Space is big. Really big. You’ve probably heard that before, but you don't actually feel it until you look at the Voyager 1 pictures of Earth taken from the freezing outskirts of our solar system. On February 14, 1990, a robotic explorer turned its camera back toward home one last time. It was roughly 3.7 billion miles away. At that distance, our entire world—every war, every wedding, every person you've ever loved—was reduced to a single, lonely pixel.

It almost didn't happen.

NASA didn't originally plan to take those photos. The mission was about Jupiter and Saturn. Once those were done, Voyager 1 was technically "finished" with its primary objectives. Carl Sagan, the legendary astronomer, had to beg NASA leadership to turn the cameras around. He knew it wouldn't have much scientific value, honestly. It was a sentimental gesture. Some engineers were actually worried that pointing the camera so close to the Sun might fry the sensitive vidicon detectors. Thankfully, they took the risk.

The Day Voyager 1 Pictures of Earth Changed Everything

The most famous of the Voyager 1 pictures of Earth is, of course, the Pale Blue Dot. If you look at the raw image, it’s actually quite messy. There are these weird streaks of light cutting across the frame. Those aren't cosmic rays or alien signals; they're just sunlight scattering off the camera's sunshade. Because the spacecraft was so far away, the Sun was still incredibly bright, even if it looked like a tiny, brilliant pinprick. Earth is caught in one of those beams, looking like a dust mote suspended in a sunbeam.

It’s sobering.

We tend to think of our world as this massive, indestructible thing. But when you see it from the perspective of Voyager 1, you realize how fragile the whole setup is. There’s no "planet B" visible in the frame. There’s no help coming from elsewhere to save us from ourselves. It's just us, floating in a vast, cold theater of nothingness.

The Technical Nightmare of Getting the Shot

Taking photos from 6 billion kilometers away isn't like snapping a selfie on your iPhone. Voyager 1 uses technology from the early 1970s. We're talking about 8-track tape recorders and computers with less memory than a modern key fob.

📖 Related: How to actually make Genius Bar appointment sessions happen without the headache

To get the "Family Portrait" series—which included Earth, Venus, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune—the spacecraft had to take 60 different frames. It took months for all that data to trickle back to Earth. Each pixel had to be transmitted as a series of radio pulses across the void, traveling at the speed of light but still taking over five hours to reach NASA’s Deep Space Network antennas.

- The imaging team had to calculate the exact orientation of the craft to ensure Earth would even be in the frame.

- They had to account for the "smear" caused by the spacecraft's motion.

- The "Pale Blue Dot" was captured using a narrow-angle lens with blue, green, and violet filters.

The results were grainy. They were noisy. But they were real.

Why We Can't Take New Voyager 1 Pictures of Earth

People often ask why we don't just ask Voyager 1 to take a "2026 update" photo. It’s a fair question. The short answer is: the cameras are dead. Not broken, exactly, but powered down.

Shortly after the 1990 photo session, NASA sent the command to turn off the cameras permanently. Voyager 1 is running on a decaying lump of plutonium (a Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator). Every year, it loses about 4 watts of power. To keep the heaters running and the transmitter talking to Earth, NASA has to make tough choices. The cameras were an easy sacrifice because, at this point, the spacecraft is in interstellar space. It’s so dark out there that there’s basically nothing for a visual light camera to see anyway.

It’s currently screaming through the void at about 38,000 miles per hour. Even at that speed, it won't pass near another star for another 40,000 years.

The Difference Between Voyager and Blue Marble

You've seen the "Blue Marble" photo from Apollo 17. That one is beautiful. It’s vibrant, showing the swirling clouds over Africa and the deep blues of the Atlantic. It makes Earth look like a lush, living jewel.

👉 See also: IG Story No Account: How to View Instagram Stories Privately Without Logging In

The Voyager 1 pictures of Earth do the opposite. They don't show life; they show the absence of everything else. While the Apollo photos make us feel big and important, the Voyager photos make us feel infinitely small. It’s the difference between looking at your house from the sidewalk versus looking at your city from a satellite. One is about home; the other is about context.

The Legacy of a Single Pixel

Carl Sagan’s reflection on this image remains the gold standard for scientific prose. He pointed out that every "hero and coward," every "creator and destroyer of civilization" lived right there on that tiny speck. It’s a powerful argument for environmentalism and, more importantly, for just being kind to one another.

When you look at the Earth from Voyager’s perspective, you can’t see borders. You can’t see religions. You can’t see different political ideologies. You just see a tiny, fragile life-support system.

It’s a perspective we desperately need right now.

Deep Space Network Challenges

Keeping in touch with the source of these images is getting harder. As of early 2026, Voyager 1 is over 15 billion miles away. The signals are getting weaker. Recently, the spacecraft had a major glitch with its Flight Data System (FDS), which sent back garbled binary code for months.

Engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) had to dig through decades-old manuals to fix it. Imagine trying to repair a computer from 1977 that is currently 22 light-hours away. They eventually figured out that a single chip had failed, and they managed to relocate the code to a different part of the memory. It worked. Voyager is talking again. But it’s a reminder that our link to the craft that gave us these images is fraying.

✨ Don't miss: How Big is 70 Inches? What Most People Get Wrong Before Buying

How to View the Original Voyager 1 Pictures of Earth

If you want to see the "real" photos, don't just look at the high-contrast, cleaned-up versions you see on posters. Go to the NASA Planetary Data System archives. The raw images are haunting. They are filled with "salt and pepper" noise and artifacts of the era's technology.

- The Family Portrait: This is a mosaic of 60 frames. It’s the only time a spacecraft has attempted to photograph our solar system from the "outside" looking in.

