Ask a random person on the street who made the computer and you’ll probably hear one of three names: Steve Jobs, Bill Gates, or maybe Alan Turing if they’ve seen The Imitation Game. Honestly? They’re all wrong. Or at least, they're only seeing a tiny sliver of a massive, messy, centuries-long puzzle.

The computer wasn't "invented" in a garage in the 70s. It didn't pop into existence because of a single "Eureka!" moment. It was a slow, agonizing evolution involving 19th-century weavers, Victorian mathematicians, code-breaking geniuses during World War II, and a whole lot of government funding that nobody likes to talk about. To find out who made the computer, you have to look past the Silicon Valley marketing and go back to a time when a "computer" was actually a job title for a person—usually a woman—who sat at a desk and did long-division all day.

The Victorian Blueprint: Babbage and Lovelace

Before there were microchips, there were gears. Heavy, clanking, brass gears. Charles Babbage is the guy most historians point to when they talk about the "father" of computing. In the 1820s, he got tired of seeing humans make mistakes in mathematical tables used for navigation. Humans are bored easily. We're prone to typos. Babbage wanted a machine that could crunch numbers perfectly every time.

He designed the Difference Engine, which was basically a giant calculator. But then he got more ambitious. He started sketching out the Analytical Engine. This is where things get interesting. This thing wasn't just a calculator; it was a general-purpose machine. It had memory (he called it the "store") and a central processor (the "mill"). It even used punch cards, an idea he borrowed from the Jacquard loom used in textile factories.

But Babbage never actually finished building it. He ran out of money and drove the British government crazy with his constant redesigns.

Enter Ada Lovelace. She was the daughter of the poet Lord Byron, but she was a math prodigy. While Babbage was obsessed with the hardware, Lovelace saw the soul of the machine. She realized that if the machine could manipulate numbers, it could also manipulate anything that represented those numbers—like music or letters. She wrote what is widely considered the first computer program: an algorithm intended to be processed by the Analytical Engine to calculate Bernoulli numbers.

She saw the future. Babbage saw a better calculator. Without her vision, the computer might have remained a niche tool for engineers for another century.

