You’ve seen it a thousand times. You open a classroom atlas or scroll through Google Maps, and there it is—or isn't. Finding the north pole on world map is actually a lot more frustrating than it sounds because, honestly, most maps are lying to you.

The top of the world is a mess of shifting ice and political bickering. Unlike Antarctica, which is a solid continent covered in ice, the North Pole is just ocean. Deep, dark, freezing water. When you look at a standard Mercator projection, that familiar rectangular map on every office wall, the North Pole doesn't even really exist as a point. It’s stretched into a long, distorted line that makes Greenland look as big as Africa. It isn't. Africa is actually fourteen times larger.

Maps are flat. The Earth is round. You can't flatten a orange peel without tearing it, and that’s exactly what happens to the Arctic.

Where is the North Pole on World Map exactly?

If you’re looking at a standard map, you’re looking at $90^\circ\text{N}$ latitude. But there’s a catch. Or rather, two catches. There is the Geographic North Pole and the Magnetic North Pole.

The Geographic North is the "True North." This is the fixed point where all those longitudinal lines meet at the top of the globe. It's the axis of the Earth's rotation. If you stood there, every single direction you looked would be South. Every one.

Then there’s the Magnetic North Pole. This is where your compass points. It’s not a fixed spot. It moves. In fact, it’s currently skedaddling away from Canada toward Siberia at a rate of about 34 miles per year. This makes life very difficult for cartographers and pilots. When you see the north pole on world map today, you’re usually looking at the geographic version, but if you’re actually trying to navigate there, you need to know the "declination"—the gap between where the map says North is and where your needle is actually swinging.

🔗 Read more: New York 7 Day Weather Forecast: What Most People Get Wrong

The Mercator Problem

Why does the Arctic look so huge on some maps? Gerardus Mercator designed his map in 1569 for sailors. He needed a way to draw straight lines for navigation. To do that, he had to stretch the areas near the poles.

