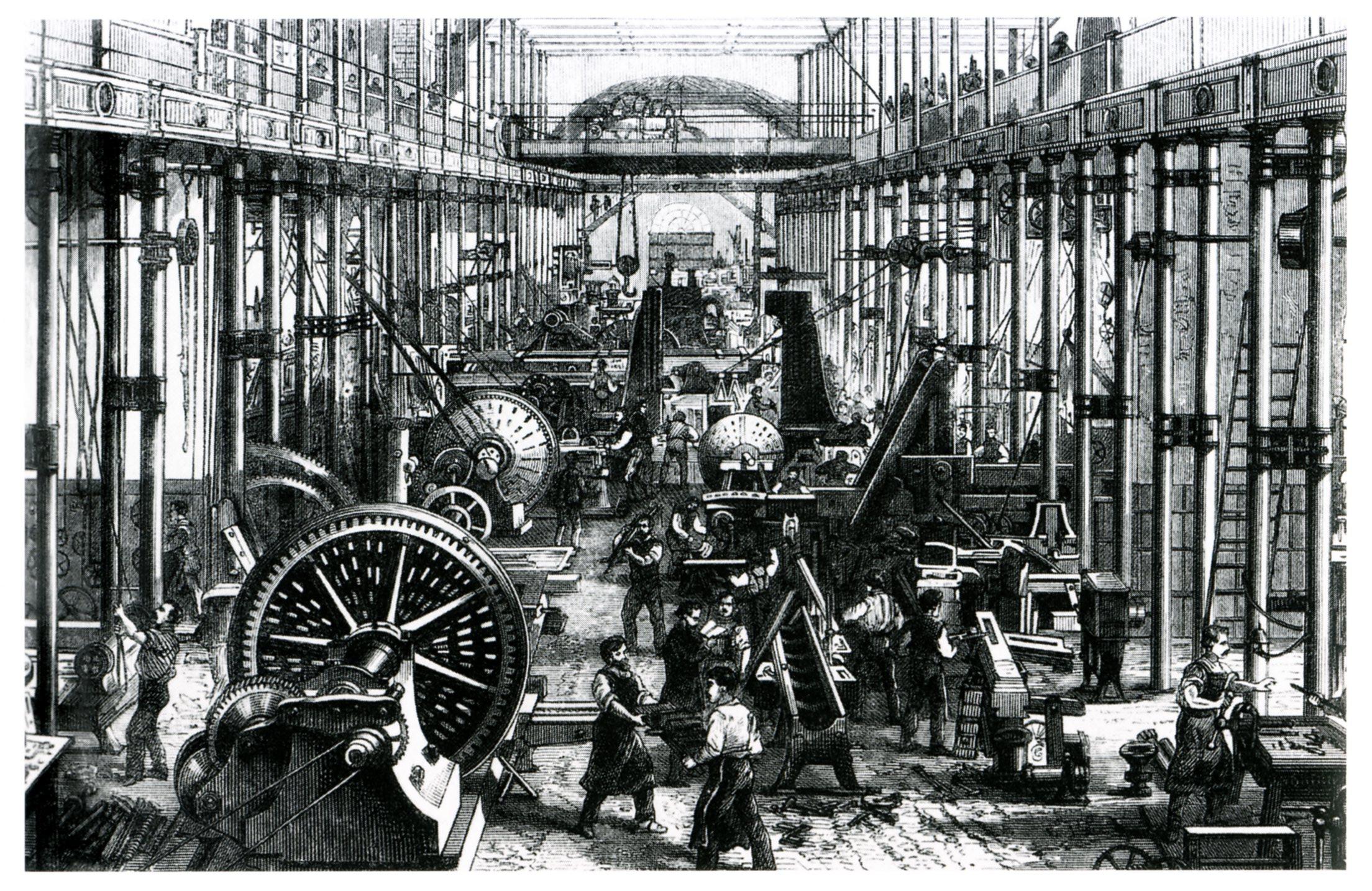

When you look at pics of industrial revolution era factories or smog-choked streets, it’s easy to feel a sense of detachment. The grainy, sepia-toned quality makes everything seem like a different planet. But honestly? Those photos are more relatable than we think. They aren't just snapshots of old machines; they are the visual receipts of the biggest pivot in human history.

