You think you know the Sierra Nevada until you actually look at a topographical map of the sierra mountains. Most people just see a big, jagged spine running down California. But honestly? It's a 400-mile-long labyrinth. If you’re planning a trip to Yosemite, Tahoe, or the Whitney Portal, looking at a flat screen doesn't give you the full story. It’s basically a massive block of the Earth's crust that tilted up like a trapdoor. One side—the west—is a long, slow grind through foothills and oak trees. The other side—the east—is a brutal, vertical drop into the desert.

Maps lie. Well, they don't exactly lie, but they simplify things so much that you might miss the "Rain Shadow" effect or why a 10-mile hike in the High Sierra feels like 30 miles in the Appalachians.

The Big Picture: Understanding the Range’s Anatomy

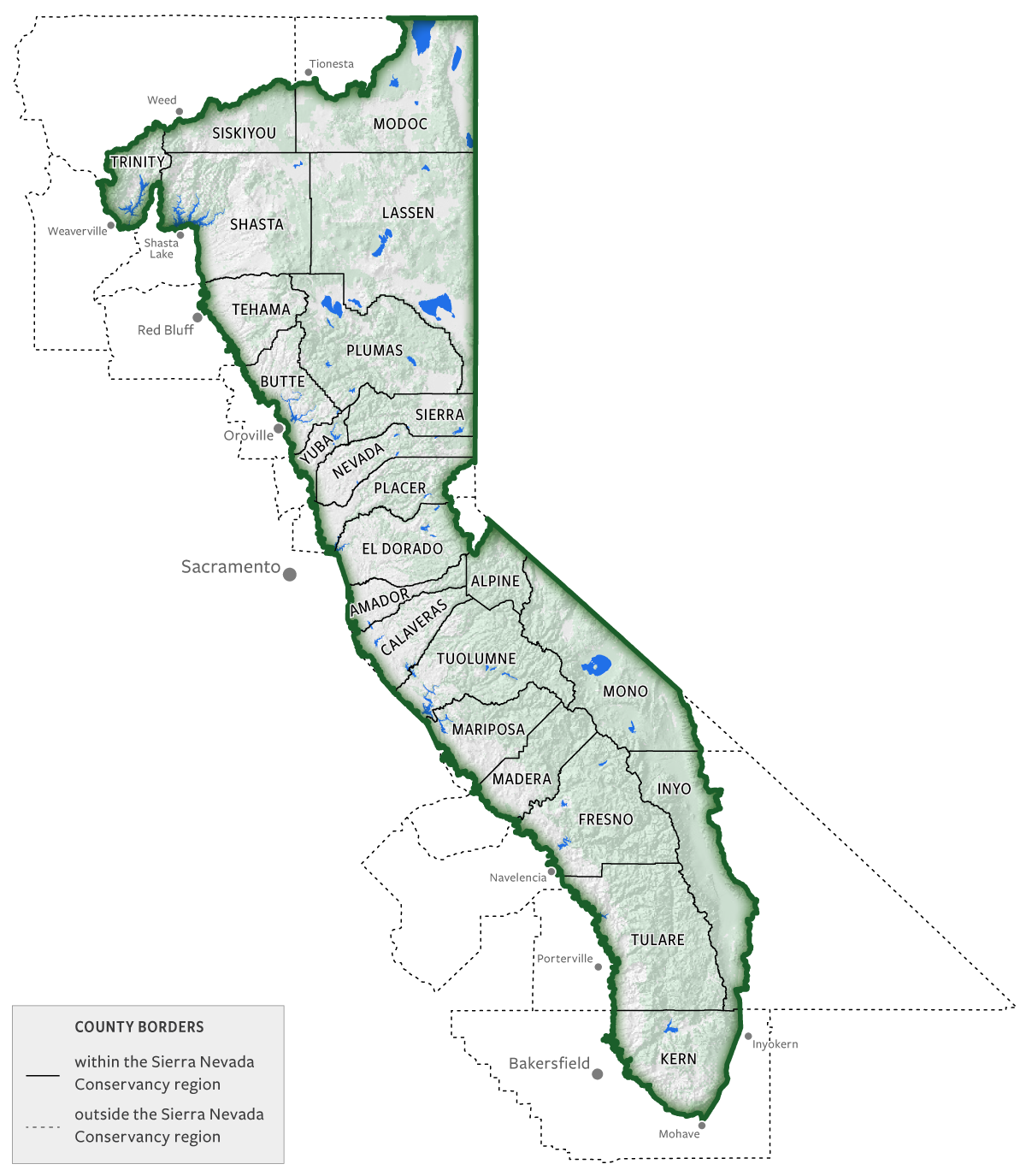

When you pull up a map of the sierra mountains, the first thing you notice is the sheer scale. We’re talking about a range that’s larger than the French, Swiss, and Italian Alps combined. It’s huge. Geologists like the late Mary Hill, who wrote extensively on the region’s geology, often pointed out that the range is essentially one giant piece of granite.

Look at the northern section near Lake Tahoe. It’s lower, greener, and broken up by volcanic activity. Then, move your eyes south. By the time you hit the Palisades and Mount Whitney, the "High Sierra" takes over. This is where the maps get crowded with contour lines. Those lines are so close together they look like solid black ink because the elevation changes are so violent.

The Western Slope is where the big rivers live. The Feather, the American, the Tuolumne, the Kings. These carved the deep canyons you see on your map. If you’re driving up from the Central Valley, you’re crossing these deep gashes. It’s why driving from North to South through the mountains is almost impossible; most of the major roads (Highway 50, I-80, Highway 120) run East-West.

Why the East Side is Different

The Eastern Sierra is a different beast entirely. On a map, look at Highway 395. It hugs the base of the mountains. To your west, the peaks rise 7,000 to 10,000 feet straight up from the valley floor. There are no foothills here. It’s just flat desert, then BOOM—granite wall. This is because of the Sierra Nevada Fault Zone. The ground literally dropped away while the mountains pushed up.

