Ever stared at a goldfish and wondered what’s actually keeping that tiny thing ticking? It’s easy to assume that because fish are complex, swimming, eating machines, they’ve got a ticker similar to ours. We have four chambers. They’re basically the gold standard of high-performance cardiac engineering. But when you ask how many chambers in a fish heart, the answer is actually just two.

Wait. Only two?

It sounds primitive. It sounds like it shouldn't work for a tuna chasing down prey at 40 miles per hour or a shark prowling the deep. But evolution isn't always about adding more parts; it's about efficiency within a specific environment. Fish live in a world of buoyancy and gills, not gravity and lungs. That single change in environment changes everything about how blood needs to move.

The Basic Anatomy of a Two-Chambered System

In the simplest terms, a fish heart consists of an atrium and a ventricle. If you were to look at it under a microscope—something researchers like those at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography do regularly—it wouldn't look like the "heart shape" you see on Valentine's cards. It’s more like a folded tube.

Blood comes in through a thin-walled reservoir called the sinus venosus. Think of this as the waiting room. From there, it flows into the atrium, which is the first official chamber. The atrium narrows down and pushes the blood into the ventricle, the heavy lifter. This second chamber is thick-muscled and tough. It has to be. Its job is to pump that blood with enough force to reach the gills.

But there’s a catch.

Because there are only two chambers, the blood only passes through the heart once per circuit. In humans, blood goes to the heart, then the lungs, back to the heart, and then out to the body. That’s a "double circuit." Fish use a "single circuit."

The blood goes: Heart → Gills → Body → Heart.

This means by the time the blood reaches the fish's tail or its brain, the pressure has dropped significantly. It’s a low-pressure system. It’s chill. It works perfectly fine for a creature that doesn't have to fight the constant crushing pull of gravity as much as a land mammal does.

Why the Number of Chambers Actually Matters

You might wonder why nature didn't just give them three or four chambers anyway. Well, energy is expensive. Growing and maintaining a four-chambered heart requires a massive amount of metabolic "rent."

Fish are mostly ectothermic. You probably know them as cold-blooded. Because they don't need to generate internal heat to keep their bodies at a constant 98.6 degrees, their oxygen demands are lower. A two-chambered heart provides exactly enough oxygen to keep the lights on without wasting energy.

🔗 Read more: How Coca-Cola’s Santa Claus Actually Changed Christmas

However, there is an exception to the "two-chamber" rule that messes with everyone’s head. Lungfish.

These weird, ancient survivors have a heart that is starting to look like it’s trying to become a three-chambered one. They have a partial septum, which is basically a divider in the atrium. Why? Because they breathe air. As soon as a creature starts dealing with lungs, the plumbing has to get more complicated to keep oxygenated blood from mixing too much with the "used" deoxygenated blood. It’s a living transition of evolutionary history right in their chest.

The Secret "Bonus" Chambers

If you want to get technical—and biologists usually do—many people argue that a fish heart actually has four structures, even if only two are called "chambers."

- Sinus Venosus: The entry point.

- Atrium: Chamber one.

- Ventricle: Chamber two.

- Bulbus Arteriosus: The exit ramp.

In sharks and other cartilaginous fish, that exit ramp is called the conus arteriosus. It’s got valves to prevent backflow. Is it a chamber? By the strictest medical definition used for mammals, no. But it is a vital component of the pump. It helps dampen the "pulse" of the blood so it doesn't shred the delicate capillaries in the gills. Gills are incredibly fragile. If the ventricle pumped blood directly into them with raw, undampened force, the fish would essentially have a stroke in its breathing organs.

