Light is weird. Seriously. One minute it’s acting like a wave, and the next, it’s hitting a piece of glass and bouncing off in directions that seem totally random until you sit down and draw a concave lens ray diagram. If you’ve ever looked through a pair of glasses meant for nearsightedness, you’ve seen this physics in action. Everything looks tiny. It’s crisp, sure, but it’s definitely shrunken down.

Physics teachers love to make this sound like some ancient, mystical secret. Honestly? It’s just geometry. A concave lens is basically a "diverging" lens. It’s thinner in the middle than at the edges. When parallel light rays hit that curved surface, they don't want to meet up for coffee. They run away from each other. But if you're trying to pass a physics exam or just understand how your doorbell camera works, you need to know exactly where those rays think they’re going.

The Geometry of Divergence

Most people get confused because they try to treat every lens like a magnifying glass. Big mistake. A convex lens brings light together to a point, creating those cool "burn a leaf" focal spots. But the concave lens? It does the opposite.

When you draw a concave lens ray diagram, you're tracking how light bends (refracts) as it moves from air into glass and back into air. Because the lens curves inward—sorta like a cave, which is an easy way to remember the name—the light rays spread out. If you follow those spreading rays backward with your eyes, they seem to be coming from a single spot in front of the lens. That’s your virtual focus.

Why the "Virtual" Image Matters

In the world of optics, "virtual" isn't about VR headsets or Minecraft. It just means the light rays don't actually cross at that point. They only look like they do.

If you put a piece of paper where a virtual image is supposed to be, you won’t see anything projected on it. It’s a ghost image. This is why every single concave lens ray diagram you will ever draw results in an image that is virtual, erect (upright), and diminished (smaller). It doesn’t matter if the object is an inch away or a mile away. The result is always the same shrunken version of reality.

Think about a peephole in a door. You look through it, and the person standing outside looks like a tiny version of themselves. That’s a concave lens doing its job. It’s cramming a wide field of view into a small space so you can see if it’s the delivery driver or a sketchy solicitor.

Drawing the Rays: The Non-Negotiables

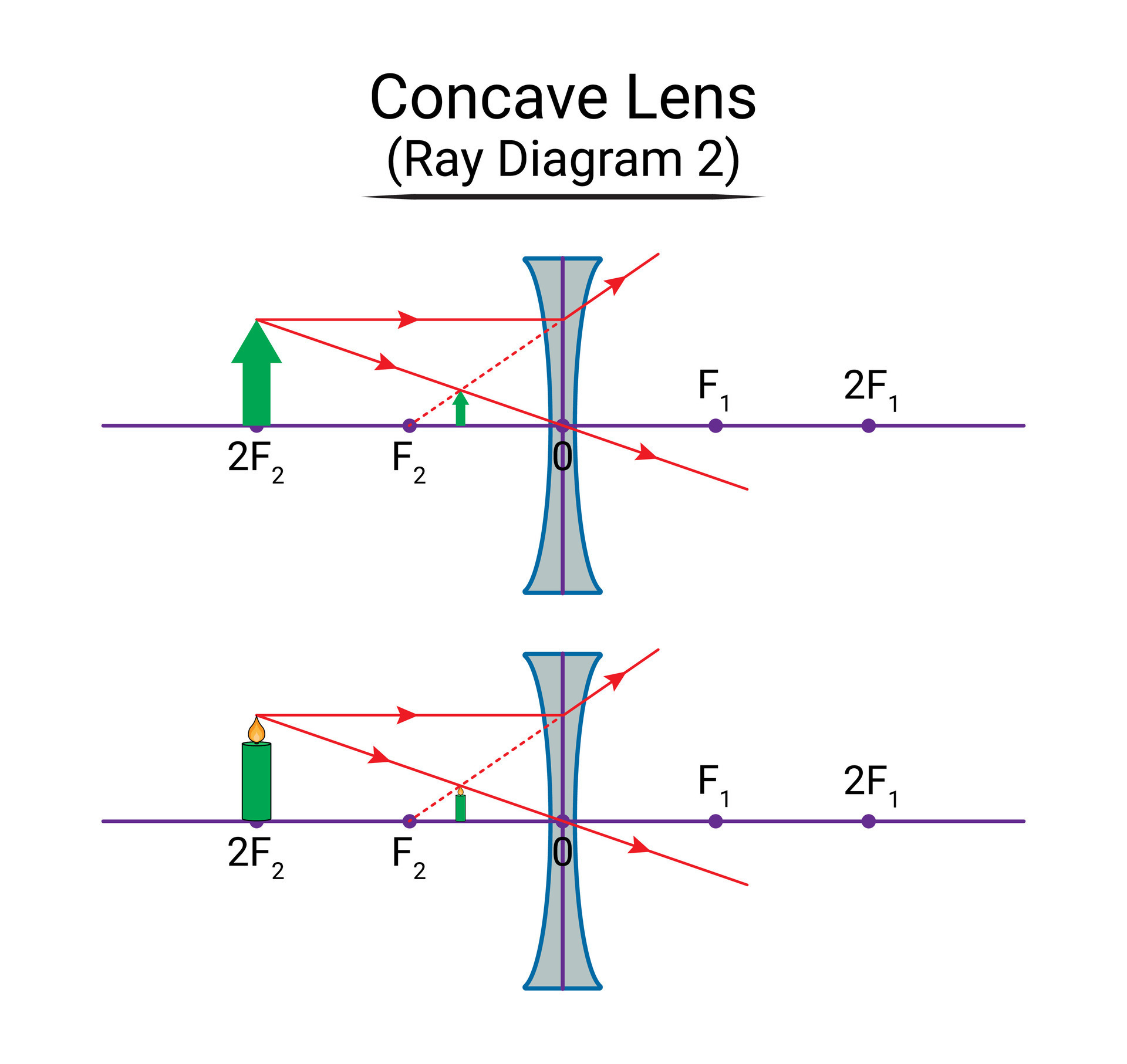

You don't need to be an artist. You just need a ruler. When you start your concave lens ray diagram, you generally track three specific rays.

