It’s just a big, dead rock, right? That’s what we used to think. For decades, the consensus was that the Moon was a cold, inert lump of basalt and dust—basically a fossil of the early solar system. But honestly, the inside of the moon is way weirder than that. Recent data from NASA’s GRAIL mission and re-analyzed Apollo-era seismic charts show a world that is far from "dead." We’re talking about a layered complexity that looks less like a billiard ball and more like a giant, partially melted jawbreaker.

The Core Problem

For a long time, scientists couldn't agree if the Moon even had a core. It’s small. Compared to Earth, it lacks a strong magnetic field. So, the logic went: no field, no liquid core. But we were wrong.

In 2011, Renee Weber and her team at NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center used state-of-the-art seismology to look at the old Apollo data. They found that the Moon has a solid, iron-rich inner core. It's about 150 miles in diameter. That's wrapped in a fluid outer core, mostly liquid iron, and then—here’s the kicker—a partially melted boundary layer. This "mushy" zone is a game-changer. It explains why the Moon still flexes and "breathes" due to Earth's gravity. It’s not a static object; it’s a body under constant tidal stress.

Why the Core Matters for Us

If you're planning on living there—which NASA’s Artemis program is basically betting on—the core's state matters. It tells us about the Moon's history. It tells us why the magnetic field vanished 4 billion years ago. Without that field, the surface got blasted by solar wind. That's why the inside of the moon is the only place where the "pristine" history of our neighborhood is actually preserved.

The Mantle is Not What You Think

Above that core sits the mantle. It’s massive. It makes up the bulk of the Moon’s volume. If you could slice it open, it wouldn't look like Earth's red-hot magma. It’s mostly solid rock like olivine and pyroxene. But it’s "unbalanced."

🔗 Read more: How a Concave Lens Ray Diagram Actually Works (and why it's always smaller)

The Moon is lopsided. This is a weird fact that sounds fake but is 100% true. The crust on the "far side" (the side we never see) is much thicker than the crust on the "near side." Why? Because when the Moon was a ball of fire 4.5 billion years ago, the Earth was also a molten mess. The Earth radiated heat onto the near side of the Moon, keeping it liquid longer. Meanwhile, the far side cooled and thickened.

This created a "chemical asymmetry." The near side is covered in "Maria"—those dark spots you see at night. Those are ancient volcanic plains where the thinner crust allowed the inside of the moon to bleed out onto the surface.

The Mystery of the Low-Density Zones

In 2023, researchers using data from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) started talking about "lunar mass concentrations" or mascons. These are spots where the gravity is unexpectedly strong. They're basically giant, heavy "plugs" of dense mantle material that rose up into the crust during massive asteroid impacts.

But there are also "voids." Not "alien base" voids—let's be clear—but highly porous regions. The top 10 to 20 kilometers of the Moon are incredibly smashed up. Billions of years of meteorites have turned the upper crust into something called "regolith" and "megaregolith." It's like a giant, dusty sponge. This porosity is why the Moon "rings like a bell."

