You’re standing in the garden center, staring at a gorgeous perennial. It’s perfect. You check the tag, and it says "Hardy to Zone 7." You think you're in Zone 7. Or maybe Zone 6b? You try to remember that map you saw three years ago, but honestly, everything feels different now. Winters are weirder. Spring comes in fits and starts. This is exactly why looking up gardening zones by zip has become a seasonal ritual for anyone who doesn't want to throw money away on plants destined to die in the first frost.

It’s about survival.

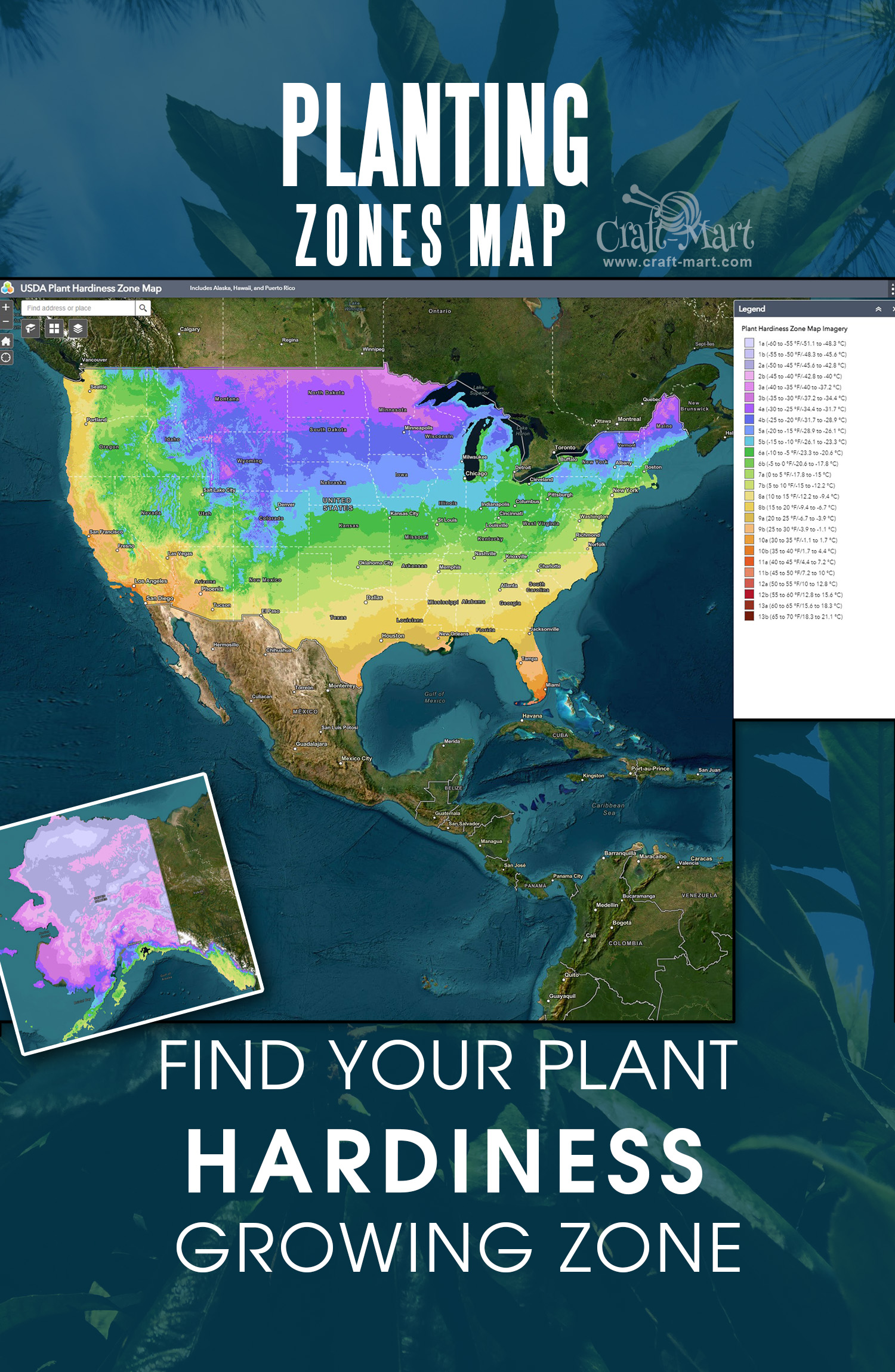

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zone Map is the gold standard, but it’s not just a static picture on the back of a seed packet anymore. In late 2023, the USDA released a massive update to the map, the first in over a decade. About half the country shifted into a new half-zone. That means if you’ve been gardening based on what your grandmother told you, or even what worked in 2010, you might be totally wrong about your own backyard.

The Science Behind the Shift

So, what actually changed? The 2023 map was built using data from 13,332 weather stations. That’s a huge jump from the 7,983 stations used for the 2012 version. When you type in your gardening zones by zip code now, you’re seeing a much more granular, high-resolution image of reality. The map is based on the average annual extreme minimum winter temperature. It’s not about how hot it gets in July. It’s about how cold it gets on that one nightmare night in January when the pipes freeze.

The math is basically 10-degree Fahrenheit increments. Each zone is then split into "a" and "b" halves. For example, Zone 7a is 0 to 5 degrees, while Zone 7b is 5 to 10 degrees. It sounds like a small difference. It isn't. Those five degrees determine whether the fluid inside a plant's cells turns into jagged ice crystals that shred the cell walls or whether the plant just enters a deep, cozy sleep.

Christopher Daly, the director of the PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University—the guys who actually create these maps for the USDA—has pointed out that the warming trend is clear. But it’s not just "global warming" in a broad sense. It’s about more sophisticated mapping. They can now account for things like "urban heat islands" where all that concrete in a city keeps things a few degrees warmer than the surrounding suburbs. They can see how wind moves through a valley. It’s cool, honestly. But it also means your neighbor might technically be in a different zone than you if they’re at the bottom of a hill and you’re at the top.

