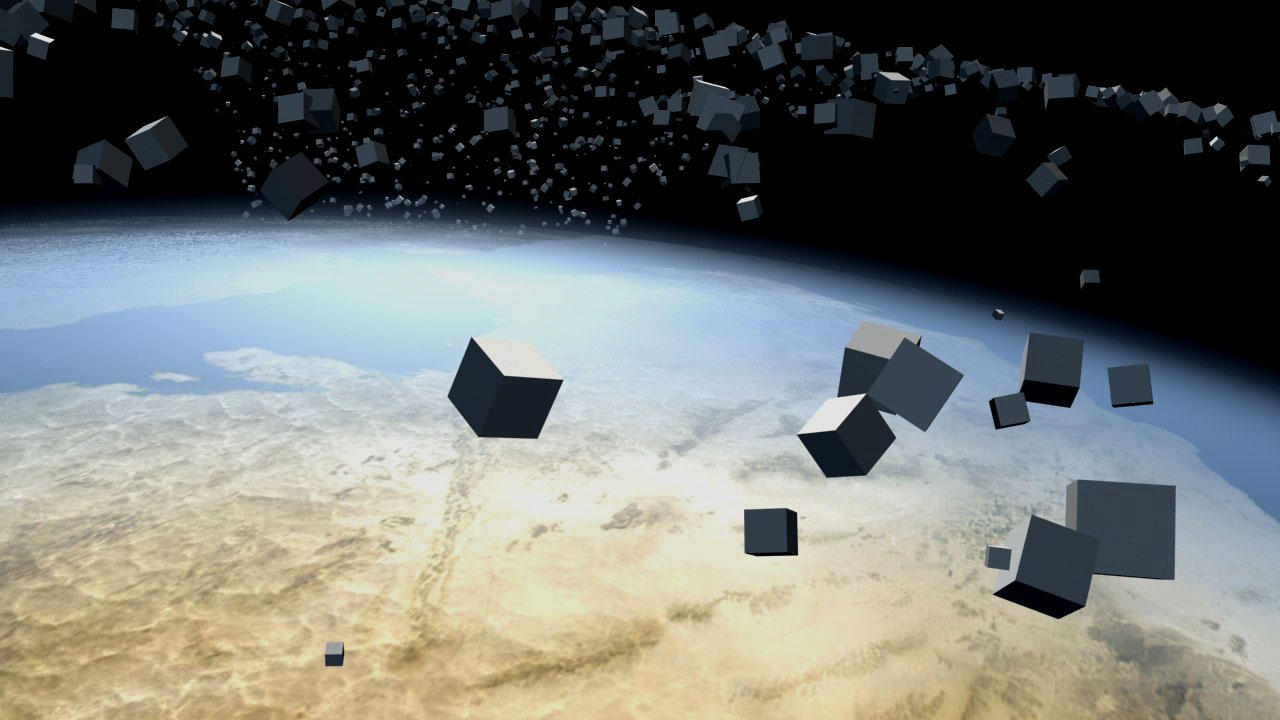

Look up. It looks empty, right? Just a vast, velvety void with a few twinkling stars and maybe the moon if it’s a clear night. But if you could actually see what was whipping around our planet at 17,500 miles per hour, you’d probably want to wear a helmet. Space is crowded. It’s dirty. Honestly, it’s kind of a junkyard.

When people ask how much trash is in space, they usually expect a number like "a few hundred old satellites." The reality is much more sobering. We are talking about millions of individual pieces of debris. Some of it is as big as a school bus. Most of it is smaller than a marble. All of it is dangerous.

The Numbers That Should Worry You

According to the European Space Agency (ESA) and NASA’s Orbital Debris Program Office, the stats are staggering. There are about 35,000 objects tracked by Space Surveillance Networks. These are the "big" ones—anything larger than 10 centimeters (about 4 inches). But the tracking stops there.

Estimates suggest there are roughly 1 million pieces of debris between 1 cm and 10 cm. If we go even smaller—down to the 1 millimeter range—we’re looking at over 130 million pieces.

Imagine a fleck of paint. Sounds harmless. Now imagine that fleck of paint hitting a space station window while traveling ten times faster than a bullet. That’s the physics of Low Earth Orbit (LEO). At those speeds, kinetic energy is a nightmare. A tiny metal fragment can pack the punch of a hand grenade.

What Exactly Is This Junk?

It’s not just banana peels and soda cans. Space junk is the graveyard of the Space Age. We’ve been launching things since Sputnik in 1957, and for decades, we didn't really have a "clean up" plan.

Most of the mass comes from spent rocket stages. These are the giant cylinders that fall away once a rocket reaches orbit. They just sit there, tumbling in the dark for decades. Then you have dead satellites. Batteries fail. Electronics fry. When a satellite dies, it doesn't just disappear; it stays in its orbital lane, a multi-million dollar ghost ship.

💡 You might also like: How to do a CMOS Reset Without Ruining Your Motherboard

Then it gets messy.

Fragments are the biggest problem. When two objects collide—or when an old rocket stage explodes because of leftover fuel—they create a "cloud" of shrapnel. In 2009, a defunct Russian satellite called Kosmos-2251 slammed into a functioning Iridium communications satellite. That single event created thousands of new pieces of trackable debris. It was a mess. A massive, orbital fender-bender that we’re still dealing with today.