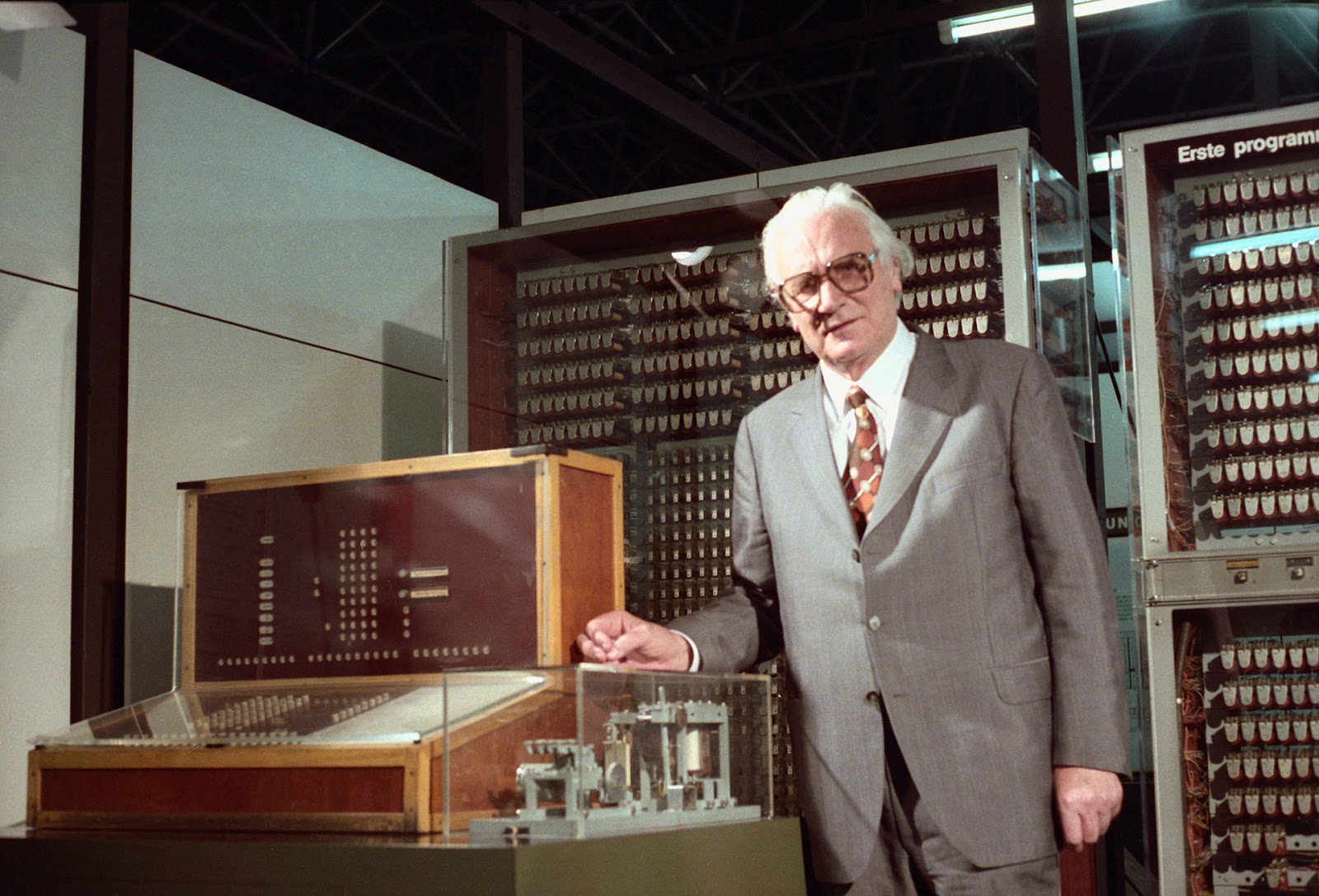

The Giant Vacuum Tubes of World War II

Fast forward about a hundred years. The world is at war, and the military needs two things: a way to crack enemy codes and a way to calculate artillery firing tables. This is when the modern computer really started to take shape, and it happened on both sides of the Atlantic simultaneously.

💡 You might also like: Why the Milwaukee Charger M12 M18 is Still the King of the Jobsite

In England, you had Alan Turing. Most people know him for breaking the Enigma code at Bletchley Park. He developed the "Turing Machine" concept, a theoretical model that defines what a computer actually is. His "Bombe" machine was a mechanical beast that sifted through millions of German code combinations. But even Turing didn't "make" the first digital computer alone. Tommy Flowers, a post office engineer, built Colossus—the world's first programmable, electronic, digital computer—specifically to crack the High Command's Lorenz cipher.

Meanwhile, in the United States, things were getting big. Really big.

The ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer) was built at the University of Pennsylvania by John Mauchly and J. Presper Eckert. It was a monster. It weighed 30 tons. It took up 1,800 square feet. It used 18,000 vacuum tubes. Legend says that when they turned it on, the lights in Philadelphia dimmed.

But here’s the kicker: Mauchly and Eckert get all the credit, but the actual "programming" was done by six women: Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Marlyn Wescoff, Ruth Lichterman, Elizabeth Bilas, and Jean Bartik. They didn't have keyboards or screens. They had to physically wire the machine, plugging and unplugging cables to tell it what to do. For decades, they were cropped out of the photos or dismissed as "refrigerators ladies"—basically models posing with the machine.

They were the ones who made it work.

The Transistor: Why Your Phone Isn't the Size of a House

If we were still using vacuum tubes, your smartphone would be several miles wide. The shift from "giant room-sized heater" to "portable device" happened because of the transistor.

In 1947, John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, and William Shockley at Bell Labs invented the transistor. It did the same job as a vacuum tube—switching and amplifying electronic signals—but it was tiny, reliable, and didn't burn out every twenty minutes. This is the moment the computer became a commercial product rather than a military secret.

This led to the "Silicon" in Silicon Valley. Robert Noyce and Jack Kilby (working separately) figured out how to cram multiple transistors onto a single chip of silicon. This became the Integrated Circuit. Without this, there is no Apple, no Microsoft, and no internet.