- The Narrow-Angle Earth: This is the specific "Pale Blue Dot" frame. Earth is roughly 0.12 pixels in size.

- The Solar System Wide-Angle: These shots show the Sun as a brilliant star, far brighter than any others in the sky, but no longer a "disk" with a visible surface.

What's Next for the Voyager Legacy?

While Voyager 1 will never take another photo, its mission continues as a silent ambassador. It carries the Golden Record—a copper phonograph record containing sounds of Earth, greetings in 55 languages, and music ranging from Bach to Chuck Berry.

The pictures it took served their purpose. They moved the needle on how we perceive our place in the universe. We moved from the "center of everything" to a "lonely speck in the great enveloping cosmic dark."

To truly appreciate the Voyager 1 pictures of Earth, you have to sit with them for a minute. Stop scrolling. Look at that tiny dot. Realize that everything you have ever known is contained within that microscopic point of light. It’s the most important mirror humanity has ever looked into.

Actionable Steps for Space Enthusiasts

If this bit of space history fascinates you, there are a few things you can do to dive deeper into the reality of interstellar exploration:

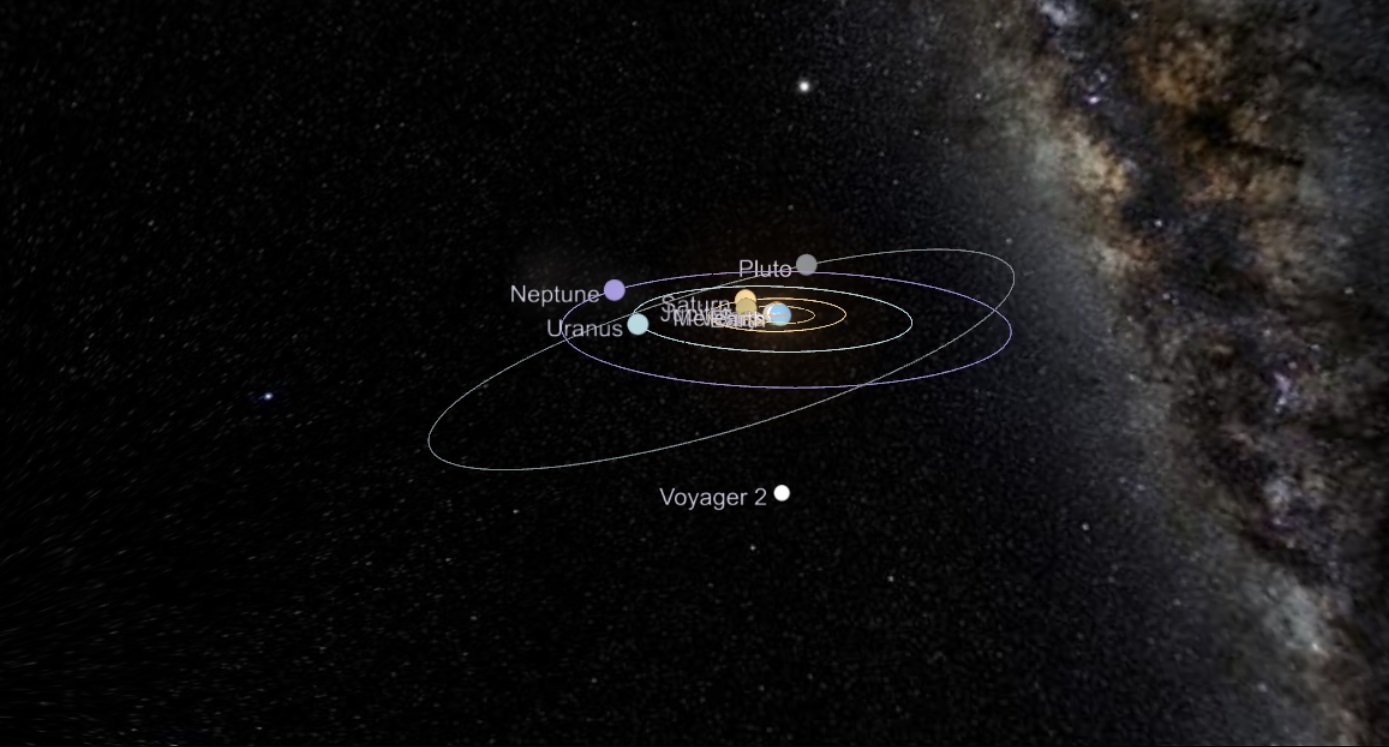

- Track Voyager in Real-Time: Use the NASA "Eyes on the Solar System" web tool. It shows you the real-time distance, speed, and status of both Voyager 1 and Voyager 2. You can see exactly how far they’ve traveled since you started reading this article.

- Study the Image Processing: Look up the work of Kevin M. Gill or other amateur image processors who take raw NASA data and turn it into the stunning visuals we see today. Understanding how a "grey" raw file becomes a "blue" dot helps you appreciate the science behind the art.

- Read the Source Material: Pick up Carl Sagan's book Pale Blue Dot. It’s not just about the photo; it’s a philosophy for the future of the human race in space.

- Visit the Smithsonian: If you're ever in D.C., the National Air and Space Museum has incredible exhibits on the Voyager missions, including full-scale replicas that show just how massive those radio dishes are.

The Voyager mission won't last forever. In a few years, the power will drop too low to run any instruments at all. Voyager 1 will become a silent ghost ship, drifting through the Milky Way for millions of years. But the images it sent back—especially that tiny, pale blue pixel—will remain some of the most important data points in human history. They told us where we are, but more importantly, they showed us how much we have to lose.