You look at a standard blue-and-green globe and it's mostly empty space. Water everywhere. But if you zoom in on the specific spots where coral reefs on a map actually exist, you realize they occupy less than one percent of the ocean floor. That's it. A tiny fraction of the planet holding roughly a quarter of all marine life. It's honestly a bit overwhelming when you think about the density of it.

I’ve spent a lot of time looking at bathymetric charts and satellite feeds. Most people think of the Great Barrier Reef immediately, which makes sense because it's massive. But there’s a whole world of "hidden" reefs that don't get the tourist brochures. Finding them requires understanding that coral isn't just a decoration; it's a geological force that literally builds islands.

Why Coral Reefs on a Map Look Different Than You Think

When you’re browsing a digital map, you might see a solid block of color indicating a reef. In reality, it’s a chaotic, three-dimensional sprawl.

Most maps prioritize the "Coral Triangle." This is the global epicenter of marine biodiversity, a rough triangle spanning Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Papua New Guinea, Timor-Leste, and the Solomon Islands. If you want to see the highest concentration of species, that's your bullseye. Scientists like Dr. Charlie Veron, often called the "Godfather of Coral," have documented over 600 species of reef-building corals in this region alone. That is staggering.

But maps are tricky. A static map doesn't show the depth. Most reef-building corals—the ones we call "zooxanthellate"—need sunlight. This means they are almost always found in the photic zone, generally shallower than 50 meters. If you see coral reefs on a map located far out in the middle of the Pacific, you're usually looking at an atoll. This is a ring-shaped reef that originally grew around a volcanic island which has since sunk or eroded away.

It's a weird kind of ghost story written in calcium carbonate.

The Great Barrier Reef is just the start

Everyone knows the Australian powerhouse. It stretches over 2,300 kilometers. You can see it from space. But have you ever looked at the Red Sea on a map?

The Red Sea contains some of the most resilient corals on Earth. While the Great Barrier Reef has suffered through massive bleaching events in 2016, 2017, and 2020, the corals in the northern Red Sea, particularly around the Gulf of Aqaba, seem oddly immune to rising temperatures. Researchers at the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL) found that these corals have a high thermal tolerance. They are basically the "super-corals" of the future. On a map, this area looks like a thin ribbon of life hugging a desert coastline. The contrast is beautiful.

✨ Don't miss: Anderson California Explained: Why This Shasta County Hub is More Than a Pit Stop

How to Actually Use Map Data for Conservation

We aren't just using paper maps anymore. Technology has fundamentally changed how we track these ecosystems. The Allen Coral Atlas is probably the most significant tool we have right now. It uses high-resolution satellite imagery and machine learning to map the world's reefs in unprecedented detail.

Before this, we were basically guessing.

We had "representative" maps that were often decades old. Now, we can see changes in real-time. This is vital because coral reefs on a map are moving. Well, they aren't "walking," but their viable habitats are shifting. As the oceans warm, some species are attempting to migrate toward the poles. It's a slow-motion escape.

But corals can't just pick up and move. They need the right substrate. They need the right light. They need the right chemistry.

The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef

Often overlooked in favor of its Australian cousin, the Mesoamerican Barrier Reef is the largest in the Western Hemisphere. It touches Mexico, Belize, Guatemala, and Honduras. If you look at this area on a map, you'll see the famous Great Blue Hole in Belize. This is a giant marine sinkhole. From a mapping perspective, it’s a perfect circle of deep blue surrounded by shallow turquoise.

Belize has been a bit of a leader here. They were one of the first countries to ban offshore oil exploration to protect their reef. It's a rare win.

The Misconception of "Deep Water" Reefs

Here is something most people get wrong. When you look at coral reefs on a map, you are usually looking at tropical, shallow-water reefs. But there is a whole other world of cold-water corals.

🔗 Read more: Flights to Chicago O'Hare: What Most People Get Wrong

They don't need sunlight.

They live in the dark, thousands of meters down. There are massive cold-water reef systems off the coast of Norway and in the deep canyons of the Atlantic. These don't show up on your typical "vacation" map. They grow incredibly slowly—sometimes only a few millimeters a year. These are the ancient forests of the sea. They are fragile and often destroyed by bottom trawling before we even know they are there.

The Problem with GPS and Small Reefs

I've talked to divers who spent days trying to find a specific patch reef that was marked on a local chart, only to find nothing. Reefs are dynamic. They grow, they break during storms, and they die.

A map is a snapshot in time.

If you are using a map to navigate, especially in places like the Florida Keys or the Bahamas, you have to be incredibly careful. Grounding a boat on a reef is a death sentence for the coral. It crushes the delicate polyps. It takes decades to recover from a single ship strike. Modern nautical charts are better, but they still struggle to capture the granular detail of a changing reef.

Putting the Pieces Together

So, what are you actually looking for when you search for coral reefs on a map?

Usually, it's one of three things:

💡 You might also like: Something is wrong with my world map: Why the Earth looks so weird on paper

- Fringing Reefs: These are the most common. They grow directly from the shore. No lagoon between the reef and the land.

- Barrier Reefs: These are separated from the shore by a lagoon. Think of them as a protective wall.

- Atolls: Those circular reefs in the open ocean I mentioned earlier.

