Most people think nuclear power is some kind of magic or a sci-fi mystery. Honestly, it’s basically just a really high-tech way to boil water. That sounds underwhelming, doesn't it? But when you strip away the cooling towers and the radiation suits, a nuclear reactor is just a heat source. It’s a kettle. A very, very powerful, carbon-free kettle that runs on the fundamental tension of the universe.

The core question of how do nuclear power plants work isn't about explosions or green glowing goo. It’s about heat. In a coal plant, you burn rocks to get heat. In a gas plant, you burn methane. In a nuclear plant, you split atoms. This process, called fission, releases a staggering amount of energy from a tiny amount of fuel. If you’ve ever wondered why we don't just use solar or wind for everything, the answer usually lies in the sheer energy density of uranium-235. A single ceramic pellet of uranium—about the size of your fingertip—contains as much energy as a ton of coal. That's not a typo. One ton.

The Engine Room: Splitting the Unsplittable

At the heart of every nuclear plant is the reactor core. Inside this steel pressure vessel, we aren't just letting things happen randomly. We’re orchestrating a subatomic ballet. You take a heavy, slightly unstable atom like Uranium-235. You hit it with a neutron. The uranium atom gets "fat" and unstable, then it wobbles and splits into two smaller atoms.

When it splits, it does two things that change the world. First, it releases a massive burst of kinetic energy that turns into heat. Second, it spits out two or three more neutrons. Those neutrons go on to hit other uranium atoms. If you have enough uranium packed together—what engineers call "critical mass"—you get a chain reaction.

Controlling the Fire

You can't just let the reaction run wild. That’s a bomb, not a power plant. To keep things steady, we use control rods. These are usually made of materials like boron or cadmium, which act like "neutron sponges." If the reactor gets too hot or the reaction picks up too much speed, operators drop these rods into the core. They soak up the neutrons, and the "fire" dies down.

It’s a delicate balance. If you pull the rods out, the power goes up. Push them in, it goes down. Modern plants, like the AP1000 designed by Westinghouse, use passive safety systems. This means they don't even need an operator or a pump to move the rods if something goes wrong; gravity or natural pressure does it for them. It's a "fail-safe" design that addresses many of the fears people have held since the 1970s.

🔗 Read more: Is This Essay AI Generated? What Most People Get Wrong About Detection

