You're driving down a highway. You glance at the dashboard. The needle sits right on 65. Most people call that their speed, and they’re technically right, but physics is a bit more pedantic about it. In the world of classical mechanics, the definition of speed in physics is strictly the rate at which an object covers distance. It doesn't care if you're going North, South, or driving in a giant circle until you're dizzy. It’s a scalar quantity. That sounds fancy, but it basically just means it’s a number with a unit attached. No direction. No fluff. Just how fast you’re moving.

Speed is one of those foundational concepts that seems easy until you start looking at the math. Then it gets weird. Or at least, more specific. Think about the difference between a snapshot and the whole trip. If you drive to your grandma's house 100 miles away and it takes you two hours, your average speed was 50 mph. But were you going 50 the whole time? Probably not. You hit red lights. You sped up to pass a slow truck. You stopped for a coffee. That distinction—the "average" versus the "instant"—is where most students and curious minds get tripped up.

How Physics Actually Defines Speed

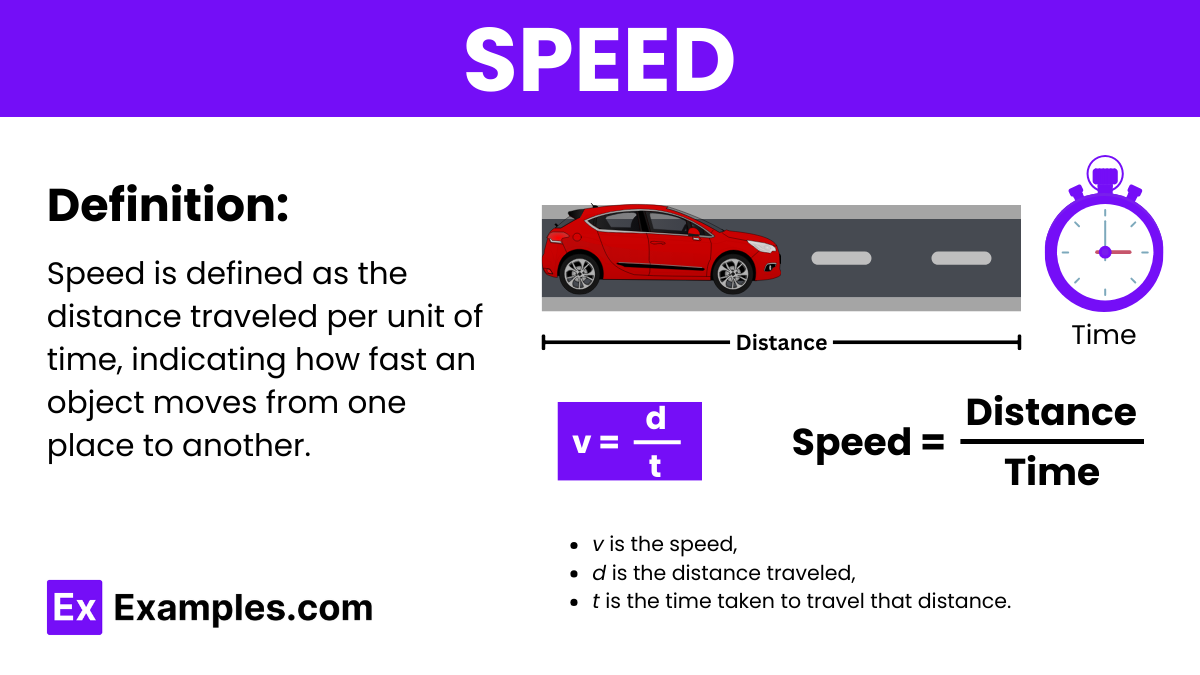

In a formal setting, like a lab at MIT or a high school classroom, we define speed as the distance traveled divided by the time it took to get there. It’s the "how much" of motion. If you want to get technical, the formula is:

$$v = \frac{d}{t}$$

Here, $v$ is the speed (derived from the Latin velocitas, though we use it for speed too), $d$ is distance, and $t$ is time.

The SI unit—the gold standard for scientists—is meters per second (m/s). Sure, we use miles per hour in the States or kilometers per hour in Europe, but if you’re calculating the rate of a tectonic plate shifting or a photon zipping through a vacuum, you're sticking to meters and seconds.

Why Direction Changes Everything

People often use "speed" and "velocity" like they're the same thing. They aren't. Not even close in the eyes of a physicist. Imagine you're running on a circular track. If you run one lap in 60 seconds, your speed is whatever the distance of the track is divided by 60. But your velocity? If you end up right back where you started, your average velocity is actually zero.

📖 Related: What Was Invented By Benjamin Franklin: The Truth About His Weirdest Gadgets

Wait. Zero?

Yeah. Because velocity is a vector. It tracks displacement—the straight-line distance between start and finish. Since you started and stopped at the same point, you didn't technically "displace" yourself at all. Speed, however, is honest. It counts every grueling step you took on that track. This is why the definition of speed in physics is so vital; it measures the actual effort of movement regardless of the final destination.

The Two Faces of Speed: Instantaneous vs. Average

Most of us live in the world of averages. If you tell a friend you "ran at a speed of 6 mph," you're giving them an average. You didn't instantly teleport to 6 mph the moment your foot hit the pavement.