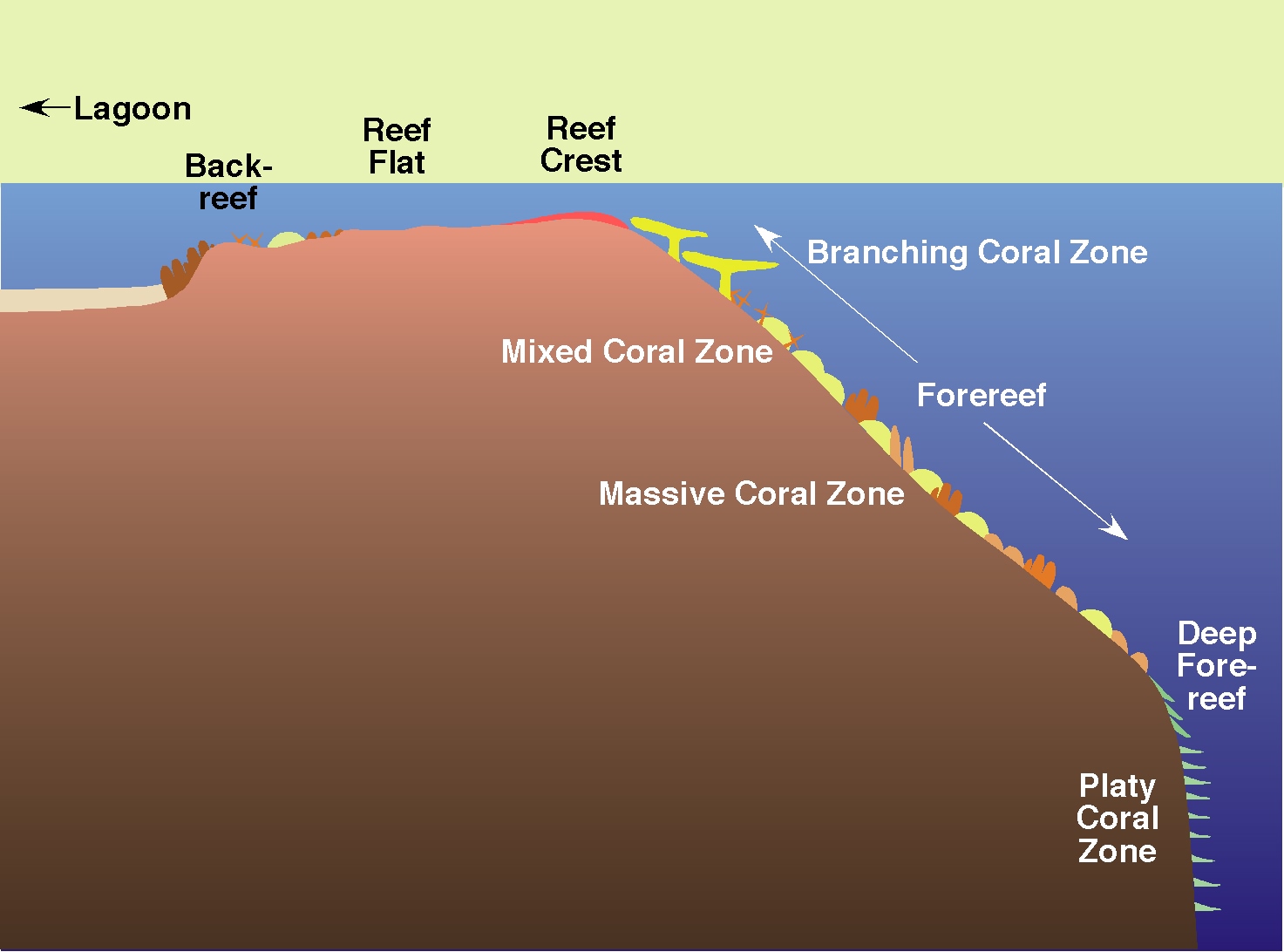

Understanding these structures helps you read the landscape. If you see a lagoon on a map, you know the water will be calm and shallow. If you see the "reef crest" (the part that breaks the waves), you know that's where the most oxygenated water is, and usually where the bigger fish hang out.

Real Talk: The Threat Level

We can't talk about maps without talking about the "red zones." Over 50% of the world's coral has been lost in the last 30 years. When you look at a map of the Caribbean today versus 1970, it’s heartbreaking.

Diseases like Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) are spreading across the maps like a wildfire. It started in Florida in 2014 and has since marched across the Caribbean. We are literally watching the colors fade on our maps.

Taking Action Beyond the Screen

Mapping is the first step toward protection. You can't save what you don't measure.

If you want to do more than just look at a map, there are real things you can do. It's not just about "saving the turtles" (though that's great). It's about systemic change.

- Use the Allen Coral Atlas: Go play with the data. It's free and public. See how reefs in your favorite vacation spots have changed over the last five years.

- Support Marine Protected Areas (MPAs): These are the "national parks" of the ocean. Maps with green borders around reef systems usually indicate these zones. They work. Fish biomass increases, and coral health often stabilizes when fishing pressure is removed.

- Be a Citizen Scientist: If you dive or snorkel, use apps like iNaturalist or Reef Check. You can upload photos and locations that help scientists update the very maps we've been talking about.

- Mind Your Carbon: It sounds cliché, but ocean acidification and warming are the biggest threats. Any reduction in your personal carbon footprint helps buy these ecosystems time to adapt.

- Choose Sustainable Travel: If you visit a reef, don't touch it. Use "reef-safe" sunscreen (avoid oxybenzone and octinoxate). These chemicals are toxic to coral larvae.

The maps of the future depend on what we do right now. We have the technology to see the problem in high definition. Now we just need the collective will to make sure those blue-and-green spots don't turn into gray graveyards.

Exploring coral reefs on a map is a great way to start appreciating the complexity of our planet. Just remember that the map is not the territory. The real territory is a breathing, pulsing, incredibly fragile living organism that needs our attention more than ever.