Honestly, the first time you watch the house of games movie, you feel like you’re the smartest person in the room. You’re tracking the tells. You’re watching Joe Mantegna’s smooth-talking Mike and thinking, "Okay, I see what he’s doing." Then the floor drops out.

That’s the David Mamet magic.

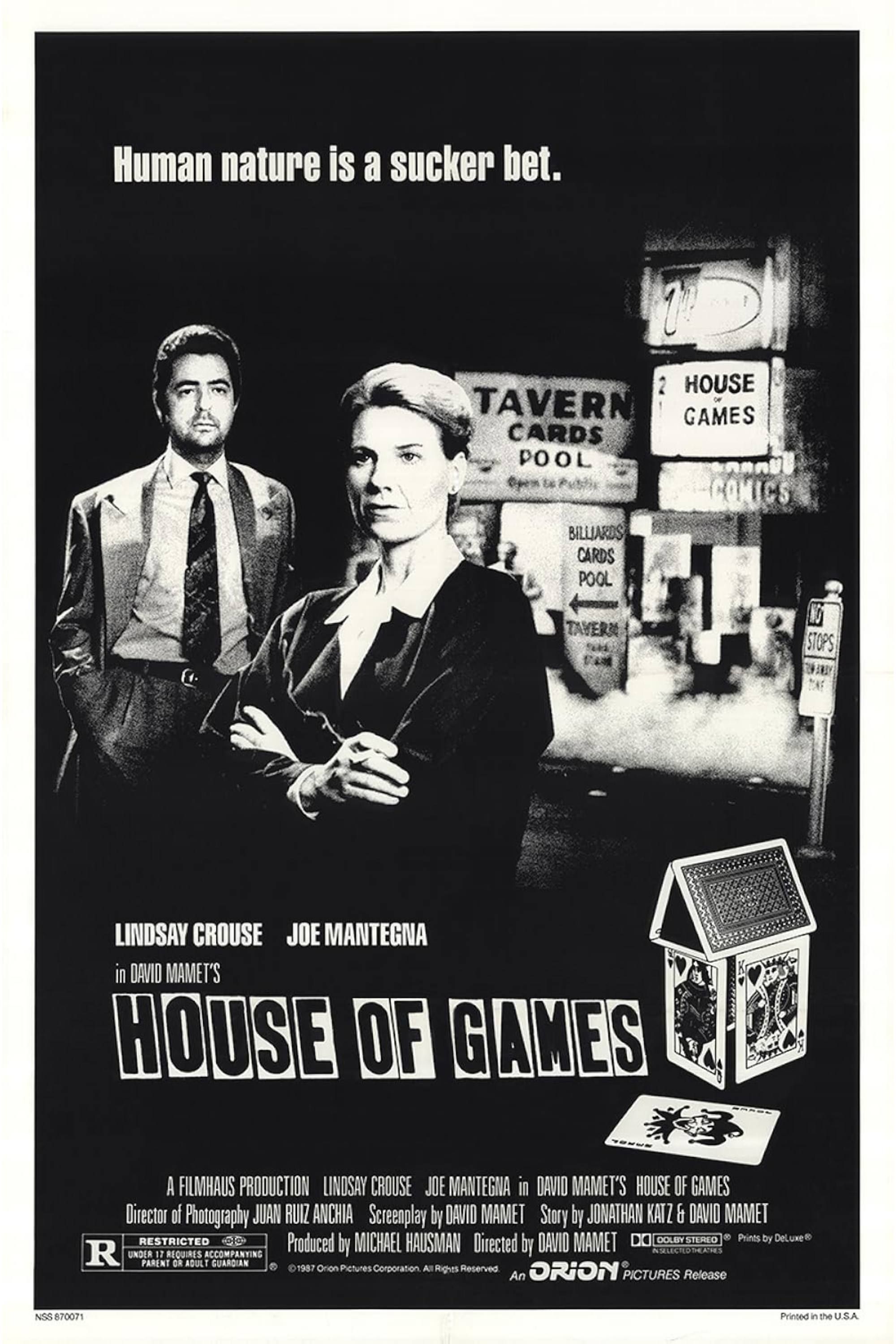

Released in 1987, this flick wasn't just another 80s thriller. It was a playwright’s bold, weird, and incredibly disciplined leap into cinema. Mamet, fresh off a Pulitzer for Glengarry Glen Ross, decided he wanted to show us how a "con" actually works—not the Hollywood version, but the cold, psychological machinery of it. It’s a movie about the lies we tell ourselves while someone else is busy stealing our watch.

The Setup: A Shrink Walks Into a Dive Bar

The plot kicks off with Dr. Margaret Ford, played by Lindsay Crouse. She’s a high-achieving psychiatrist and a best-selling author, but she’s bored out of her mind. She’s got a patient, Billy Hahn, who says he’s going to kill himself because he owes money to a bookie.

Margaret, in a mix of professional arrogance and genuine concern, decides to go confront the bookie. This leads her to a seedy backroom called the House of Games. This is where she meets Mike (Joe Mantegna).

Mike is everything Margaret isn't: spontaneous, dangerous, and totally comfortable in the shadows. He tells her the debt isn't that big of a deal, but then he offers her a deal. He wants her to help him spot a "tell" in a high-stakes poker game. He says his opponent has a habit of fiddling with a ring when he’s bluffing.

