You’ve probably seen the letters on fraternity houses or in a high school geometry textbook. Maybe you’ve stared at a math problem and wondered why on earth a little squiggle called "zeta" is ruining your afternoon. But the Greek alphabet and sounds are way more than just symbols for sorority sweatshirts or physics variables. They are the literal DNA of Western literacy. If you’ve ever spoken English, you’re basically speaking a distant, slightly confused cousin of Greek.

Greek isn't just one thing. It's a living, breathing history lesson. Most people think the letters have stayed the same since Homer was shouting poems about the Trojan War. They haven't. The way an Ancient Athenian pronounced "beta" is drastically different from how a modern-day barista in Athens says it today. It's the difference between a hard "B" and a soft, buzzy "V."

Let's get into why this matters.

📖 Related: Starbucks Veranda K Cups: Why This Mellow Roast Actually Works

The Evolution of the Greek Alphabet and Sounds

The first thing you have to wrap your head around is that the Greeks didn't just invent these letters out of thin air. They "borrowed" (read: took) the Phoenician script around the 8th century BCE. The Phoenicians had a great system for consonants, but they didn't really bother with vowels. The Greeks, being the analytical types they were, realized that was a problem. They took some Phoenician letters that represented sounds Greek didn't have and repurposed them into vowels like Alpha and Epsilon.

This was a massive deal. Honestly, it changed everything. It made the Greek alphabet and sounds the first true alphabet where every sound—vowels and consonants—had a dedicated symbol.

Why the Sounds Changed

If you go to a classical Greek class today, they use what’s called Erasmian pronunciation. It’s named after Desiderius Erasmus, a 16th-century scholar who guessed how the ancients sounded. Spoiler: he was probably off. He thought "beta" sounded like the "B" in "ball." In Modern Greek, it’s "vita," and it sounds like the "V" in "vote."

Language is messy. Over 2,500 years, the sounds drifted. Vowels that used to be distinct started sounding exactly the same. This is a process linguists call "iotacism." Basically, a bunch of different vowels and diphthongs—like eta ($\eta$), iota ($\iota$), and upsilon ($\upsilon$)—all eventually decided they wanted to sound like the "ee" in "cheese."