- The Parallel Ray: This one starts at the top of your object and travels perfectly flat, parallel to the principal axis. Once it hits the lens, it bends upward. But here’s the trick: it bends in a direct line away from the focal point on the front side of the lens.

- The Center Ray: This is the easiest one. It goes straight through the very middle of the lens (the optical center). It doesn't bend at all. It just keeps going in a straight line.

- The Focal Ray: This one is aimed at the focal point on the far side of the lens. Before it can get there, the lens grabs it and bends it so it travels out parallel.

Where do these rays meet? They don't. At least, not on the right side of the lens. To find your image, you have to use dotted lines to trace them backward to the left side. Where those dotted lines intersect? That’s your tiny, upright, virtual image.

Real-World Applications You Actually Use

We aren't just drawing these for fun or to pass 10th-grade science. This math keeps society moving.

Myopia (Nearsightedness)

If you're nearsighted, your eye is a bit too long or your cornea is too curved. Light focuses in front of your retina instead of on it. Everything is a blur. An optometrist uses the principles of a concave lens ray diagram to prescribe a lens that spreads the light out just enough so that by the time it hits your eye, it finally lands on the retina correctly.

Laser Tools

Ever see a laser level at a construction site? Or a high-powered medical laser? Sometimes the beam is too narrow. Engineers use concave lenses to expand the beam. By understanding the exact angle of divergence, they can predict how wide that beam will be ten meters down the line.

💡 You might also like: Pink iPad 10th Generation 256GB: What Most People Get Wrong

The Flashlight Trick

Flashlights and car headlights often use a combination of mirrors and lenses. If you want a wide, soft beam instead of a piercing spotlight, a concave element helps "throw" the light across a wider area.

The Math Behind the Lines

If you want to get technical—and since you're reading an expert guide, I assume you do—we use the Lens Formula. It looks like this:

$$\frac{1}{f} = \frac{1}{v} - \frac{1}{u}$$

In this equation, $f$ is the focal length. For a concave lens, $f$ is always negative. That’s a rule you can't break. $v$ is the distance of the image from the lens, and $u$ is the distance of the object.

When you crunch these numbers, you’ll notice that $v$ always comes out negative too. That’s the math’s way of saying "Hey, the image is on the same side of the lens as the object!" This confirms everything we saw in our concave lens ray diagram.

Common Mistakes to Avoid

Most students and hobbyists trip up on the same few things. Don't be that person.

First, people forget the arrows. Light has a direction. If your diagram doesn't have arrows showing which way the light is traveling, it’s just a bunch of meaningless lines.

Second, the "dotted line" rule. Real rays are solid lines. Virtual rays (the ones you trace backward) must be dotted. This distinguishes between where the light actually is and where your brain thinks it’s coming from.

Third, the focal point placement. A lens has two focal points, one on each side. In a concave lens ray diagram, you are primarily using the one on the same side as the object to determine the angle of divergence.

Why Does It Always Look Smaller?

It feels counterintuitive. Why can't we get a big image from a concave lens?

It's about the "spread." Because the rays are always moving away from the principal axis, the point where they seem to converge (the virtual image) is forced to be closer to the axis than the original object height. There is no physical way to position an object near a single concave lens and get a magnified image. It’s mathematically impossible.

This is why, if you want to zoom in on something like a bird in a tree, you need a complex system of multiple lenses (like a telescope or a telephoto camera lens). Those systems use concave lenses to correct distortions caused by the big convex ones, but they never work alone if magnification is the goal.

Nuance: The Thickness Factor

Not all concave lenses are the same. A "deep" curve (a high-power lens) will diverge light much more aggressively than a shallow one.

In a concave lens ray diagram, a shorter focal length means the focal point is closer to the lens. This results in a much sharper angle of divergence. If you’re designing a pair of glasses for someone with severe myopia, those lenses are going to be thick at the edges and very thin in the middle to create that aggressive bend.

✨ Don't miss: 106 Celsius to Fahrenheit: Why This Temperature Is More Than Just a High Number

Actionable Steps for Mastering Optics

If you're trying to nail this for a project or an exam, stop just looking at pictures. You have to draw them.

- Get Graph Paper: It makes keeping your parallel lines actually parallel much easier.

- Use Three Colors: Use one color for the parallel ray, one for the center ray, and one for the focal ray. It makes the intersection point much more obvious.

- Measure Your Focal Length: Don't just guess where 'F' goes. If you place it at 5cm, make sure the one on the other side is also exactly 5cm.

- Test Different Distances: Draw one diagram with the object far away (beyond 2F) and one with the object very close (between F and the lens). You'll see that while the image stays virtual and small, its exact size and position shift slightly.

Understanding the concave lens ray diagram is basically like having a cheat code for how light behaves. It removes the mystery of why your glasses work or why your security camera sees so much of your porch. It’s all just light trying to take the fastest path, getting bent by a piece of curved glass along the way.

Next Steps for Deep Learning

- Analyze Your Own Gear: Take a look at a pair of "minus" power glasses (nearsighted). Move them away from a piece of text and watch how the words shrink.

- Simulation Practice: Use an online optics simulator (like PhET) to drag an object back and forth in front of a virtual concave lens. Watch the rays react in real-time to reinforce the "backward tracing" concept.

- Combine Lenses: Once you're comfortable with the single lens, try drawing a two-lens system. Use the image from the first lens as the object for the second. This is how real-world camera lenses are designed.