If you’ve ever scrolled through the archives of the Library of Congress or the National Archives, you’ve probably seen the "Breaker Boys"—small kids covered in coal dust, staring into the camera with eyes that look fifty years older than they are. Lewis Hine, the guy who took many of those famous shots, wasn't just a photographer. He was basically a private investigator for social justice. He’d sneak into mills and factories, often under a pseudonym, just to document the reality that the owners wanted to keep hidden.

The Problem With "Staged" History

One thing people often miss is that early photography was a massive ordeal. You couldn't just whip out a smartphone. Because of long exposure times, the pics of industrial revolution life we see are frequently "staged" out of necessity. People had to stand perfectly still. This is why everyone looks so miserable. It wasn’t just the grueling 14-hour shifts (though that was part of it); it was the fact that moving an inch would blur the entire frame into a ghostly mess.

Take the famous daguerreotypes of mid-1800s locomotives. They look pristine, almost like toys. That’s because the photographers chose moments when the steam was settled and the workers were positioned like statues. It gives us a skewed view of the era as being quiet and orderly. In reality, these places were deafening. The clatter of power looms in a textile mill could be heard from blocks away, and the vibration was enough to rattle teeth. We see the image, but we lose the sensory violence of the actual scene.

📖 Related: Dyson V15s Detect Submarine Absolute: Is a Mop-Vacuum Hybrid Actually Worth the Money?

Why These Industrial Revolution Pics Still Matter Today

We live in a world of high-speed internet and AI, but we’re still riding the rails laid down in the 1800s. Literally. Many of the bridges and tunnels captured in 19th-century photography are still in use. When you see a photo of the construction of the Forth Bridge in Scotland (1880s), you’re looking at the birth of modern structural engineering.

The transition from "hand-made" to "machine-made" wasn't just a business shift. It changed how humans perceived time. Before the factory system, you worked by the sun. Afterward? You worked by the clock. You can see this in the architecture of the factories themselves. The massive windows weren't for a "boho aesthetic"—they were the only way to get enough light to work before Edison’s lightbulb became mainstream.

The Environmental Toll in Black and White

There's a specific type of photo from this era that always hits hard. It's the landscape shot. If you look at 1870s pics of industrial revolution hubs like Sheffield or Pittsburgh, the sky is just... gone. It’s a solid wall of gray.

Experts like Dr. Stephen Mosley, who writes about the history of environmental pollution, point out that smoke was actually seen as a sign of "progress" for a long time. If there was smoke, there were jobs. It’s a wild mindset to wrap your head around today. These photos document the exact moment we started trading air quality for economic output. In some shots of the River Thames from the late 1800s, the water looks like mercury. It basically was a toxic soup.

What the History Books Skip

Most people think of the Industrial Revolution as a British thing. It started there, sure. James Watt and his steam engine get all the credit. But the visual record shows a global upheaval. Photos from the Meiji Restoration in Japan show a society jumping 200 years forward in about two decades. You’ll see a man in a traditional kimono standing next to a modern telegraph pole. It’s a jarring contrast.

🔗 Read more: Why Mars Curiosity Rover Pictures Keep Messing With Our Heads

Then there’s the role of women. We often see photos of "Mill Girls" in Lowell, Massachusetts. These women were some of the first to gain a level of financial independence, even if the conditions were cramped and the "boarding houses" were strictly monitored. Their faces in these photographs tell a complex story—one of exhaustion, but also of a new kind of social identity. They weren't just farm daughters anymore; they were a workforce.

Technical Reality: How These Images Were Captured

Early cameras used glass plates. They were heavy. They were fragile. A photographer heading out to capture the building of the Transcontinental Railroad had to lug hundreds of pounds of equipment across mountains.

- The Wet Plate Process: This required the photographer to coat, expose, and develop the plate in about ten minutes. If the chemicals dried, the photo was ruined. This is why so many pics of industrial revolution sites are taken from a distance; the photographer had to set up a portable darkroom tent nearby.

- The Impact of Flash: Early "flash" was basically gunpowder (magnesium powder). It was dangerous and smoky. This is why indoor photos of mines or tenements are so rare before the 1890s. When Jacob Riis started using flash to document New York slums, he literally set fire to buildings on more than one occasion.

- The Perspective: Most industrial photos were commissioned by the companies. They wanted to show off their wealth. That’s why you see so many shots of massive, empty engine rooms. They wanted to highlight the machine, not the person.

Misconceptions About the "Good Old Days"

There is a weird nostalgia some people have for this era. They see the brickwork and the iron and think it was "classy."

It wasn't.