The Personal Computer Revolution

By the 1970s, the "Who" behind the computer shifts from government-funded scientists to hobbyists in Northern California. The Homebrew Computer Club was where the magic happened. Steve Wozniak, a guy who just wanted to build a cool machine to impress his friends, designed the Apple I. Steve Jobs, the guy with the vision, saw it and realized people might actually want to buy one.

But even then, they weren't the first. The MITS Altair 8800 beat them to it in 1975. It didn't even have a screen or a keyboard—just switches and lights—but it was the spark that started the fire. Bill Gates and Paul Allen saw the Altair and decided to write a version of the BASIC programming language for it. That was the birth of Microsoft.

It’s easy to credit the "Two Steves" or Gates, but they were standing on a mountain of research provided by Xerox PARC. Most people don't realize that Xerox (the copier company) actually invented the modern computer experience. They created the Alto in 1973, which had a mouse, a graphical interface (windows and icons), and even Ethernet. They just didn't know what to do with it. Jobs visited PARC, saw the future, and basically "borrowed" the ideas for the Macintosh.

What Most People Get Wrong

The biggest misconception is that there is a single "inventor." If you look at the patent lawsuits of the 1970s, it gets even more complicated. In 1973, a judge actually invalidated the ENIAC patent, ruling that Mauchly and Eckert had "derived" the idea from John Vincent Atanasoff, a professor at Iowa State who built the ABC (Atanasoff-Berry Computer) in the late 30s.

So, was it Atanasoff? Was it Babbage? Was it the women of the ENIAC?

The truth is that who made the computer is a collective "we." It was a relay race where the baton was passed over 200 years.

Key Figures in the Creation of the Computer

- Charles Babbage: Designed the first mechanical general-purpose computer (the Analytical Engine).

- Ada Lovelace: Wrote the first algorithm and envisioned computers doing more than math.

- Alan Turing: Provided the mathematical foundation for how all modern computers process information.

- John Mauchly & J. Presper Eckert: Built the ENIAC, the first large-scale general-purpose electronic computer.

- The ENIAC Six: The women who actually programmed the first electronic computer.

- John von Neumann: Developed the "stored-program" architecture that almost every computer uses today.

- John Bardeen, Walter Brattain, & William Shockley: Invented the transistor, making computers small and efficient.

- Douglas Engelbart: Invented the mouse and the concept of "windows" long before Apple or Microsoft.

Real-World Impact and Nuance

When we talk about who made the computer, we also have to talk about the materials. The physical reality of a computer today relies on the extraction of rare earth minerals and the massive manufacturing infrastructure in East Asia. The "maker" isn't just the person with the patent; it's the global supply chain that turned a 30-ton room of tubes into a piece of glass in your pocket.

We also have to acknowledge the dark side. Much of early computing was driven by the need to calculate more efficient ways to kill people—ballistics for bombs and encryption for secret messages. The computer is a tool born of conflict.

📖 Related: How to Change Date on MacBook: What Most People Get Wrong

Actionable Insights for the Tech-Curious

Understanding the history of who made the computer isn't just for trivia night. It changes how you view technology today.

- Look for the "Software" in the Hardware: Just as Ada Lovelace saw beyond Babbage's gears, look at how modern AI is currently the "software" redefining our current hardware. History repeats.

- Support Open Innovation: Many of the biggest breakthroughs (like the internet and the early personal computer) happened because people shared ideas in clubs or through government-funded research.

- Acknowledge the Hidden Figures: In your own work or studies, remember that the "face" of a project is rarely the only one who made it happen. The "programmers" of the ENIAC were ignored for 50 years; don't make that mistake with your own teams.

- Understand the "Von Neumann Architecture": If you're a student or developer, look into why we still use the basic layout designed in the 1940s. It helps explain why your RAM matters just as much as your CPU.

The computer is a human achievement. It wasn't one guy in a turtleneck. It was a centuries-long chain of dreamers, mathematicians, and engineers who all contributed a single gear or a single line of code to the most important machine ever built.