Why Your Zip Code is Only the Start

Here’s the thing most people get wrong: the zip code is a generalization. A zip code can cover a lot of ground. If you live in a place like Los Angeles or Denver, your zip code might include a sea-level valley and a 2,000-foot ridge. The temperature difference between those two spots is massive.

You’ve got to look at your microclimate.

- South-facing walls: These soak up sun all day and radiate heat at night. You can often grow plants one full zone "warmer" against a brick wall facing south.

- Low spots: Cold air is heavy. It flows downhill like water. If your garden is at the bottom of a slope, you’re in a "frost pocket." You might actually be a half-zone colder than what the zip code search says.

- Wind exposure: Constant wind dries plants out and strips away heat. A Zone 8 plant in a windy Zone 8 spot will die faster than a Zone 7 plant in a sheltered spot.

I knew a guy in Seattle who grew citrus. In Seattle! He had a protected courtyard with stone pavers and a glass overhang. He cheated the system. He ignored the gardening zones by zip results and built his own environment. That’s the level of nuance you need if you want to push the envelope.

The Danger of "Zone Creep"

Just because the map says your area is warmer doesn't mean you should go out and buy a palm tree if you live in Ohio. This is where a lot of folks get burned. The USDA map is an average. It’s the average of the lowest temperatures over a 30-year period.

It does NOT account for the "Polar Vortex" or those "once-in-a-century" freezes that seem to happen every five years now.

💡 You might also like: Department of Motor Vehicles Ruidoso NM: How to Actually Get In and Out Fast

In 2021, Texas had a catastrophic freeze. People who had been planting based on their Zone 8 or 9 designations saw decades-old landscapes wiped out in forty-eight hours. The plants were rated for the average, but they weren't rated for the extreme. If you’re planting a "legacy" tree—something you want to be there for fifty years—you should actually plant for one zone colder than your zip code suggests. It’s insurance. If you’re just planting zinnias or tomatoes, who cares? Those are annuals. They’re gonna die when it gets cold anyway. But for the big stuff? Be conservative.

How to Actually Use the Data

When you find your zone, use it as a filter, not a rule. Most online nurseries now let you filter by zone. Use it. But also look at "Days to Maturity" and "Heat Sensitivity."