The photos don't show the smell. They don't show the fact that "The Great Stink" in London was so bad in 1858 that they had to soak the curtains of Parliament in lime to keep the politicians from fainting. When you look at pics of industrial revolution housing, notice the lack of plumbing. Look at the gutters. Those photos are a record of a public health crisis that eventually forced the creation of modern city planning and sanitation.

The Evolution of the "Work" Photo

As the 19th century turned into the 20th, the style of these images changed. We moved from "look at this big machine" to "look at what this machine is doing to people." This shift is crucial. It’s the birth of documentary photography.

Photographers like August Sander began to categorize people by their jobs. The "Worker" became a visual archetype. You can see the grime etched into the skin in his portraits. This wasn't just art; it was a socio-economic map. It’s a reminder that the "working class" as a concept was essentially invented during this period, and the camera was there to catch its first breath.

How to Analyze Industrial Era Photos for Authenticity

If you’re looking at an old photo and trying to figure out if it’s actually from the peak Industrial Revolution (roughly 1760–1840) or the later Victorian industrial boom, look at the details.

- Clothing: Are the men wearing top hats or flat caps? Top hats were more common for "overseers" in the mid-century, while the flat cap became the uniform of the everyman later on.

- Light Sources: If you see electric bulbs, you’re looking at post-1880. If the factory is lit by massive skylights and nothing else, it’s earlier.

- The Machinery: Early machines used leather belts connected to a central ceiling shaft. This was incredibly dangerous. If a belt snapped, it could decapitate someone. Later photos show "individual" motors on machines, which was a massive safety upgrade.

- The Background: Look for "smog." In the early days of the revolution, the industry was often rural, located near fast-moving rivers for water power. If the photo shows a dense forest of chimneys, it’s the high-urbanization period of the late 1800s.

The Human Element

I think the most haunting pics of industrial revolution history are the ones where someone accidentally moved. You see a sharp image of a massive steam hammer, but the person operating it is just a blur—a ghost in the machine. It’s a perfect metaphor for how the era treated individuals. They were replaceable parts in a massive, churning engine of capital.

The "Luddites" get a bad rap today as being anti-technology. But if you look at the photos of the world they were living in, you kind of get it. They weren't afraid of the machines; they were afraid of what the machines would do to their communities and their autonomy. The photos of that era's rapid urban sprawl show exactly what they feared: the destruction of the "cottage industry" where people worked in their own homes.

Modern Takeaways: What Can We Actually Do With This Information?

Looking at these images shouldn't just be a history lesson. It’s a mirror. We are currently in the middle of a "Fourth Industrial Revolution" (AI, biotech, etc.). The anxieties we see in the eyes of those 19th-century workers are the same anxieties people have today about automation.

👉 See also: Roscosmos: What Most People Get Wrong About the Future of Russian Space

If you want to dive deeper into this, don't just look at Google Images. Go to the digital collections of the British Museum or the Getty. Look for the "unposed" shots.

Actionable Steps for History Enthusiasts

- Visit a "Living Museum": Places like Ironbridge Gorge in the UK or Lowell National Historical Park in the US allow you to see these machines in motion. Seeing a power loom in person makes those static pics of industrial revolution life make way more sense. The noise is something you have to feel in your chest.

- Check Local Archives: Most industrial cities (Manchester, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Essen) have local libraries with massive photo collections that haven't been fully digitized. You can often find photos of your own neighborhood from 150 years ago.

- Research the "Social Gospel" Movement: If you want to understand the why behind many photos, look into the reformers who commissioned them. Photography was the "social media" of 1890, used to viralize the need for child labor laws.

- Study Photogrammetry: For the tech-savvy, many industrial artifacts are being 3D scanned. You can actually "walk through" digital recreations of old mills based on these historical photos.

The Industrial Revolution wasn't just a period of time; it was the moment we decided to trade the natural world for a built one. The photos we have are the only honest witnesses left to that trade. They show the triumph of engineering, sure, but they also show the scars it left behind. Next time you see one of these old pictures, look past the big iron machines. Look at the floor. Look at the windows. Look at the soot on the walls. That’s where the real story is.

To get the most out of your research, prioritize sources that provide high-resolution "un-cropped" versions of these images. Often, the most telling details—like the age of the helpers in the background or the condition of the workers' shoes—are hidden at the edges of the frame. Understanding these visual cues changes the way you see the modern world, especially when you realize how much of our current infrastructure is just a layer of paint over 19th-century bones.