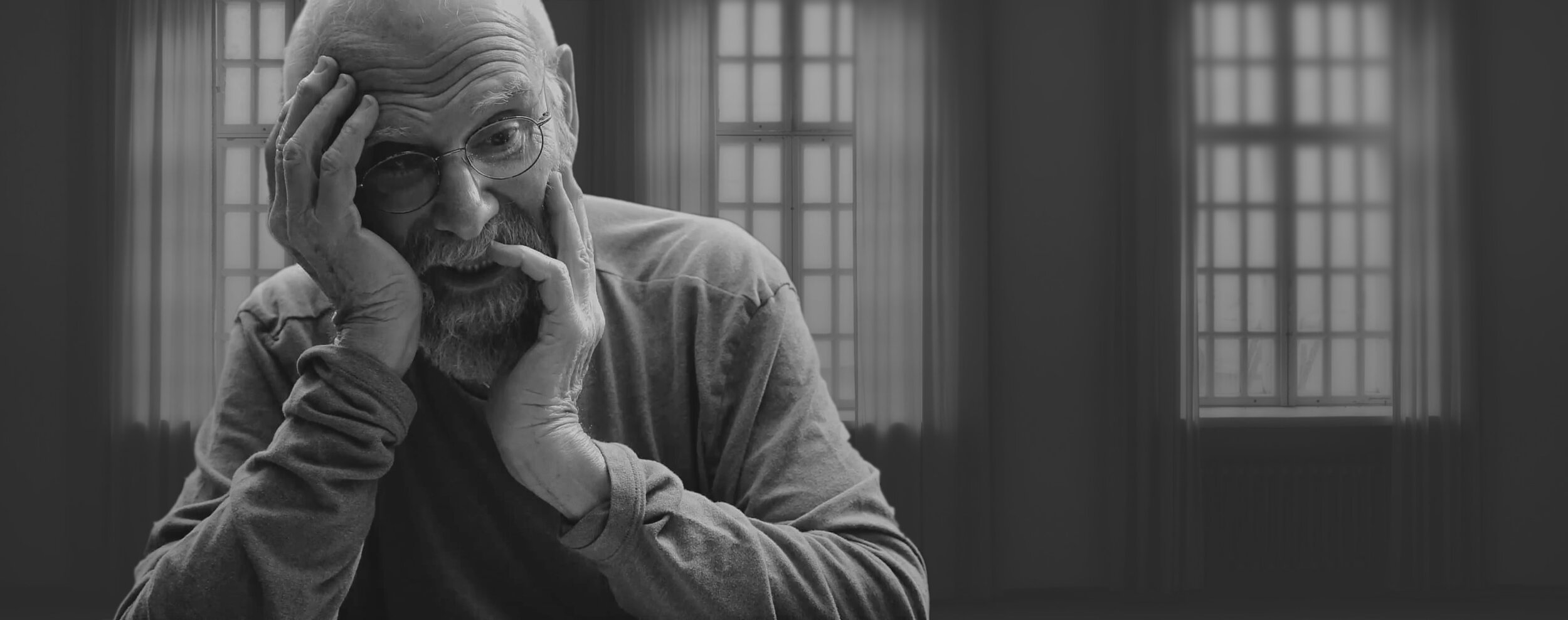

You’re sitting in a quiet room, maybe nursing a cup of tea, and suddenly a giant blue spider skitters across the floor. Or maybe you hear your name called from an empty hallway. Most people immediately jump to one terrifying conclusion: "I’m losing my mind." But if you’ve ever read Hallucinations by Oliver Sacks, you know that’s usually not the case. Sacks, the legendary neurologist who basically spent his life humanizing the "weird" stuff our brains do, argues that hallucinations aren’t just symptoms of madness. They are actually a fundamental part of being human.

It's a trip.

The book is less of a dry medical textbook and more of a collection of strange, beautiful, and sometimes spooky stories. Sacks writes about people who see elaborate patterns, tiny people in Victorian dress, or even ghosts of deceased spouses. And the kicker? Most of these people are totally sane. They know the visions aren't real, but their brains are projecting them anyway with the HD clarity of a 4K television.