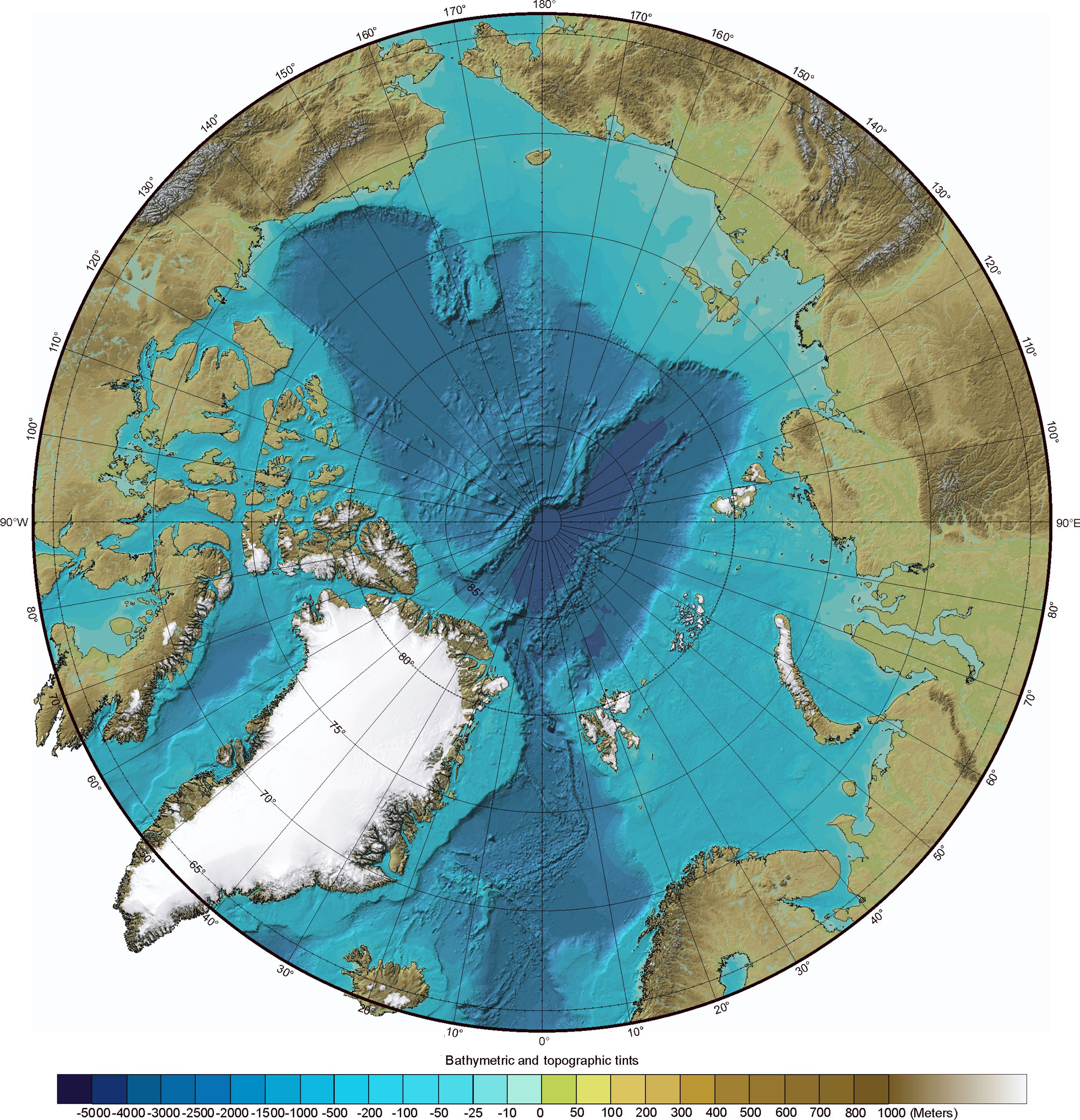

The result? The closer you get to the North Pole, the more "inflated" the landmasses look. This is why the Arctic Ocean often looks like a giant, gaping white void at the top of a map. If you want a more accurate view, you have to look at a "Polar Projection" or an azimuthal equidistant map. These look like a circle with the North Pole right in the center. It’s the view you see on the United Nations flag.

It’s a much more honest way to look at the world. You see how close Russia, Canada, and the United States actually are. In a standard view, they feel worlds apart. In a polar view, they’re neighbors huddled around a cold pond.

The Scramble for the Seabed

Nobody owns the North Pole. At least, not yet.

International law, specifically the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), says that no country owns the Geographic North Pole or the Arctic Ocean region surrounding it. Instead, the five surrounding countries—Russia, Canada, Norway, Denmark (via Greenland), and the United States—are limited to an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles from their coasts.

But things are getting weird.

✨ Don't miss: Why Being on the Beach Alone is Actually the Best Way to Travel

Russia literally dropped a titanium flag on the seabed at the North Pole in 2007 using a submersible. They claim the Lomonosov Ridge, an underwater mountain range, is an extension of their continental shelf. If they prove that, they could claim rights to a massive chunk of the Arctic. Denmark and Canada have made similar claims. Why? Money. And oil. And shipping lanes. As the ice melts, the "Northwest Passage" and the "Northern Sea Route" are becoming viable shortcuts for global trade.

When you look at the north pole on world map in a decade, the borders might look very different than they do now.

Realities of the Arctic Environment

Forget what you saw in cartoons. There are no penguins at the North Pole. Those are in the South.

The North Pole is inhabited by polar bears, but even they don't hang out right at $90^\circ\text{N}$ very often because there isn't much to eat. The "ground" is a floating sheet of sea ice that’s usually 6 to 10 feet thick. Underneath that? About 13,000 feet of water.

- Temperature: Summer averages around 32°F (0°C). Winter drops to -40°F.

- Daylight: The sun rises once a year and sets once a year. Six months of light, six months of dark.

- Life: You’ll find Arctic foxes, some migratory birds, and tiny crustaceans under the ice.

The ice is shrinking. Data from the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) shows that Arctic sea ice extent has declined significantly every decade since satellite record-keeping began in 1979. We are looking at "ice-free" summers in the relatively near future. This doesn't mean the water disappears, but it means the white cap you see on the north pole on world map will be blue during the summer months.

👉 See also: Finding Your Way: The Indianapolis Map of US Geography and Why It Matters

Practical Steps for Understanding the Arctic

If you’re trying to get a handle on the top of the world for a project, or just because you’re a map nerd, don't rely on a single source.

- Use a Globe: Seriously. It’s the only way to see the spatial relationship between the Arctic nations without the Mercator distortion.

- Check the Magnetic North: If you're using a physical compass, use a tool like the NOAA Magnetic Field Calculator. The North Pole on your map isn't where your compass is pointing.

- Look at Bathymetric Maps: These show what’s under the water. The ridges and basins of the Arctic Ocean are where the real political and geological battles are happening.

- Compare Projections: Open a web browser and compare a Mercator map to a Gall-Peters or a Robinson projection. Notice how the "size" of the North Pole changes.

The Arctic isn't just a point on a map. It’s a shifting, melting, politically charged ocean that is becoming the most important geopolitical theater of the 21st century. Knowing how to read the north pole on world map is about more than just finding Santa—it's about seeing how the world is changing in real time.

Stop looking at the top of the map as a finished edge. It’s a center point. Once you rotate your perspective and look down at the world from the top, the proximity of global powers and the fragility of the ice becomes incredibly obvious. Use tools like Google Earth to tilt the camera directly over the pole. It changes how you see everything._