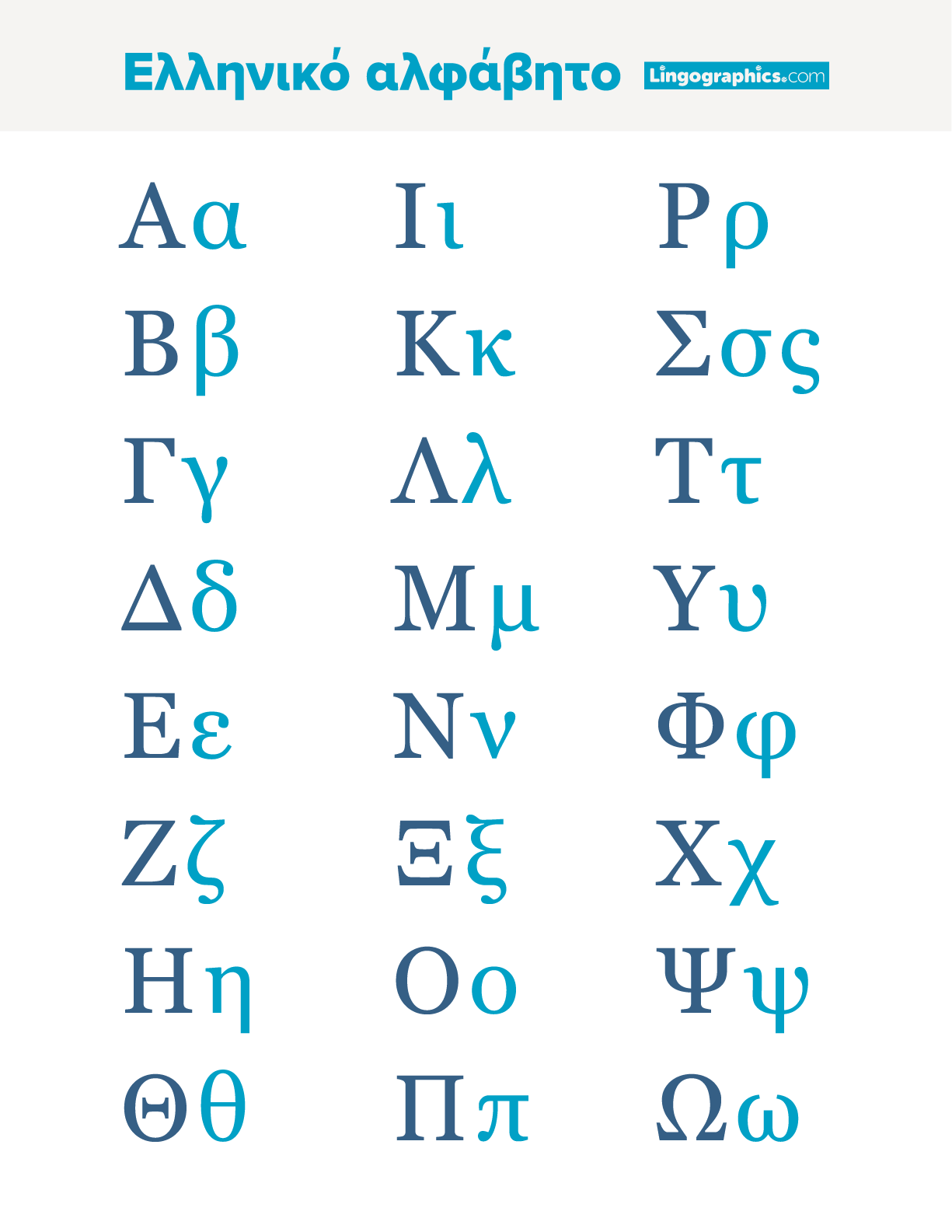

Breaking Down the Letters (and the Noise They Make)

Don't think of these as just static shapes. Think of them as instructions for your mouth.

Alpha (Α α) is the easy one. It’s the "a" in "father." It’s steady. It’s reliable. It’s the starting line.

Then things get weird with Beta (Β β). In the classical era, it was a "b" sound. If you were a sheep in an Ancient Greek comedy, you said "beee, beee" (spelled with beta and eta). But today? It’s a voiced labiodental fricative. That’s a fancy way of saying you put your teeth on your lip and vibrate. "V."

Gamma (Γ γ) is the real troublemaker. Most people think it's a "G" like "goat." Sometimes it is. But often, it's a soft, gargling sound in the back of the throat, like the Spanish "g" in "amigo." And if you put two gammas together ($\gamma\gamma$), they make an "ng" sound like "sing."

Delta (Δ δ) follows the same path. It’s not a hard "D" like "dog" anymore. It’s a "th" sound, specifically the voiced one in "this" or "then." You have to stick your tongue between your teeth. It’s softer than it looks.

Epsilon (Ε ε) and Zeta (Ζ ζ) are relatively straightforward, though Zeta is more of a "z" than the "dz" sound scholars think it was in the days of Plato.

Eta (Η η) is where the drama happens. In Ancient Greek, it was a long "e" like the "e" in "where" (air). Now? It’s just "ee."

Theta (Θ θ) is your classic "th" as in "thought." It’s an unvoiced breath of air.

Iota (Ι ι) is simple. "Ee."

Kappa (Κ κ) is a "k." No surprises here.

Lambda (Λ λ) is "l."

Mu (Μ μ) and Nu (Ν ν) are "m" and "n." They look like a "u" and a "v" sometimes in lowercase, which trips up everyone. Don't let it fool you.

Xi (Ξ ξ) is a "ks" sound. Think "socks." It’s a fun letter to write once you get the hang of the curls.

Omicron (Ο ο) means "little O." It’s a short "o" sound.

Pi (Π π) is "p." You know this from math. You probably didn't know it was a letter first.

Rho (Ρ ρ) looks like a "P" but it’s an "R." And in Greek, you gotta flick that tongue. It’s a slight trill.

Sigma (Σ σ/ς) is "s." It has two lowercase forms. If it’s at the end of a word, it’s $\varsigma$. If it’s anywhere else, it’s $\sigma$. Why? Because Greek likes to keep you on your toes.

Tau (Τ τ) is "t."

Upsilon (Υ υ) is another "ee" sound now, but it used to be like the French "u" or German "ü."

🔗 Read more: Baucke Funeral Services Holyoke Obituaries: Why They Still Matter

Phi (Φ φ) isn't a "p" followed by an "h" breath anymore. It’s just "f."

Chi (Χ χ) is that raspy "ch" sound you hear in "Bach" or "Loch Ness." It’s not a "k." If you say "chai" like the tea, you’re closer than saying it like "kite."