🔗 Read more: How many calories are in a pepper: The real numbers for every variety

Honestly, our brains are just incredibly restless. When they don't get enough input from the outside world, they start making their own entertainment.

The Charles Bonnet Syndrome: When Sight Goes Dark, the Brain Lights Up

One of the most fascinating things Sacks explores is Charles Bonnet Syndrome (CBS). Imagine you’re losing your vision due to macular degeneration or cataracts. You’d expect the world to just get dimmer, right? Well, for many, the opposite happens. The visual cortex, suddenly deprived of its usual "feed" from the eyes, starts firing off randomly.

It gets bored. So, it hallucinates.

Sacks tells the story of Rosalie, an elderly woman in a nursing home who started seeing people in colorful Eastern dress walking through her room. She wasn't schizophrenic. She wasn't demented. She was just partially blind. This is actually way more common than doctors used to think. When the brain doesn't get data, it dips into its own archives and starts "broadcasting" images.

Think of it like a radio that produces static when it's between stations. Only, instead of white noise, your brain produces a detailed image of a silent man in a top hat standing in your kitchen.

What’s wild is that these hallucinations are almost always silent. They don't interact with the person. They just... exist. Sacks noted that for patients like Rosalie, the real tragedy wasn't the visions—it was the fear of being labeled "crazy" if they told anyone. By bringing this into the light, Sacks changed the way we look at vision loss entirely.

Migraines and the Geometry of the Mind

If you've ever had a "classic" migraine, you might have seen shimmering zig-zags or weird, growing blind spots. These are "auras," and they are technically hallucinations. Sacks himself suffered from these for years. He describes seeing "fortification patterns"—complex, geometric shapes that look like the bird's-eye view of an ancient fort.

Why geometry?

Because our visual cortex is organized in layers and columns that are literally wired to detect lines, angles, and borders. When a migraine "storm" passes over these neurons, it triggers them in a specific order. You’re not just seeing a random shape; you’re seeing the literal architecture of your own primary visual cortex. It’s like the brain is taking a selfie of its own internal wiring.

Sacks points out that these geometric patterns have influenced art for centuries. From the intricate tile work in Islamic mosques to the psychedelic art of the 60s, these "entoptic" visions—stuff generated inside the eye or brain—have shaped human culture. We aren't just imagining things; we are reflecting the physical structure of our nervous systems.

The Heavy Toll of Parkinson’s and L-Dopa

In Hallucinations by Oliver Sacks, he doesn't shy away from the darker side of neurology. He spent a lot of time working with Parkinson’s patients, many of whom experience hallucinations either because of the disease itself or as a side effect of the drug L-Dopa.

These aren't usually geometric patterns. They are "presence" hallucinations.

You feel someone standing just behind your shoulder. You turn, and no one is there. Or you see a small animal dart under a chair. For some, these visions can become quite elaborate and even frightening. Sacks describes the delicate balance doctors have to strike: give enough medication to help the patient walk, but not so much that they start seeing demons in the drapes. It’s a tightrope walk over a very strange abyss.

The Drugs: Sacks’ Own Experiments

Let’s be real—part of why this book is so popular is because Oliver Sacks was a bit of a "psychonaut" back in the day. In the chapter "Altered States," he talks about his own experiences with everything from LSD to morning glory seeds and Artane.

One particular story stands out.

After taking a hefty dose of Artane (a synthetic drug), Sacks had a full-blown conversation with his friends, Jim and Kathy, while they were eating breakfast at his house. They talked for quite a while. Then, he went to the kitchen to get more coffee, came back, and realized Jim and Kathy were never there. They weren't even in the country.

He was talking to the air.

He describes the experience with a sort of clinical detachment that makes it even more jarring. He wasn't looking for a "high" in the traditional sense; he was a scientist using his own brain as a laboratory. He wanted to know how these chemicals changed the perception of time and space. He realized that drugs don't just "add" hallucinations; they often remove the filters that keep our subconscious from leaking into our conscious reality.

