Think about a orange. If you peel it, you’ve got these weird, curved shards of skin that never quite lay flat on the table no matter how hard you press. This is the fundamental headache of non-Euclidean geometry. You can't just "unroll" a sphere like you can a cylinder or a cone. Because of that, the sphere surface area formula feels a bit like a magic trick when you first see it in a textbook. It’s $A = 4\pi r^2$.

Why four? Why exactly four circles?

It’s one of those things we memorize for a test and then immediately flush out of our brains. But honestly, if you're looking at satellite coverage, designing a sleek new PC case, or even just wondering how much leather goes into a regulation FIFA football, that little "4" is the most important number in your world. It’s a perfect mathematical symmetry that Archimedes—the absolute legend of Syracuse—found so beautiful he wanted it carved onto his tombstone.

Archimedes and the most beautiful proof in history

Archimedes didn't have calculus. He didn't have a high-powered computer or a 3D modeling suite. What he had was a massive brain and some sand to draw in. He discovered that the surface area of a sphere is exactly the same as the lateral surface area of a cylinder that "hugs" it perfectly.

Imagine a ball sitting inside a Pringles can. If the ball fits perfectly, touching the top, the bottom, and the sides, its surface area is identical to the area of the can's walls.

This is mind-blowing. If you take that cylinder and flatten it out, it's just a rectangle. The height of that rectangle is the diameter of the sphere ($2r$), and the width is the circumference of the sphere ($2\pi r$). Multiply them together? You get $4\pi r^2$. It’s elegant. It’s clean. It makes you realize that math isn't just a bunch of arbitrary rules; it's a description of how the universe actually fits together.

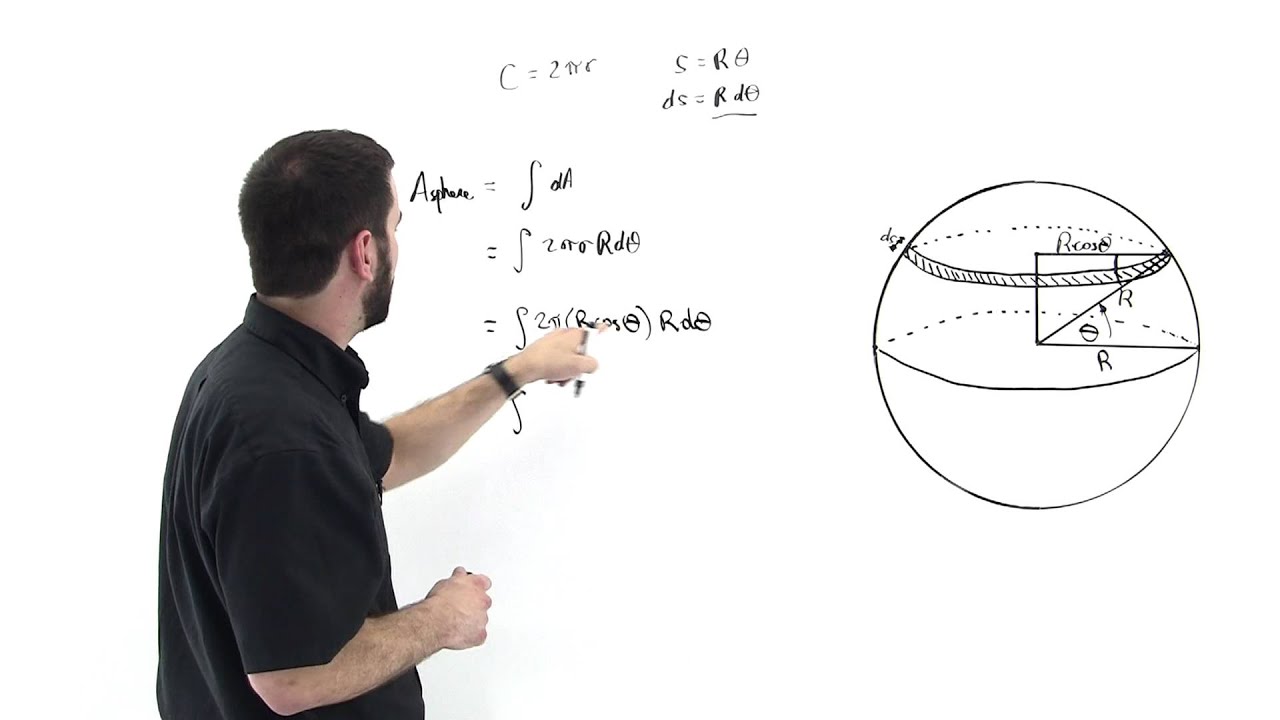

The math behind the sphere surface area formula

Let's look at the actual variables. You’ve got $r$, which is the radius. That’s the distance from the very center of the ball to any point on the shell. Then you’ve got $\pi$, which is roughly $3.14159$, though if you’re doing high-precision engineering, you’re using way more decimals than that.

