Space is big. Like, really big. Most of us grew up looking at classroom posters where the planets are lined up like a neat row of marbles, all roughly the same size, sitting just a few inches apart. It's a lie. Honestly, if those posters were drawn to scale, Earth would be a microscopic speck and you’d need a piece of paper miles long to reach Neptune. When we talk about the order of planets by size, we’re not just ranking numbers; we’re looking at the radical physical diversity of our solar system. Some of these worlds are bloated gas giants that could swallow Earth a thousand times over, while others are tiny, rocky husks barely larger than our own moon.

Size defines everything in space. It dictates whether a planet can hold onto an atmosphere, if it stays geologically alive, or if it’s just a cold, dead rock drifting through the vacuum. Understanding the hierarchy from the kingly Jupiter down to the scorched crumb that is Mercury helps us realize just how "just right" our own home happens to be.

The Heavy Hitters: The Gas and Ice Giants

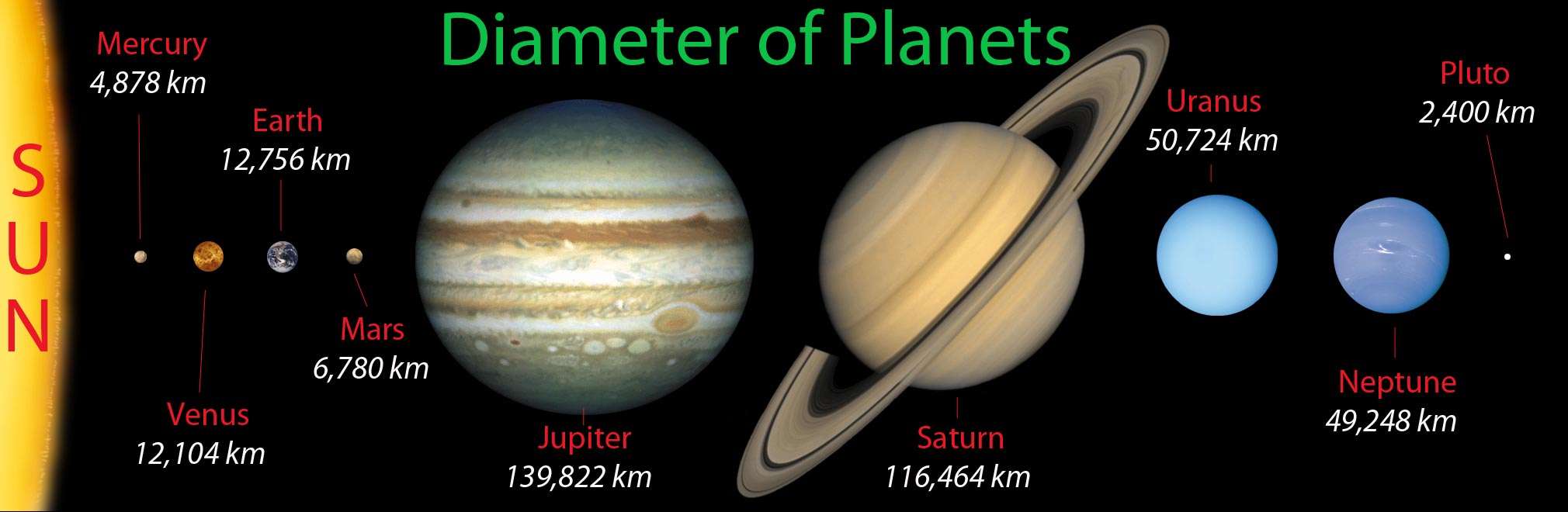

Jupiter is the undisputed heavyweight champion. It’s basically a failed star. If Jupiter had been about 80 times more massive, it might have started nuclear fusion itself. It’s so big that it doesn't actually orbit the center of the Sun; instead, both the Sun and Jupiter orbit a spot just above the Sun's surface called the barycenter. Its diameter is roughly 86,881 miles (139,820 km). That’s about 11 Earths lined up side-by-side. You could fit 1,300 Earths inside it. Think about that. Every mountain, ocean, and city we’ve ever known would just be a tiny drop in Jupiter’s Great Red Spot, a storm that has been raging for centuries.

✨ Don't miss: Why Apple Store at Tysons Still Matters 25 Years Later

Saturn follows close behind, though "close" is a relative term in the order of planets by size. It’s the second-largest, famous for those icy rings that make it look like a cosmic jewel. Saturn is about nine times wider than Earth. Interestingly, it’s also the least dense planet. If you had a bathtub big enough, Saturn would float. This is because it's mostly hydrogen and helium. While it looks massive, it lacks the crushing density of the inner planets.

Then we hit the "twins" that aren't actually twins: Uranus and Neptune.

Uranus takes the third spot. It’s an "ice giant," which is a fancy way of saying it has a lot more "ices" like water, ammonia, and methane than the gas giants. It’s about four times the diameter of Earth. One of the weirdest things about Uranus is that it rotates on its side. It’s basically rolling around the Sun. Why? Most astronomers, like those at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory, believe a massive collision early in its life knocked it over.