If you're backpacking here, your map is your lifeline. Water is scarce on the eastern side compared to the lush western meadows. You’ll see "blue lines" on the map, but in August, many of those are bone-dry.

💡 You might also like: Redondo Beach California Directions: How to Actually Get There Without Losing Your Mind

National Parks and the Great Green Blobs

You probably recognize the big green patches on any map of the sierra mountains: Yosemite, Sequoia, and Kings Canyon. These are the crown jewels, but they only represent a fraction of the land. Surrounding them is a patchwork of National Forest land—Tahoe, Eldorado, Stanislaus, Sierra, and Inyo National Forests.

- Yosemite: The map shows a valley, but it’s really a glacial scar.

- Sequoia/Kings Canyon: Here, the map shows the "High Sierra Trail," which is one of the few ways to cross the range without a car.

- Ansel Adams Wilderness: This is the photographer's dream, sandwiched between Yosemite and Mammoth Lakes.

The John Muir Trail (JMT) is the "highway" for hikers. It stretches about 211 miles from Yosemite Valley to the summit of Mount Whitney. When you study the JMT on a map, pay attention to the passes. Muir Pass, Mather Pass, Glen Pass. These are the high points where the trail crosses over the ridges. Even in July, a good topographical map will show you that these areas might still be under ten feet of snow.

Don't Trust Your GPS Blindly

Here is a piece of advice from someone who has spent way too much time staring at paper maps in the dark: Google Maps is dangerous in the Sierra. Every year, people follow "shortcuts" suggested by their phones and end up on 4WD logging roads that haven't been maintained since the 1970s.

You need to understand the difference between a "Forest Service Road" and a paved highway. On a real USFS map, these are coded. Solid lines are usually paved. Dashed lines? You better have high clearance and a spare tire. Or two.

The Mystery of the "Closed" Passes

Look at Tioga Pass (Highway 120) or Sonora Pass (Highway 108). During the winter, these roads literally disappear from digital navigation because they are closed under 20-40 feet of snow. If you are looking at a map of the sierra mountains in January and trying to get from Bishop to Fresno, the map says it's only 80 miles as the crow flies. In reality, you have to drive 300 miles north to Tahoe or 300 miles south to Bakersfield just to get around the wall.

The Sierra is an absolute barrier for half the year.