The formula is:

$$A = 4\pi r^2$$

If you’re working with the diameter ($d$) instead of the radius—maybe you’re measuring a physical object with calipers—you can swap it out. Since $r = \frac{d}{2}$, the formula becomes $A = \pi d^2$.

Some people get confused and try to use the volume formula ($V = \frac{4}{3}\pi r^3$) when they should be using surface area. Easy mistake. But think about the units. Area is always squared (like square inches or square meters). Volume is always cubed. If your answer isn't in square units, you’ve grabbed the wrong tool from the shed.

Why does the "4" matter so much?

If you took a sphere and projected it onto a flat map—like we do with the Earth—you realize you can't do it without stretching something. This is the Mercator projection problem. The sphere surface area formula tells us the absolute truth of the size, but a flat map lies to you. Greenland looks huge on a map, but the formula doesn't lie. It tells us exactly how much "skin" is there.

🔗 Read more: Tesla Model X Doors Explained: What Owners (And Critics) Always Get Wrong

Actually, think of it this way: the surface area of a sphere is exactly four times the area of its own cross-section. If you cut a baseball right down the middle, the area of that flat circle is $\pi r^2$. It takes exactly four of those circles to cover the entire outside of the ball. No more, no less. It’s a weirdly perfect ratio that seems too simple to be true, yet it holds up whether you're measuring a marble or a star.

Real-world chaos: When the formula gets messy

In the real world, nothing is a perfect sphere. The Earth isn't. It’s an oblate spheroid. It’s got a bit of a "spare tire" around the equator because it’s spinning so fast. If you use the standard $4\pi r^2$ for the Earth, you’re going to be off by a few hundred square kilometers.

For most of us, that doesn't matter. But if you’re NASA? It matters a lot.

Then you have things like "specific surface area" in chemistry. If you take a solid sphere and crush it into a powder, the surface area explodes. This is why dust can be explosive—massive surface area means massive reactivity. Engineers use the sphere as a baseline because it has the smallest surface area for any given volume. It’s the most efficient shape in nature. That’s why raindrops are spherical and why bubbles form the way they do. Nature is cheap; it wants to use the least amount of energy (and material) possible.

How to calculate it without losing your mind

If you're staring at a problem right now, just follow the steps. It’s basically a recipe.

- Find the radius. If you only have the distance across (diameter), cut it in half.

- Square it. Multiply the radius by itself. This is where most people trip up—they multiply by two instead of squaring. Don't do that.

- Multiply by 4. 4. Multiply by $\pi$. Use $3.14$ for a quick estimate, or the $\pi$ button on your calculator for the real deal.

Let's say you have a basketball with a radius of $4.7$ inches.

$4.7$ squared is $22.09$.

Multiply that by $4$ and you get $88.36$.

Multiply that by $\pi$ and you're looking at roughly $277.6$ square inches of leather.

Beyond the classroom: Why this matters for the future

We’re starting to look at things like Dyson spheres (theoretical megastructures around stars) and advanced cell-based medicine. In both cases, the ratio of surface area to volume is the "limiting factor."

In biology, a cell can only get so big before its surface area (the "doorway" for nutrients) is too small to support its volume (the "room" that needs food). This is why you don't see giant, single-celled amoebas walking down the street. The sphere surface area formula is literally a law of physics that dictates how large life can grow and how heat escapes from a planet.

Actionable steps for mastering the geometry

If you want to actually get good at this, stop just staring at the numbers.

- Visualize the 4 circles: Whenever you see a sphere, imagine four circles of the same width wrapped around it. It helps the "4" stick in your head.

- Check your units: Always write down "units squared" at the end. If you're calculating the area of a planet in kilometers, your answer is in $km^2$.

- Use the right tools: For quick dirty math, use $d^2 \times 3.14$. For anything involving money, safety, or grades, use the full radius-based formula.

- Practice with real objects: Measure a grapefruit. Calculate its surface area. Then peel it and try to fit the peel into four circles you've drawn on a piece of paper. Seeing it work in real life makes the math "click" in a way a screen never can.

The math isn't just a hurdle to get over. It's the language used to describe everything from the bubbles in your soda to the curve of the horizon. Once you see the "4" in the sphere, you start seeing the geometry of the world everywhere.