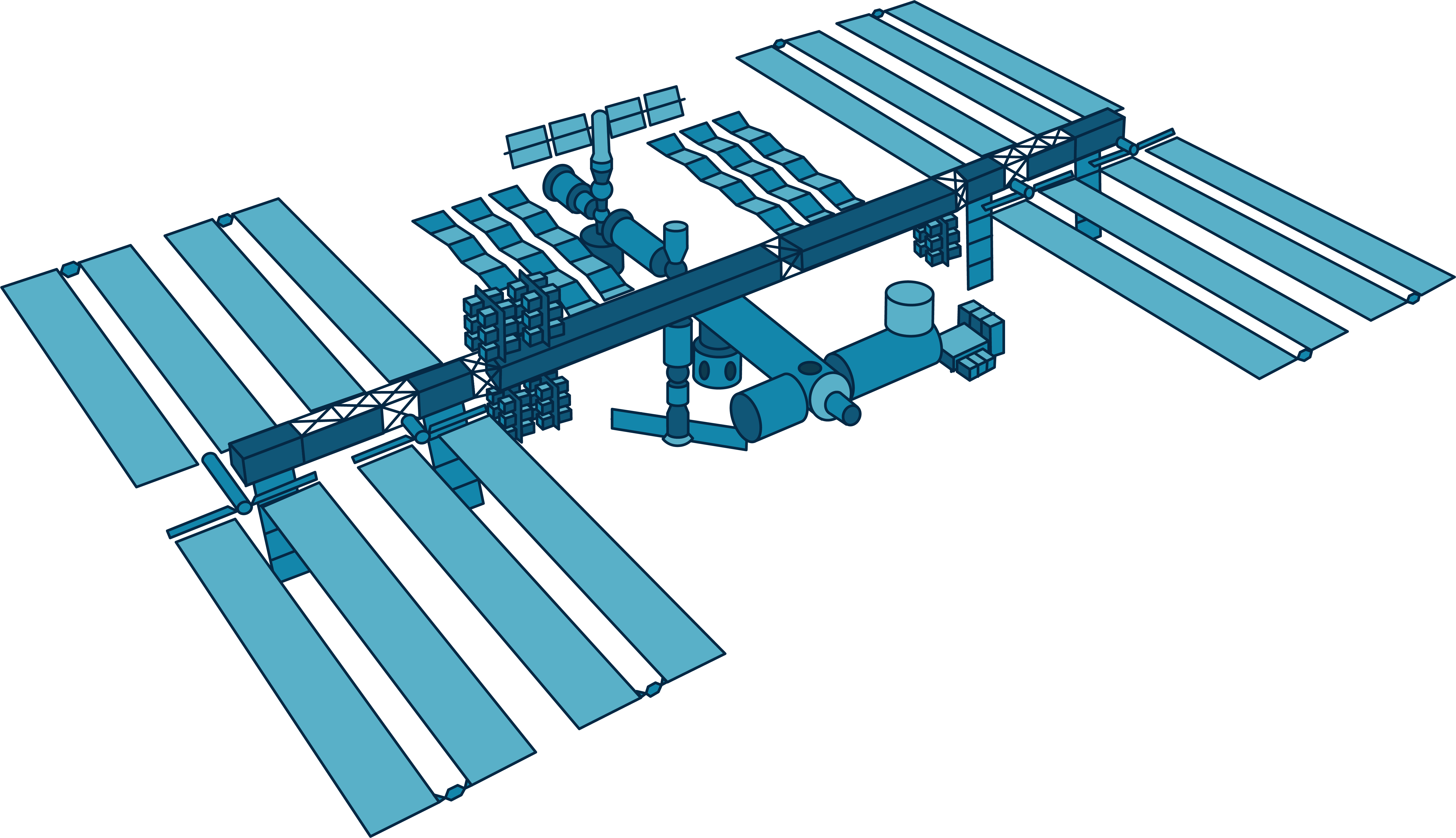

You’ve probably seen the "Blue Marble" or that famous shot of the sun rising over the limb of the Earth. Those are fine. But honestly, most of the international space station pictures that go viral on social media are barely scratching the surface of what’s actually being captured 250 miles up. It’s kinda wild when you think about it. We have a football-field-sized laboratory screaming through the vacuum at 17,500 miles per hour, and yet we mostly just look at the same blurry city lights over and over.

The reality is much gritier. And way more interesting.

The gear behind those international space station pictures

NASA doesn't just use "space cameras." That’s a common misconception. They use off-the-shelf Nikon DSLRs. For real. If you walked into the Cupola—that seven-windowed observation module—you’d see a bunch of Nikon D5s and D6s floating around, usually tethered with Velcro so they don't drift into a control panel. They use massive 800mm or even 1200mm lenses. Imagine trying to hold a lens that heavy while you're weightless, tracking a target on the ground that's disappearing over the horizon in seconds. It’s like trying to photograph a speeding bullet from the back of a moving motorcycle, except the motorcycle is in orbit.

Why lighting is a total nightmare

In space, there is no atmosphere to scatter light. On Earth, we have the "golden hour." In orbit, the light is either blindingly harsh or pitch black. When an astronaut takes international space station pictures of a spacewalk, the sun-side of the suit is blown out (pure white), while the shadow side is a literal void.