The Three Loops: Keeping the Radiation Where It Belongs

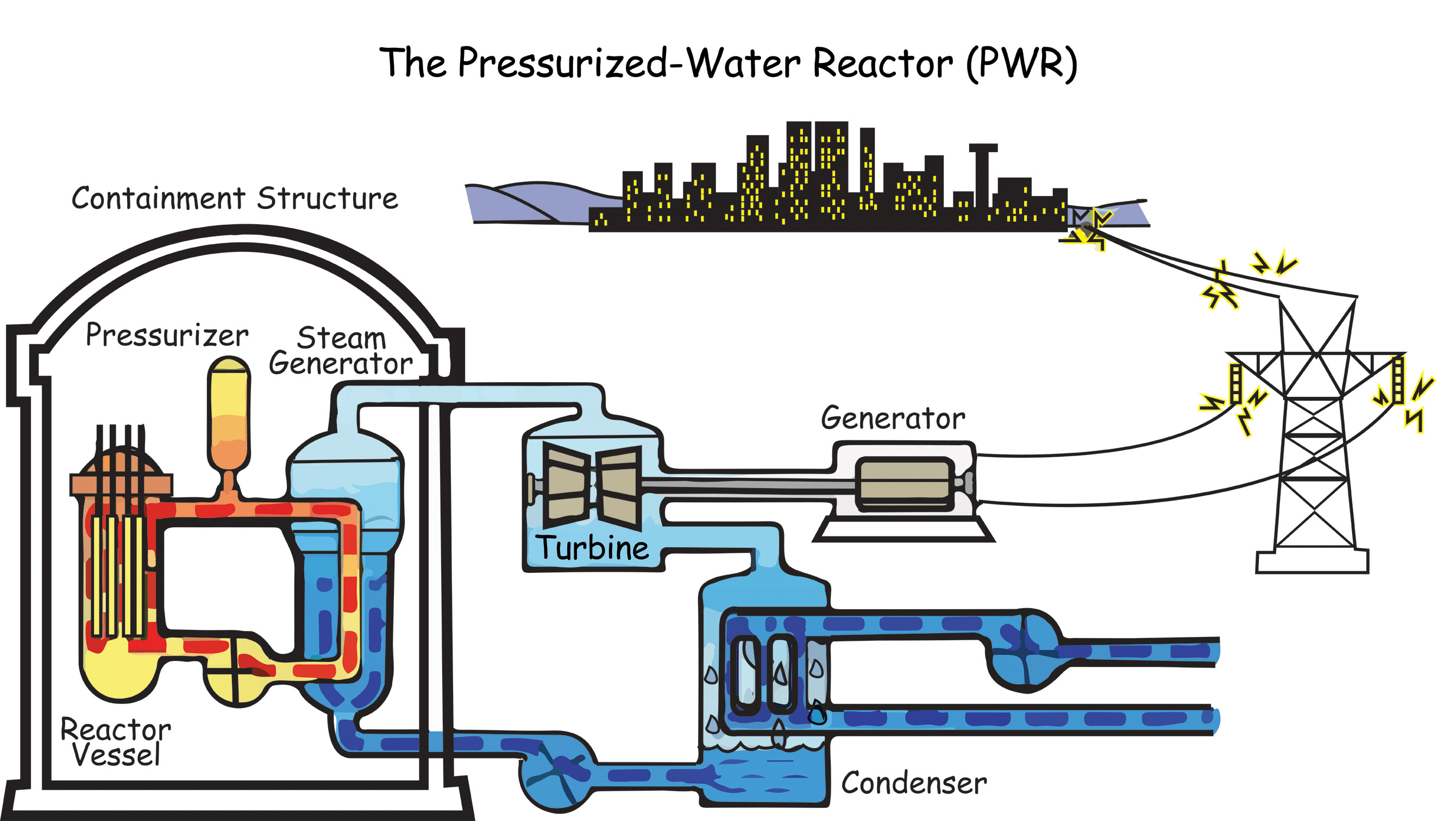

A huge misconception about how do nuclear power plants work is that the water coming out of those big cooling towers is radioactive. It isn't. In fact, that's just steam. Pure H2O. To keep things safe, most plants (especially Pressurized Water Reactors, or PWRs) use three separate loops of water that never actually touch each other.

- The Primary Loop: This water touches the reactor core. It gets incredibly hot—over $300°C$ ($572°F$)—but it doesn't boil because it's kept under extreme pressure. It circulates through the core, picks up the heat, and moves to a heat exchanger.

- The Secondary Loop: This is where the magic happens. The super-hot water from the primary loop passes through thousands of tiny tubes inside a steam generator. The water in the secondary loop touches the outside of these tubes, boils into steam, and rushes off to spin a turbine.

- The Tertiary (Cooling) Loop: Once the steam has spun the turbine, it needs to be turned back into water so it can be reused. This loop pulls cold water from a river, lake, or ocean to cool the steam down. This is the water you see evaporating from those iconic curved towers.

The separation is key. The water that sees the radiation stays locked in a closed cycle inside the containment building. The water that turns the turbine is clean. The water that goes back to the river is just slightly warmer than when it arrived.

Why Uranium?

Why don't we use something else? Well, we are trying. Scientists are looking at Thorium, which is more abundant and harder to turn into weapons. But Uranium-235 is the gold standard because it's "fissile." It’s ready to split.

The fuel isn't just tossed into the reactor like logs on a fire. It’s processed into those ceramic pellets I mentioned, which are then stacked into long metal tubes called fuel rods. Bundles of these rods stay in the reactor for about 18 to 24 months. Eventually, the "fizz" wears off. The uranium has split into so many other elements that it can't sustain the reaction efficiently anymore. This is what we call "spent fuel." It's still hot, and it's still radioactive, which brings us to the most debated part of the whole industry.

💡 You might also like: How Many Years is a Lightyear in Miles: The Math Behind the Misconception

The Waste Problem and the Safety Reality

Let's be real: the "waste" issue is the elephant in the room. When you're done with the fuel, it sits in deep pools of water for a few years to cool down. After that, it’s moved to "dry casks"—massive concrete and steel containers.

According to the Nuclear Energy Institute, all the used nuclear fuel produced by the U.S. nuclear energy industry over the last 60 years could fit on a single football field at a depth of less than 10 yards. It’s not a lot of physical stuff, but it stays dangerous for a long time. Some countries, like France (which gets about 70% of its electricity from nuclear), recycle their spent fuel to squeeze more energy out of it. The U.S. currently doesn't, mostly due to policy and cost, not physics.

As for safety, the data is often surprising. When you look at "deaths per terawatt-hour," nuclear is consistently one of the safest energy sources on the planet—often safer than wind (where people fall off turbines) or rooftop solar (where people fall off roofs). This is because when something goes wrong in a nuclear plant, it's a global news event. When a coal plant releases particulate matter that causes asthma and lung disease, it’s just a Tuesday.

The Future: Small Modular Reactors (SMRs)

The giant, billion-dollar plants of the past are becoming harder to build. They take too long. They cost too much. The new frontier in understanding how do nuclear power plants work is the SMR.

Companies like NuScale and TerraPower (backed by Bill Gates) are designing reactors that can be built in a factory and shipped to a site on a truck. These are smaller, simpler, and theoretically much cheaper. They use "molten salt" or "liquid metal" instead of water as a coolant in some cases, which allows them to operate at lower pressures and even higher safety margins. It’s a complete shift in how we think about the grid. Instead of one massive plant powering a whole state, you might have ten small ones tucked away near industrial centers.

Actionable Insights for the Energy-Conscious

If you're looking to understand the role of nuclear in our transition to clean energy, keep these practical points in mind:

- Check your local mix: Use a tool like Electricity Maps to see if your home is currently powered by nuclear. If you live in Illinois, Pennsylvania, or South Carolina, there’s a high chance your lights are on because of fission right now.

- Support Life Extensions: Most carbon-reduction goals depend on keeping existing nuclear plants open. Many plants are being licensed to run for 60 or even 80 years. This is often the cheapest way to keep carbon emissions down.

- Follow the SMR projects: Watch the progress of the Natrium project in Wyoming. It's a real-world test of whether the next generation of "nuclear kettles" can actually be built on time and on budget.

- Understand the "Baseload" concept: Solar and wind are great, but they fluctuate. Nuclear provides "baseload" power—a steady, unmoving floor of electricity that keeps the hospital machines running when the wind stops blowing at 3 AM.

Nuclear power isn't a perfect solution, but it is a powerful one. By understanding the simple physics of the three-loop system and the reality of energy density, we can have a much more honest conversation about what our grid should look like in 2030 and beyond. It's not about being "pro-nuclear" or "anti-nuclear"—it's about being pro-math. And the math says we need a lot of heat to run a modern world.