📖 Related: Red Hook Hudson Valley: Why People Are Actually Moving Here (And What They Miss)

Reading the Terrain: Glaciers and Granite

What makes the Sierra map so distinct is the evidence of the Last Glacial Maximum. Thousands of years ago, massive ice sheets ground down the granite. This created "cirques"—those bowl-shaped valleys that hold high-altitude lakes. On your map, these look like tiny blue circles surrounded by steep U-shaped ridges.

Take a look at the Minarets near Mammoth. They look like jagged teeth. That’s because they were so high and sharp that the glaciers couldn't grind them down. They stood above the ice.

Then you have the "domes." Half Dome, Lembert Dome, Sentinel Dome. These are exfoliation domes. On a map, they appear as almost perfect circles of contour lines. They are unique to the Sierra because of the specific way this granite cools and cracks.

The Snowpack Factor

You can't talk about a map of the sierra mountains without talking about the "Range of Light," as John Muir called it. But it’s also the "Range of Snow." The Sierra acts as a giant sponge for California’s water.

When you look at a map of the watersheds, you see how every drop of rain or snow eventually flows into the San Joaquin or Sacramento rivers. This water feeds the entire Central Valley, which grows a huge chunk of the world’s produce. So, that map isn't just for hikers; it’s a map of California's life support system.

Planning Your Route: Expert Nuance

If you're actually going to use a map of the sierra mountains for a trip, you need to look at the "aspect" of the slopes.

👉 See also: Physical Features of the Middle East Map: Why They Define Everything

- North-facing slopes: These stay snowy way longer. A map might show a trail crossing a north slope at 10,000 feet. Even if the south side is dry, that north side could be an icy slide of death in June.

- Drainages: In a heavy rain year, small creeks on the map become impassable rivers. Evolution Creek is a famous example on the JMT—it looks small on paper, but hikers have drowned trying to cross it during the spring melt.

- Treeline: In the Sierra, the treeline is usually around 10,000 feet. If your map shows you camping at 11,000 feet, don't expect to find firewood. It’s all rock and sky up there.

The "Dead Zones"

There are parts of the map where there are simply no roads and no easy access. The "Great Western Divide" is one of those places. It’s a sub-range within the Sierra that keeps the Kaweah River separate from the Kern. It is incredibly remote. If you want to see what California looked like 500 years ago, that’s where you look on the map.

Moving Beyond the Paper

Maps are tools, but the Sierra is a living thing. The topography is constantly changing due to rockfalls and forest fires. If you’re using an old map from the 90s, the "green" forested areas might now be burn scars.

Always cross-reference your map of the sierra mountains with current Forest Service "Burn Area Emergency Response" (BAER) maps. This tells you where trails might be washed out or where "widow-makers" (standing dead trees) are a risk.

Practical Steps for Your Next Trip

- Download Offline Maps: Don't rely on cell service. It doesn't exist once you're five miles past the trailhead. Use apps like Gaia GPS or OnX, but download the layers before you leave the house.

- Get the Tom Harrison Maps: Ask any Sierra expert—Tom Harrison maps are the gold standard for hikers. They are waterproof, tear-resistant, and have the most accurate trail mileage.

- Check the Inyo National Forest Website: They have the most up-to-date info on the Eastern Sierra, which is the most volatile part of the range.

- Study the "Passes": If you're driving, memorize the names of the passes (Donner, Echo, Carson, Ebbetts, Sonora, Tioga). If one is closed, they all might be.

- Respect the "PCT": The Pacific Crest Trail runs the length of the range. Even if you aren't hiking it, it's a great reference point on any map to orient yourself.

The Sierra Nevada isn't just a destination; it's a massive, complex geological event that's still happening. Whether you're looking at a map of the sierra mountains to find a campsite or just to understand why California's weather is so weird, remember that the map is just a two-dimensional ghost of the real thing. Go see the granite for yourself. Just make sure you know which way is North before the sun goes down behind the peaks.

The best way to start is to pick one specific drainage—like the Middle Fork of the Kings River—and trace it from its headwaters at the crest all the way down to the valley. You'll see the history of the world written in those contour lines.