The Kessler Syndrome: A Nightmare Scenario

Donald Kessler, a NASA scientist, proposed a theory in 1978 that keeps satellite operators up at night. It’s called the Kessler Syndrome.

Basically, it’s a domino effect.

The density of objects in LEO becomes so high that one collision creates debris, which then causes more collisions, creating even more debris. Eventually, the space around Earth becomes a self-sustaining storm of shrapnel. If this happens, certain orbital altitudes could become completely unusable. We could effectively trap ourselves on Earth, unable to launch new satellites or even send humans to the Moon because the "shell" of trash is too thick to pierce safely.

We aren't quite there yet. But we're getting closer. With the rise of "Mega-Constellations" like SpaceX’s Starlink, the sheer volume of hardware in the sky is exploding. There are thousands of new satellites being launched every year now. Even with "auto-maneuvering" tech, the margin for error is shrinking.

Why Can't We Just Vacuum It Up?

You’d think we could just send up a giant magnet or a net. People are trying!

✨ Don't miss: The Box by Alter: Why This $10,000 Speaker Is Actually Breaking the Laws of Physics

ClearSpace-1, a mission by the ESA, is aiming to grab a piece of debris using a "chaser" satellite with four robotic arms. It’s basically a cosmic claw machine. Other companies, like Astroscale, are testing magnets.

But here’s the rub: it’s incredibly expensive.

Launching a mission to remove one single piece of junk costs tens of millions of dollars. Who pays for it? The company that launched the satellite thirty years ago? Most of those companies don’t exist anymore. The government? Space is international waters. No one wants to foot the bill for someone else's trash.

Also, the physics is hard. Most debris is "non-cooperative." It’s tumbling wildly. If you try to grab a spinning rocket stage with a robot arm, you might just get slapped into a different orbit or break your own satellite, adding even more junk to the pile. It’s a delicate, high-stakes dance.

The Problem of "Ghost" Objects

There's a category of debris that people rarely talk about: solid rocket motor effluents. When some older rockets burned their fuel, they released tiny particles of aluminum oxide. These are microscopic, but there are trillions of them. They act like sandpaper, slowly eroding the surfaces of active satellites and telescopes.

Then there’s the "leaked coolant." In the 1980s, several Soviet RORSAT satellites leaked droplets of sodium-potassium coolant into space. Because of the cold, these droplets froze into solid metal spheres. Millions of tiny, frozen liquid-metal balls are currently orbiting Earth.

It sounds like science fiction. It’s just our reality.

Regulations and the Future

Thankfully, the "Wild West" era of space is slowly ending. Most space agencies now follow the "25-year rule." This means if you launch a satellite, you must have a plan to de-orbit it within 25 years of its mission ending.

How do they do it?

- Atmospheric Re-entry: Small satellites use their last bit of fuel to drop their altitude. They hit the atmosphere and burn up like shooting stars.

- Graveyard Orbits: For giant satellites high up in Geostationary Orbit (GEO), they don't have enough fuel to come back down. Instead, they kick themselves even further away into a "graveyard" lane where they won't bother anyone for a few thousand years.

But "rules" aren't laws. Not every country follows them. And even if everyone started following them tomorrow, we still have to deal with the sixty years of garbage already up there.

How Much Trash Is In Space Right Now? (The Summary)

To put a fine point on it, the total mass of human-made objects in Earth orbit exceeds 11,000 tonnes. That is the equivalent of about 800 school buses of pure metal, glass, and plastic circling us constantly.

While the "big stuff" like the International Space Station (ISS) has shields and can move to avoid tracked debris, the small stuff is a constant gamble. The ISS has had to perform "collision avoidance maneuvers" dozens of times over the years. Astronauts have even had to take shelter in their return capsules because a debris cloud was headed their way.

What Happens If We Do Nothing?

If we don't get serious about debris removal, the cost of everything will go up.

👉 See also: TikTok Profile Pic Downloader: How to Save High-Res Avatars Without the Headache

Your GPS might become less accurate. Your satellite TV might flicker out. Weather forecasting could become a guessing game. The "Space Economy"—which is worth hundreds of billions—relies on a clear path to orbit. If that path is blocked by 130 million pieces of trash, the modern world as we know it takes a massive hit.

Space isn't just for billionaires and scientists. It’s the backbone of our global infrastructure. It's time we started treating it like a resource worth protecting rather than a bottomless trash can.

Actionable Steps and Insights

Understanding the scale of orbital debris is the first step, but what can actually be done? The solution isn't just one "vacuum" mission; it’s a shift in how we operate in the vacuum.

- Support Space Sustainability Ratings: Just like we have "Leed" certifications for green buildings, organizations like the World Economic Forum are pushing for sustainability ratings for satellite operators. Supporting companies that prioritize clean orbits is a start.

- Pressure for International Policy: Unlike the oceans, space lacks a binding international treaty regarding debris cleanup. Policy advocacy for "Orbital Tolls"—where a portion of launch costs goes into a cleanup fund—is a growing movement in the aerospace community.

- Active Debris Removal (ADR) Investment: Watch companies like Astroscale and ClearSpace. Their success or failure over the next five years will determine if we can actually "reset" the clock on the Kessler Syndrome.

- Track the Progress: Use tools like "Stuff in Space" (a real-time 3D map) to visualize just how many objects are currently above you. It changes the perspective from an abstract problem to a tangible one.

The mess is significant, but it isn't irreversible yet. We just need to stop thinking of space as "away" and start thinking of it as our own backyard.