She agrees. She’s hooked. The audience is hooked. We think we’re watching a movie about a woman learning the ropes of the underworld. In reality, we’re the marks.

📖 Related: Emily Piggford Movies and TV Shows: Why You Recognize That Face

Why the Dialogue Sounds So... Different

If you’ve never seen a Mamet film, the talking might throw you. It’s not naturalistic. It’s stilted. Rhythmic. It’s what critics call "Mamet-speak."

In the house of games movie, people don't talk like they’re at a grocery store. They talk like they’re playing chess with words. Every "it’s a deal" or "you’re a bad pony" is deliberate. Mamet was a theater guy first, and he brought that stage precision to the screen.

- Joe Mantegna is the king of this style. He delivers lines with a flat, cool precision that makes you hang on every syllable.

- Ricky Jay, a real-life magician and expert on deceptions, plays a gambler named George. His presence adds a layer of authenticity because the guy actually knew how to manipulate people's perception in real life.

- Lindsay Crouse plays Margaret with a certain stiffness, which some viewers find jarring, but it perfectly mirrors her character’s repressed, academic nature trying to fit into a world of street-smart predators.

The "Tell" That Everyone Misses

Roger Ebert famously loved this movie. He gave it four stars and called it the best film of 1987. He pointed out something brilliant: the movie is "awake." While most thrillers are just going through the motions, this one is actively trying to outthink you.

There’s a scene where Mike explains the "Basic Principle" of the con. He says, "It’s called a confidence game. Why? Because you give me your confidence? No. Because I give you mine."

Think about that.

The con artist isn't the one who needs to be trusted; he’s the one who pretends to trust you. By letting Margaret into his world—showing her the "secrets" of how they trick people—Mike makes her feel special. He makes her feel like an insider. That’s the ultimate hook. Once you think you’re in on the joke, you’ve already lost.

👉 See also: Elaine Cassidy Movies and TV Shows: Why This Irish Icon Is Still Everywhere

Technical Sleight of Hand

The look of the movie is pure neo-noir. Cinematographer Juan Ruiz Anchía uses deep shadows and a lot of browns and greys. It feels claustrophobic. Most of the action happens at night or in windowless rooms.

The music, composed by Alaric Jans, is minimalist. It doesn’t tell you how to feel with big orchestral swells. Instead, it just hums in the background, keeping the tension tight.

Interesting fact: The movie only made about $2.6 million at the box office. It was a "small" film by 1980s standards, but its legacy is huge. It basically paved the way for every "twist" movie that followed, from The Usual Suspects to Inception.

The Psychology of the Mark

What really makes the house of games movie stick in your brain is the question of why Margaret stays. She’s rich. She’s successful. She could walk away at any time.

But she doesn't.

She has a "biological need to confront the unknown," as some critics put it. She’s addicted to the thrill of the deception. In a way, she’s no different from her gambling patient. She just hides it under a Harvard degree and a tailored suit. The movie suggests that we all have a bit of the "mark" in us. We want to believe the lie because the lie is more exciting than our real lives.

✨ Don't miss: Ebonie Smith Movies and TV Shows: The Child Star Who Actually Made It Out Okay

What Most People Get Wrong

People often debate the ending. Some think Margaret is a victim; others think she’s a monster. Without giving away the final, brutal twist, let’s just say that by the time the credits roll, the line between the "good" doctor and the "bad" con man has completely evaporated.

The biggest misconception is that this is just a movie about card tricks. It’s not. It’s a movie about the transfer of power. Every interaction is a transaction.

Key Lessons from the House of Games

If you're looking to understand the mechanics of this film or apply its "lessons" to how you watch movies, keep these specific points in mind:

- Watch the background: In Mamet films, the staging often tells you more than the dialogue. Notice how characters are positioned in the frame—who is "dominating" the space?

- Ignore the "secrets": When Mike explains a small con, like the "twenty-dollar bill" trick, he’s distracting you from the larger game. In a con, the information you're given is always the bait.

- Check the cadence: Listen for when characters repeat each other. In Mamet's world, repetition usually means someone is trying to gain control or is being led into a trap.

Ready to Play?

If you haven't seen the house of games movie in a few years, it’s worth a re-watch. You’ll notice things you missed. You'll see the "tells" that were right in front of your face the first time.

To get the most out of your next viewing, pay close attention to the very first scene with the two women outside the bookstore. It sets the tone for everything that follows regarding how we perceive "truth" versus "performance."

If you're a fan of the genre, you might also want to look into Mamet’s other work like The Spanish Prisoner or his screenplay for The Verdict. They all play in this same sandbox of moral ambiguity and verbal gymnastics.

Just remember Mike’s advice: "Don't trust anybody." Especially not the director.

Next Steps for the Viewer

- Track the "Golden Rule": Watch the film again and see if you can find the exact moment Margaret stops being a doctor and starts being a thief.

- Analyze the Dialogue: Pick one scene and count how many times a character answers a question with another question—it’s a classic Mamet power move.

- Compare to Modern Noir: Watch this alongside something like Nightcrawler or Drive to see how the "expressionless" acting style evolved over forty years.