Comparing the Ticker: Fish vs. The Rest of the World

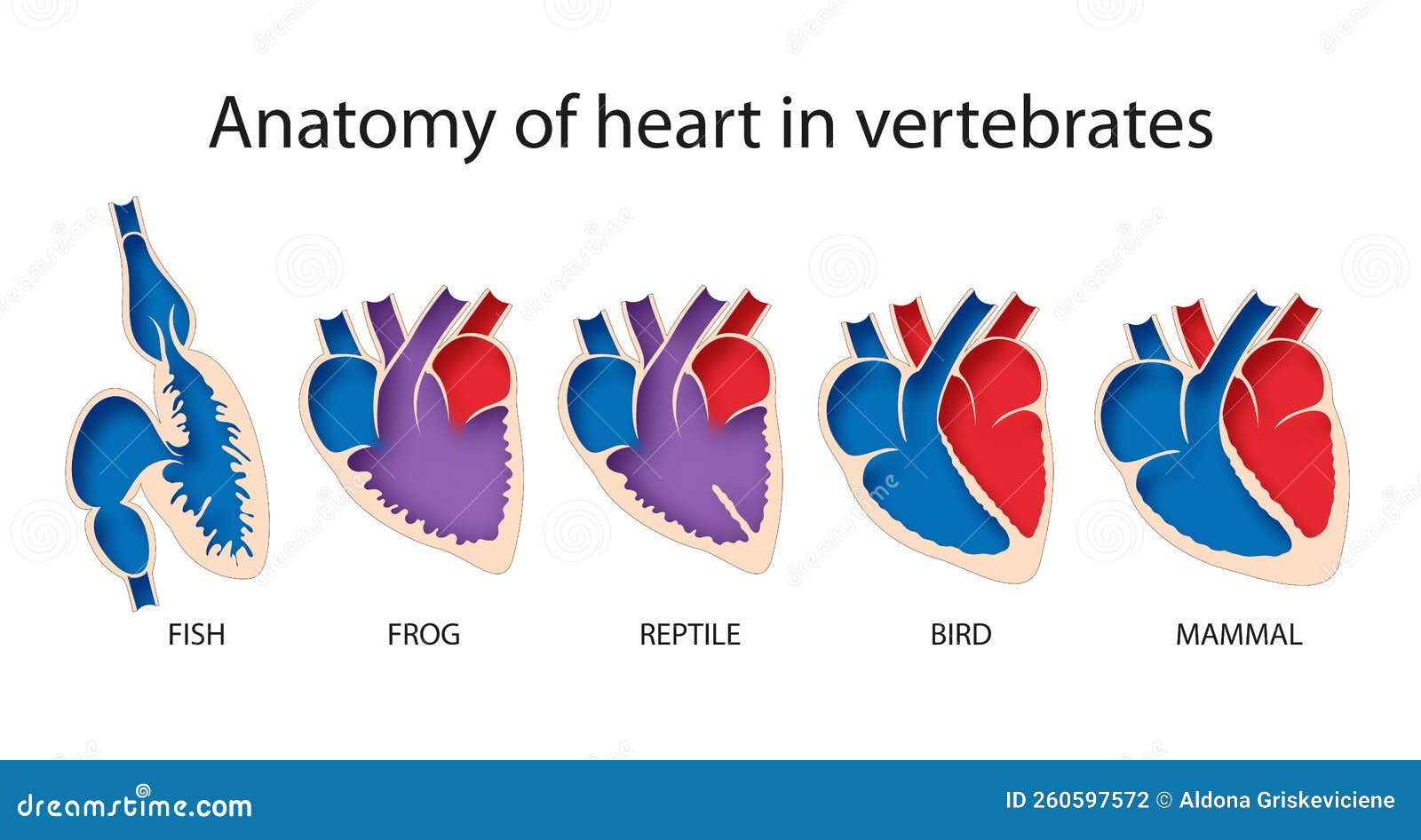

Looking at the animal kingdom shows a clear ladder of complexity.

💡 You might also like: Harvest Bible Chapel in Elgin: What Most People Get Wrong About the Post-MacDonald Era

- Fish: 2 chambers. Single circuit.

- Amphibians: 3 chambers (two atria, one ventricle). Double circuit, but the blood mixes in the middle.

- Reptiles: 3 chambers (mostly), but they’ve got a partial wall in the ventricle to keep things more organized.

- Birds and Mammals: 4 chambers. Total separation. Maximum efficiency for high-octane living.

When you see it laid out like that, you realize the fish heart isn't "bad." It’s just the foundation. It’s the "OG" design.

The High-Performance Outliers

Nature loves a rebel. Let's talk about Tuna and Great White Sharks.

These guys are partially endothermic (warm-blooded). They can keep their muscles warmer than the surrounding water, which makes them faster and meaner. Because of this, their two-chambered hearts are massive relative to their body size. A Bluefin Tuna’s heart is a powerhouse. Even though it's still technically a two-chambered setup, it operates at pressures that would make a trout's heart explode.

They have more "compact" myocardium—the actual muscle tissue of the heart. Most fish have "spongy" heart muscle that gets oxygen from the blood passing through the chambers. High-performance fish have their own coronary arteries that supply the heart muscle itself with fresh oxygen, just like ours do.

What This Means for Your Aquarium

If you're a hobbyist, understanding how many chambers in a fish heart isn't just trivia. It’s about survival.

Because fish have a low-pressure, single-circuit system, they are extremely sensitive to dissolved oxygen levels in the water. If the oxygen in the tank drops, the heart has to work overtime, but it doesn't have the "turbocharge" capabilities of a human heart.

When a fish is stressed, you’ll see its operculum (gill covers) moving faster. That’s the fish trying to compensate for its heart's physical limitations. It can only pump so much blood per minute. If the oxygen isn't in the water, the heart can't magically find more.

Actionable Insights for the Curious

- Observe Respiratory Rate: If you have pet fish, count the gill movements when they are resting versus after feeding. This is the best way to "see" their heart at work.

- Maintain Oxygenation: Since the two-chambered system is less efficient at high-speed recovery, ensure your tank has adequate surface agitation. This is where the gas exchange happens that keeps that two-chambered pump from failing.

- Thermal Stress Awareness: Remember that as water gets warmer, it holds less oxygen. For a fish with a two-chambered heart, warm water is a double whammy: it speeds up their metabolism (requiring more oxygen) while providing less of it.

- Study Evolution: If you're interested in biology, look up the "septum" development in lungfish. It’s the closest thing we have to a "missing link" in cardiac evolution.

The two-chambered heart is a masterpiece of "enough." It’s a reminder that in nature, you don't need the most complex gear to be the king of your domain. You just need the right gear for the zip code you live in.