Don Pettit, an astronaut known for his incredible orbital photography, figured out how to hack this. He actually built a "barn door tracker" out of spare parts on the ISS to compensate for the station's movement. This allowed him to take long-exposure shots of city lights without them turning into long, blurry streaks. Without that kind of MacGyver-level engineering, we wouldn’t have those sharp, spider-web images of London or Tokyo at night.

👉 See also: Pi Coin Price in USD: Why Most Predictions Are Completely Wrong

What the "Blue Marble" misses

Everyone loves the view of the Caribbean. The turquoise water against the deep black of space is a classic. But the really valuable international space station pictures are the ones that document change. Scientists use these photos to track things that satellites sometimes miss.

Satellites are great because they follow a fixed "sun-synchronous" orbit. They see the same spot at the same time every day. But the ISS has a "precessing" orbit. This means it passes over different spots at different times of the day. One day it might see the Amazon at noon; a week later, it’s seeing it at dawn. This gives us a 3D-like understanding of how shadows and light affect our view of deforestation or glacial melt. It's not just pretty; it's data.

The Aurora problem

People think the Aurora Borealis looks like a neon green curtain from space. It does, mostly. But through the lens of a camera on the ISS, it’s often a deep, blood red. This happens because the station is actually flying through the aurora. Most people don't realize that. You’re not looking at it from below; you’re looking through the soup of charged particles hitting the upper atmosphere.

How to find the raw files (The stuff NASA doesn't tweet)

If you’re only looking at NASA’s Instagram, you’re seeing the "greatest hits." They’re color-corrected and cropped. To see the real stuff, you have to go to the Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth. It’s a massive database maintained by the Johnson Space Center.

✨ Don't miss: Oculus Rift: Why the Headset That Started It All Still Matters in 2026

There are over 3.5 million images there. Most are boring. You’ll find thousands of shots of clouds that look like white noise. But then, you’ll find a frame where the light hits the Andes just right, or a shot of a volcanic plume that hasn't been shared by a single news outlet yet. It’s a rabbit hole. You start looking for your hometown and end up staring at the salt flats in Bolivia for three hours.

The "Nadir" perspective

Most international space station pictures are taken at an oblique angle. That’s what gives them that "epic" feel. However, "Nadir" photography—looking straight down—is where the real detail lives. When the station is directly over a city, the lack of atmospheric distortion allows for incredible clarity. You can see individual cargo ships in the Suez Canal. You can see the circular patterns of center-pivot irrigation in the middle of the desert.

Debunking the "CGI" claims

Let's address the elephant in the room. There’s a segment of the internet that thinks every photo from the ISS is fake. Their main argument? "Where are the stars?"

It’s a basic photography thing. If you’re taking a picture of a brightly lit Earth or a white spacesuit, your camera's shutter is only open for a fraction of a second. Stars are faint. To capture them, you need a long exposure. If you leave the shutter open long enough to see stars, the Earth becomes a giant, glowing white blob. It’s the same reason you don't see stars in your backyard photos at night if the porch light is on. Physics doesn't care about conspiracy theories.

🔗 Read more: New Update for iPhone Emojis Explained: Why the Pickle and Meteor are Just the Start

Taking your own "Space" photos from home

You can’t go to the ISS (probably). But you can actually influence what cameras on the station capture. There’s a program called Sally Ride EarthKAM. It’s primarily for students, but it allows people to request specific images of Earth from a dedicated camera on the ISS. When the station passes over your requested coordinates, the camera clicks.

It’s a weirdly personal way to interact with a multi-billion dollar satellite. Instead of just looking at "international space station pictures," you're looking at your picture.

The future of orbital imagery

We are moving away from just "photos." The ISS is now equipped with hyperspectral imagers. These aren't cameras in the traditional sense. They "see" in hundreds of different wavelengths of light. They can tell the difference between a healthy forest and one that’s stressed by drought before the leaves even turn brown.

The next step isn't just higher resolution. We’ve already got plenty of pixels. The next step is "near real-time" access. We’re getting to a point where the delay between a photo being taken and it appearing on a server on Earth is shrinking to minutes.

Actionable Next Steps for Enthusiasts

- Visit the Source: Skip the social media aggregators. Go directly to the Gateway to Astronaut Photography of Earth. Use the "Search Photos" tool to find your specific city.

- Check the Metadata: If you download a raw file, look at the EXIF data. It will tell you the exact lens, focal length, and ISO the astronaut used. It’s a masterclass in high-speed, low-light photography.

- Track the Station: Use an app like "ISS Detector." If you know when the station is overhead, you can correlate your own ground-based photos of the station with the photos the astronauts might be taking of your region at that exact second.

- Follow the Crew: Individual astronauts often post "unofficial" shots on their personal accounts that don't make it to the main NASA feed. These are usually the most candid and technically interesting ones.

The ISS won't be up there forever. Current plans have it de-orbiting around 2030. That means we have a limited window left to capture this specific perspective of our planet before the era of the "Grand Laboratory" ends and we move on to smaller, commercial stations. Look at the pictures now while the Cupola is still open.