The Ghost in the Room: Bereavement and the "Sense of Presence"

Maybe the most touching part of the book is when Sacks discusses the hallucinations of the bereaved. After losing a spouse of 40 or 50 years, it is incredibly common for the survivor to hear the front door open at 5:00 PM, or hear their partner's voice in the next room.

Sometimes they see them sitting in their usual chair.

These aren't signs of a breakdown. They are the brain’s way of mourning. The neural pathways associated with that person are so deeply etched into the brain that they don't just disappear when the person dies. The brain keeps "expecting" the input, and when it doesn't get it, it generates it. Sacks treats these stories with immense tenderness. He argues that these hallucinations can actually be quite comforting, a final "bridge" between the living and the dead.

Why We Should Stop Being Afraid

The overarching theme of Hallucinations by Oliver Sacks is that the line between "normal" and "hallucinating" is much thinner than we like to admit.

- Hypnagogic Hallucinations: Those weird sounds or images you see right as you’re falling asleep? Totally normal.

- Sensory Deprivation: Stick a healthy person in a pitch-black, silent room for long enough, and they will start seeing things.

- High Fever: Delirium is just the brain's processing unit overheating and throwing errors.

We tend to associate hallucinations exclusively with schizophrenia, but in reality, millions of people experience them due to sleep deprivation, stress, grief, or simple sensory issues. Sacks’ goal was to "de-stigmatize" the experience. He wanted us to see these episodes as a window into the brain’s incredible creative power.

What to Do If It Happens to You

If you or someone you know starts seeing things that aren't there, the first step isn't to panic. It’s to look at the context.

First, check the medications. Many common drugs—for blood pressure, sleep, or Parkinson’s—can trigger visions. Second, check the senses. Is there a hearing or vision loss issue? Often, getting a better pair of glasses or a hearing aid can "starve" the hallucinations by providing the brain with real data.

Third, talk about it. Sacks found that the greatest burden for his patients was the secrecy. Once they realized they weren't "crazy," the fear vanished. And when the fear vanishes, the hallucinations often become much less intrusive.

Practical Takeaways from Sacks' Research

If you are dealing with hallucinations or just curious about the mind, here is how to apply the insights from Sacks' work:

- Distinguish Between Insight and Delusion: A hallucination is seeing something that isn't there. A delusion is believing it's real even when you're shown proof it isn't. If you know the blue spider isn't real, you have "insight," which is a very good sign neurologically.

- Audit Your Sleep and Stress: The vast majority of "ghostly" sightings and strange sounds happen during periods of extreme exhaustion or right at the edge of sleep (hypnopompic or hypnagogic states). Fix the sleep, and the "ghosts" usually move out.

- Consult a Neurologist, Not Just a Psychiatrist: If hallucinations start suddenly, it could be a simple "misfire" in the sensory cortex rather than a mental health crisis. Always rule out physical causes like migraines, epilepsy, or CBS first.

- Embrace the Brain's Complexity: Understand that your brain is an active creator of your reality, not just a passive recorder. Sometimes, it just gets a little too creative.

Sacks’ work reminds us that our internal world is far more complex than we give it credit for. Whether it's a migraine aura or a voice in the wind, these experiences are just another part of the weird, wonderful tapestry of human consciousness. Instead of fearing the "glitches" in our biological software, we can view them as a rare glimpse into the engine room of the mind.

Explore your environment for sensory triggers. Often, low-light conditions or repetitive white noise (like a fan) provide the "seed" for the brain to construct a hallucination. Brightening a room or changing the acoustic environment can often stop a visual or auditory hallucination in its tracks by forcing the brain to process clear, unambiguous data. For those living with Charles Bonnet Syndrome, simple eye-movement exercises—moving the eyes rapidly back and forth—can sometimes "reset" the visual cortex and clear the phantom images. Knowledge of the mechanism is often the best medicine for the anxiety that accompanies these experiences.