Neptune is technically fourth in size, but here’s the kicker: it’s actually more massive than Uranus. Even though Uranus is slightly wider (about 31,518 miles compared to Neptune’s 30,599 miles), Neptune is denser. It’s got more "stuff" packed into a slightly smaller ball. It’s a blue, wind-whipped world where the storms move faster than the speed of sound.

The Inner Circle: Where the Rocks Live

Everything changes once you cross the asteroid belt. The scale drops off a cliff. We go from giants to what are essentially cosmic pebbles.

Earth sits at the top of the rocky heap. We are the largest of the four terrestrial planets. Our diameter is about 7,917 miles (12,742 km). It sounds big until you remember Jupiter. On the scale of the order of planets by size, we are the big fish in a very small pond.

Why Earth and Venus are "Sisters"

Venus is almost the same size as Earth. It’s often called our sister planet because its diameter is only about 630 miles smaller than ours. If you stood on Venus (and somehow didn’t melt from the 900-degree heat or get crushed by the atmosphere), the gravity would feel almost identical to home. But size is where the similarities end. Venus is a runaway greenhouse nightmare.

The Shrinking Worlds: Mars and Mercury

Mars is surprisingly small. A lot of people think it's Earth-sized, but it’s actually only about half the width of Earth. Its diameter is roughly 4,212 miles. Because it’s so small, it lost its internal heat quickly and its core solidified, which meant it lost its magnetic field. Without that shield, the solar wind stripped away its atmosphere. This is a perfect example of how size dictates a planet’s destiny. If Mars were bigger, it might still have oceans today.

Finally, we have Mercury. It’s the runt of the litter. It’s barely larger than Earth’s Moon. In fact, some moons in our solar system—like Jupiter’s Ganymede and Saturn’s Titan—are actually bigger than Mercury. It’s a tiny, cratered ball of iron and rock that’s constantly getting blasted by the Sun. It’s so small and has such little gravity that it can’t hold onto a real atmosphere at all.

The Breakdown: The Order of Planets by Size (Diameter)

To keep it simple, here is how they stack up from largest to smallest. No fluff, just the raw hierarchy:

- Jupiter (86,881 miles / 139,820 km)

- Saturn (72,367 miles / 116,460 km)

- Uranus (31,518 miles / 50,724 km)

- Neptune (30,599 miles / 49,244 km)

- Earth (7,917 miles / 12,742 km)

- Venus (7,521 miles / 12,104 km)

- Mars (4,212 miles / 6,779 km)

- Mercury (3,032 miles / 4,879 km)

What Happened to Pluto?

You can't talk about the order of planets by size without addressing the icy elephant in the room. Pluto. In 2006, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) demoted Pluto to "dwarf planet" status. Why? Mostly because it's tiny. It’s smaller than the Moon. It’s even smaller than the United States is wide.

But it wasn't just size. It was the fact that astronomers started finding other things out there in the Kuiper Belt—like Eris—that were similar in size or even heavier. If Pluto was a planet, then we’d have to have dozens of planets. To keep the textbooks manageable, the IAU created a new definition. To be a "real" planet, you have to clear your orbit of other debris. Pluto lives in a crowded neighborhood, so it lost its spot in the main lineup.

Why Does This Hierarchy Matter?

This isn't just trivia for a pub quiz. The size of a planet tells us about the history of the solar system. During the "Grand Tack" model—a theory about the early movements of the planets—Jupiter moved inward toward the Sun and then back out again. Its massive gravity acted like a cosmic snowplow, clearing out material and potentially preventing Mars from growing any larger.

Basically, we live in a neighborhood shaped by giants. The fact that Earth is the largest of the rocky planets is likely one of the reasons we have a thick enough atmosphere and a stable enough climate to support life.

Practical Steps for Visualizing the Scale

If you really want to wrap your head around this, stop looking at posters. Try these activities to get a sense of the "real" order of planets by size:

- The Fruit Scale: Grab a watermelon (Jupiter), a large grapefruit (Saturn), two apples (Uranus and Neptune), two cherry tomatoes (Earth and Venus), a blueberry (Mars), and a single peppercorn (Mercury). This puts the volume in perspective way better than a drawing.

- Virtual Mapping: Use tools like If the Moon Were Only 1 Pixel. It’s a mind-bending website that forces you to scroll through the empty space between these objects.

- Stargazing: Look for Jupiter and Saturn through a basic telescope. Even at low magnification, you can see the physical disk of Jupiter versus the "point" of a star. You can actually see its girth.

The solar system isn't a neat, balanced place. It’s a collection of a few monsters and a handful of dust motes. We just happen to live on the biggest dust mote there is.

Next Steps for Your Space Journey:

Check out the current night sky map to see which of the giants are visible this month. Jupiter is often the brightest "star" in the sky, and knowing its true scale makes seeing it through a pair of binoculars a completely different experience. You can also dive into the "mass vs. volume" debate to see why Neptune is the weird outlier in the size rankings.