Psi (Ψ ψ) is "ps" like "maps."

Omega (Ω ω) is the "big O." It used to be a long "o" like "boat," but now it sounds exactly like Omicron.

The Mystery of Diphthongs

A diphthong is just two vowels hanging out together to make a new sound. Greek loves these. But modern Greek has simplified them so much that it makes spelling a nightmare for Greek schoolchildren.

Take "Alpha Iota" ($\alpha\iota$). It used to sound like "eye." Now it sounds like "eh" (the "e" in "pet").

"Omicron Iota" ($\omicron\iota$) and "Epsilon Iota" ($\epsilon\iota$)? They both just sound like "ee" now.

This means you can have five or six different ways to spell the "ee" sound in a single sentence. It’s the ultimate spelling bee challenge.

Why We Still Use It (And Why You Should Care)

The Greek alphabet and sounds are the foundation of scientific nomenclature. When a doctor talks about "haematology," they’re using the Greek word for blood, haima. The "ai" in haima is that diphthong we just talked about.

In astronomy, stars are ranked by their brightness using Greek letters. Alpha Centauri is the brightest in the Centaurus constellation. In psychology, we talk about "alpha" personalities or "theta" brain waves.

But beyond the technical stuff, understanding these sounds helps you decode the English language. About 12% of English vocabulary is Greek-derived. If you know that "poly" means many and "glotta" means tongue/language, you suddenly realize a polyglot isn't some weird creature—it's just someone who speaks a lot of languages.

Real-World Examples of Confusion

One of the biggest pitfalls is the letter Chi (Χ). In English, we often turn it into a hard "K." Think of "Christmas" (from Christos) or "Character." But in the original Greek alphabet and sounds, that "ch" was a distinct, breathy friction.

Another one is Phi (Φ). We see it in "Philosophy." The Greeks didn't always say "f-ilosophy." In the earliest stages, it was an aspirated "p"—like the "p" in "pot" but with a much bigger puff of air. Over centuries, that puff of air turned into the continuous "f" sound we use today.

Common Misconceptions

People think the Greek alphabet is "hard." It's not. It has 24 letters. English has 26. Most of the letters actually look and sound like ours because ours came from theirs (via the Romans).

The real difficulty isn't the letters; it's the breathings and accents. If you look at an old Greek text, you'll see little marks over the vowels. Some were "rough breathings," which meant you added an "h" sound at the start of the word. Others were pitch accents. Ancient Greek was a tonal language, kind of like Chinese. You didn't just stress a syllable; you changed the musical pitch of your voice.

By the 3rd or 4th century CE, the pitch accent turned into a stress accent, which is what we use today. The "musical" quality of the language mostly died out, replaced by the rhythmic beat of modern speech.

Actionable Insights for Learning

If you actually want to master the Greek alphabet and sounds, don't just memorize a list. That’s boring and it won't stick.

- Write your name. Use the closest Greek equivalents. If your name is "David," you’d use Delta, Alpha, Beta, Iota, Delta ($\Delta\alpha\beta\iota\delta$). It’s the fastest way to build muscle memory.

- Read signs. If you ever visit Greece, don't just look at the English translations. Try to sound out the Greek characters on street signs. "STOPS" is $\Sigma T O \Pi$. You already know those letters.

- Use Mnemonics. Theta is a circle with a "th"read through it. Phi is a circle with a "f"lagpole.

- Listen to Modern Greek. Go on YouTube and find a Greek news broadcast. Listen to the "v" sounds of Beta and the "th" sounds of Delta. It will break the habit of using English "B" and "D" sounds.

- Understand the context. Know that Ancient Greek pronunciation is a reconstruction. Nobody alive truly knows exactly how Socrates sounded. We have very good guesses based on how they wrote jokes and how they transcribed foreign words, but there's always a margin of error.

The Greek alphabet and sounds offer a window into how humans organize thought. Every time you use a letter, you're using a piece of technology that was refined over thousands of years by some of the most inquisitive minds in history. It’s not just a dead script. It’s a bridge between the ancient world and the digital one we live in now.

Start by learning five letters today. Just five. Lambda, Mu, Nu, Xi, Omicron. By the time you get to Omega, the world of science, history, and etymology will look completely different to you. There's no "ultimate" way to learn it, just the way that starts with you actually looking at the letters and making the noise.

Start with Alpha. The rest follows naturally.