Because here is the dirty secret: The USDA map ignores heat.

If you live in the American Southeast, the cold isn't your biggest enemy. It’s the humidity and the 95-degree nights. A plant might be hardy to Zone 5 (meaning it survives the cold), but it might "melt" in a Georgia summer. For that, you need the American Horticultural Society (AHS) Heat Zone Map. It’s less famous than the USDA one, but if you're in the Sun Belt, it’s arguably more important. It measures how many days per year the temperature tops 86 degrees. That’s the point where many plants start to experience physiological stress.

Real-World Examples of Zone Shifts

Let's look at some specifics. Take Minneapolis. It’s legendary for being a frozen tundra. For a long time, it was solidly Zone 4a. Now? Much of the metro area has ticked into 4b or even 5a. That’s a big deal. It opens the door for certain varieties of apples or flowering shrubs that previously would have been a "maybe next year" gamble.

Or look at the Northeast. Places in New York and Connecticut that were firmly Zone 6 are seeing Zone 7 creeping up the coastline. Gardeners are starting to experiment with Crape Myrtles and even certain types of Camellias that used to be strictly Southern staples. It’s exciting, but it’s also a little bit scary. It’s a visual representation of how fast the environment is shifting.

Common Misconceptions to Toss Out

People often think the gardening zones by zip tell you when to plant your vegetables. They don't.

That is a completely different metric called the "Frost Date." Your hardiness zone tells you if a plant will survive the winter. Your frost date tells you when it’s safe to put your tomatoes in the ground without them turning into black mush by morning. You can be in Zone 8 and still have a late frost in April that kills your seedlings. Always check your local university extension office for frost dates. They are the real heroes of local gardening.

✨ Don't miss: Why Men's White Boxer Underwear Still Beats Everything Else in Your Drawer

Another myth? That "native plants" don't care about zones. Even native plants have limits. A plant native to the southern part of a state might struggle in the northern part if the zone is different. Always check the provenance.

Actionable Steps for Your Garden

Don't just look at the map and walk away. Here is how you actually apply this knowledge to your dirt.

First, get the specific data. Go to the USDA website and use their interactive map. Zoom in all the way to your street. Don't just stop at the zip code level. See if you're on a boundary line. If you see your house sits right on the edge of Zone 6b and 7a, act like you're in 6b.

Second, audit your yard. Walk out there in the morning. Where does the frost linger the longest? That’s your coldest spot. Where does the snow melt first? That’s your warmest spot. Label these in your head. Put your delicate, "borderline" plants in the warm spots and your tough-as-nails shrubs in the cold spots.

Third, keep a garden journal. This sounds tedious, but it’s the only way to beat the "average" data. Record the lowest temperature your backyard thermometer hits every winter. After three years, you'll have a better "zone" map than any government agency could give you because it’s your data.

Fourth, look for the "over-winter" success stories. Look at what your neighbors are growing. If you see a neighbor with a thriving Japanese Maple that shouldn't survive in your "official" zone, ask them about it. They might have a windbreak or a soil trick you can copy.

Fifth, prepare for the outliers. If you decide to plant something that’s a bit of a stretch for your gardening zones by zip, have a plan. Keep some frost blankets or even old burlap sacks in the garage. When the weather forecast predicts a "black swan" cold event, you’ll be the only one on the block whose garden doesn't look like a wasteland the next week.

🔗 Read more: Mid Century Modern Wainscoting: Why Most People Get the Look Wrong

The map is a guide, not a cage. It’s there to give you the best chance of success, but the real magic happens when you understand the specific quirks of your own patch of earth. Know your zone, but know your yard better. That’s the difference between a person who buys plants and a person who actually grows them.

Next Steps for Success

- Download the latest USDA high-resolution map for your specific state to see the color-coded transitions.

- Identify your last spring frost date by contacting a local university extension; this is different from your hardiness zone.

- Install a basic outdoor thermometer with a "min/max" memory function to track your garden's actual extreme lows this coming winter.

- Group your plants by "thirst" and "toughness" rather than just aesthetics to ensure they survive the specific microclimates in your yard.