Instantaneous speed is what that speedometer in your car shows. It’s the speed at a specific moment in time. If you could freeze time to a billionth of a second, how fast would you be going? In calculus, we represent this as the limit of the average speed as the time interval approaches zero. It sounds like a headache, but it’s just the math of "right now."

Average speed, on the other hand, is the big picture. It’s the total distance divided by the total time. It ignores the stops, the starts, and the frantic braking for a squirrel.

- Total Distance: 300 miles

- Total Time: 5 hours

- Average Speed: 60 mph

It’s a simple ratio. But it’s a ratio that governs everything from flight paths to how long it takes for a signal to travel from your brain to your fingertips.

👉 See also: When were iPhones invented and why the answer is actually complicated

Real-World Examples That Break the Brain

Let's talk about the fastest things we know. Light is the champion. In a vacuum, light travels at roughly 299,792,458 meters per second. That is the ultimate speed limit of the universe. According to Einstein's theory of special relativity, nothing with mass can ever reach that speed because it would require infinite energy.

Then you have things on the other end of the spectrum. Tectonic plates move at about the same speed your fingernails grow—roughly 1 to 10 centimeters per year. It's still a speed. It still follows the $d/t$ rule. It just takes a lot more patience to measure.

Consider a professional pitcher. A fastball might clock in at 100 mph. That's instantaneous speed as it leaves the hand. By the time it reaches the catcher’s mitt, air resistance (friction) has already slowed it down by a few miles per hour. This is why "exit velocity" and "pitch speed" are such huge stats in modern sports—they are measuring speed at incredibly precise moments to find a competitive edge.

The Problem with "Constant Speed"

In a textbook, things move at a constant speed all the time. In the real world? Almost never. Friction is a jerk. Air resistance is always pushing back. Even a puck on "frictionless" ice eventually slows down. To maintain a constant speed, you have to constantly apply force to counteract these invisible hands trying to stop you. This is why your car needs to burn gas even when you're just maintaining 70 mph on a flat road. You aren't paying to go faster; you're paying to not go slower.

Why Does This Definition Actually Matter?

You might wonder why we obsess over the definition of speed in physics so much. Isn't "how fast" enough? Not if you're building a world.

Engineers at NASA have to calculate the speed of a probe with terrifying precision. If they're off by a fraction of a percent, that billion-dollar piece of hardware misses Mars entirely and sails off into the dark. In medicine, the speed of blood flow through an artery can tell a doctor if a patient is at risk for a stroke. In gaming, physics engines have to calculate the speed of every digital object to make sure the "feel" of the game isn't floaty or weird.

✨ Don't miss: Why Everyone Is Talking About the Gun Switch 3D Print and Why It Matters Now

Common Misconceptions to Toss Out

- Speed can be negative. Nope. Never. Velocity can be negative because you can go in a "negative" direction (like backward), but speed is always positive or zero. You can't "un-travel" a distance.

- High speed kills. Actually, it's the acceleration (the change in speed) that gets you. Or rather, the sudden stop. Moving at 1,000 mph feels like nothing if it's constant. Just ask the people on the International Space Station—they're orbiting at 17,500 mph right now, and they're probably just eating rehydrated mac and cheese.

- Speed is the same as pace. In running, pace is time per distance (minutes per mile). Speed is distance per time. They're related, but they're flips of each other.

Technical Nuance: The Role of the Reference Frame

Here is where it gets kind of trippy. Speed depends on who is looking.

If you are sitting on a train moving at 50 mph and you walk toward the front of the train at 3 mph, how fast are you going? To the person sitting in the seat next to you, you're going 3 mph. To someone standing on the side of the tracks watching the train zoom by, you're going 53 mph.

This is the concept of a "reference frame." In physics, when we define speed, we usually have to implicitly agree on what we are measuring it against. Usually, that's the Earth. But since the Earth is spinning at 1,000 mph and orbiting the sun at 67,000 mph, we're all technically speeding right now, even if we're lying in bed.

Key Takeaways for the Curious

If you want to apply this knowledge, start by looking at your own life through a physics lens. Stop thinking about "how far" and start thinking about the rate.

- Audit your commute: Use your odometer and a stopwatch. Is your average speed significantly lower than the speed limits you see? That tells you how much time you're losing to intersections.

- Watch the "instant": Next time you use a GPS app, notice how the "current speed" lags slightly behind your actual car. That's because the app is calculating average speed over a very tiny slice of time (usually one second) based on satellite pings.

- Respect the vector: Remember that speed is just one half of the story. If you're planning a trip or analyzing a sport, always ask: "Does the direction matter here?" If it does, you're talking about velocity.

Understanding the definition of speed in physics isn't just about passing a test. It's about seeing the machinery of the universe. It’s the realization that everything—from the smallest atom to the largest galaxy—is in a constant state of covering distance over time.

To dig deeper, you might want to explore the relationship between speed and kinetic energy. The faster an object moves, the more energy it carries, but it doesn't scale linearly. If you double your speed, you actually quadruple your kinetic energy. That’s why a car crash at 60 mph is vastly more destructive than one at 30 mph. Physics isn't just numbers on a page; it’s the literal rules of survival in a moving world.

Check your own "average speed" on your next walk. Divide your total steps (converted to miles or meters) by the total minutes you walked. You might find that you're a lot faster—or slower—than you thought. It’s all about the data.