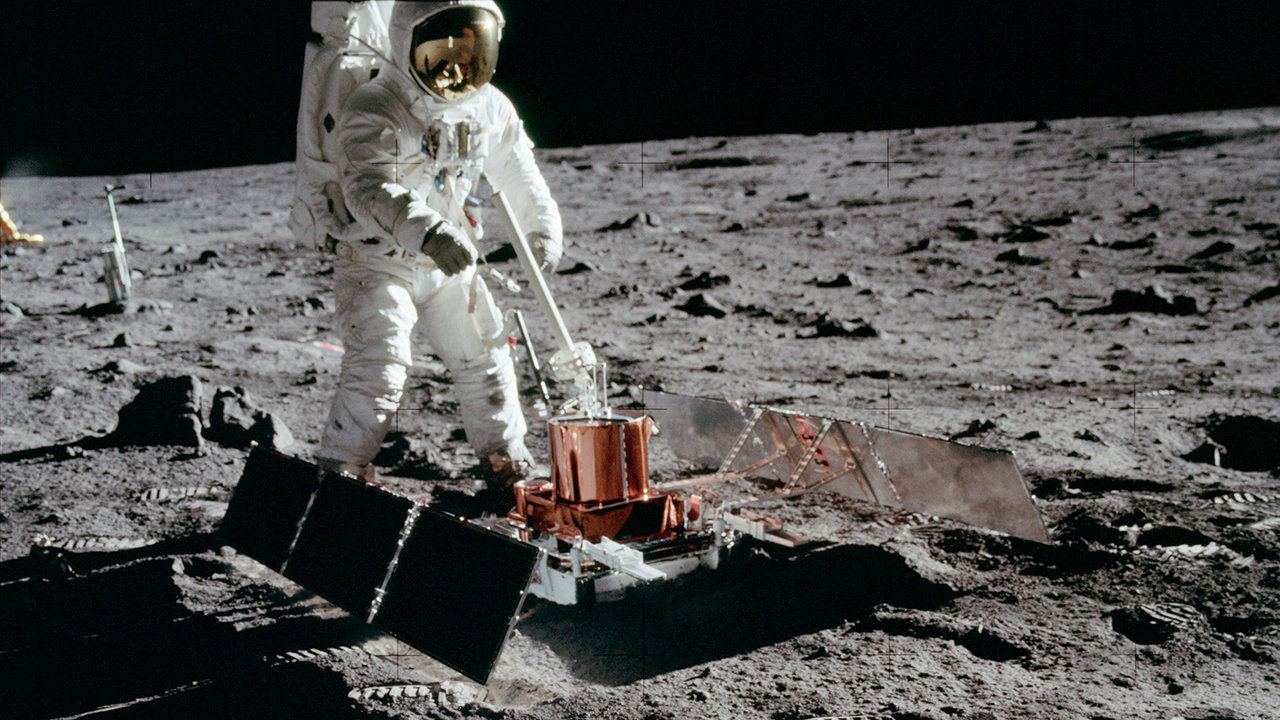

The Apollo 12 Experiment

When the Apollo 12 lunar module's ascent stage was crashed back into the Moon, the seismic vibrations lasted for over an hour. On Earth, that would never happen. The water in our rocks dampens vibrations. But the inside of the moon is bone-dry and fractured. The vibrations just bounce around in that shattered crust like echoes in a cathedral. It’s eerie.

Is There Still Volcanism?

Wait. If the core is partially liquid, is there still lava?

Sorta. Probably not the way you’re thinking. You won’t see a glowing red cone on the horizon. But in 2014, the LRO spotted "Irregular Mare Patches." These are smooth, weirdly shaped areas that look like they're less than 100 million years old. In geologic time, that’s yesterday. It suggests that the inside of the moon might still be "burping" out small amounts of volcanic gases or heat.

The heat isn't coming from the birth of the solar system anymore. It’s coming from radioactive decay. Elements like Thorium and Potassium are buried deep down there. They decay, they get hot, and they keep the lunar interior from totally freezing solid.

The Search for Water Ice

This is the big one. This is why we’re going back. We used to think the Moon was drier than the Sahara. Then we looked in the shadows.

Deep in the polar craters, where the sun never shines, it's cold. Really cold. Like -400 degrees Fahrenheit. Because the Moon’s tilt is so slight, these craters stay in permanent darkness. We’ve found evidence of "volatiles"—water ice—trapped in the soil.

But the real question is: is there water inside?

Analysis of "orange soil" brought back by Apollo 17 (Harrison Schmitt found it, he was the only geologist to walk on the Moon) showed tiny glass beads. These beads had water molecules trapped inside them. This means that at some point, the inside of the moon had a surprising amount of water. If that water is still down there in the form of hydrated minerals, it changes everything for future colonies. We wouldn't just be mining the surface; we'd be "mining" the interior's history.

Practical Steps for the "Lunar Literate"

If you're following the news on lunar exploration, don't just look at the rocket launches. The real science is happening in the data. Here is how to stay ahead of the curve:

- Follow the VIPER Mission: NASA is sending a rover to literally drill into the Moon’s South Pole to see how deep the "wet" layers go. This will confirm if the interior is a viable resource.

- Track Seismic Data: Organizations like the Lunar and Planetary Institute (LPI) frequently release new interpretations of "Moonquake" data. These quakes are caused by Earth's gravity "tugging" on the Moon's interior layers.

- Look at Lunar Swirls: These are weird, wavy patterns on the surface. They’re tied to localized magnetic fields buried in the crust—basically "ghosts" of the Moon's ancient core.

The inside of the moon is basically a time capsule. Because the Moon lacks plate tectonics, it hasn't "recycled" its interior the way Earth has. Every layer, every "mushy" zone, and every iron-rich plug is a record of what happened 4 billion years ago. When we study the lunar interior, we aren't just looking at a rock. We're looking at the blueprint of how planets are made.

📖 Related: Why Use a Phone Number for Information on Telephone Systems When You Could Just Google It?

It’s not just a dusty orb. It’s a complex, stratified, and surprisingly active world that is only now starting to give up its secrets.

Actionable Insight: If you want to visualize this yourself, download the "LROC QuickMap." It’s a free tool provided by Arizona State University that lets you overlay gravity maps (showing the interior density) over the visual surface of the Moon. You can literally see where the heavy interior has "leaked" upward.