You’ve been staring at 42-Across for twenty minutes. The coffee is cold. The cursor is blinking on that digital grid like a taunt, and honestly, you're about two seconds away from throwing your phone across the room. We’ve all been there. Searching for a New York Times crossword solution isn't just about admitting defeat; it’s about maintaining your sanity when Will Shortz (or the current editorial team) decides that a 1920s jazz singer is "common knowledge." It isn't. Not for most of us.

Crosswords are weird. They are this specific blend of trivia, linguistics, and straight-up psychological warfare. When you hunt for a solution, you aren't just looking for a word; you're looking for the logic behind the grid.

Why the New York Times crossword solution is harder than it looks

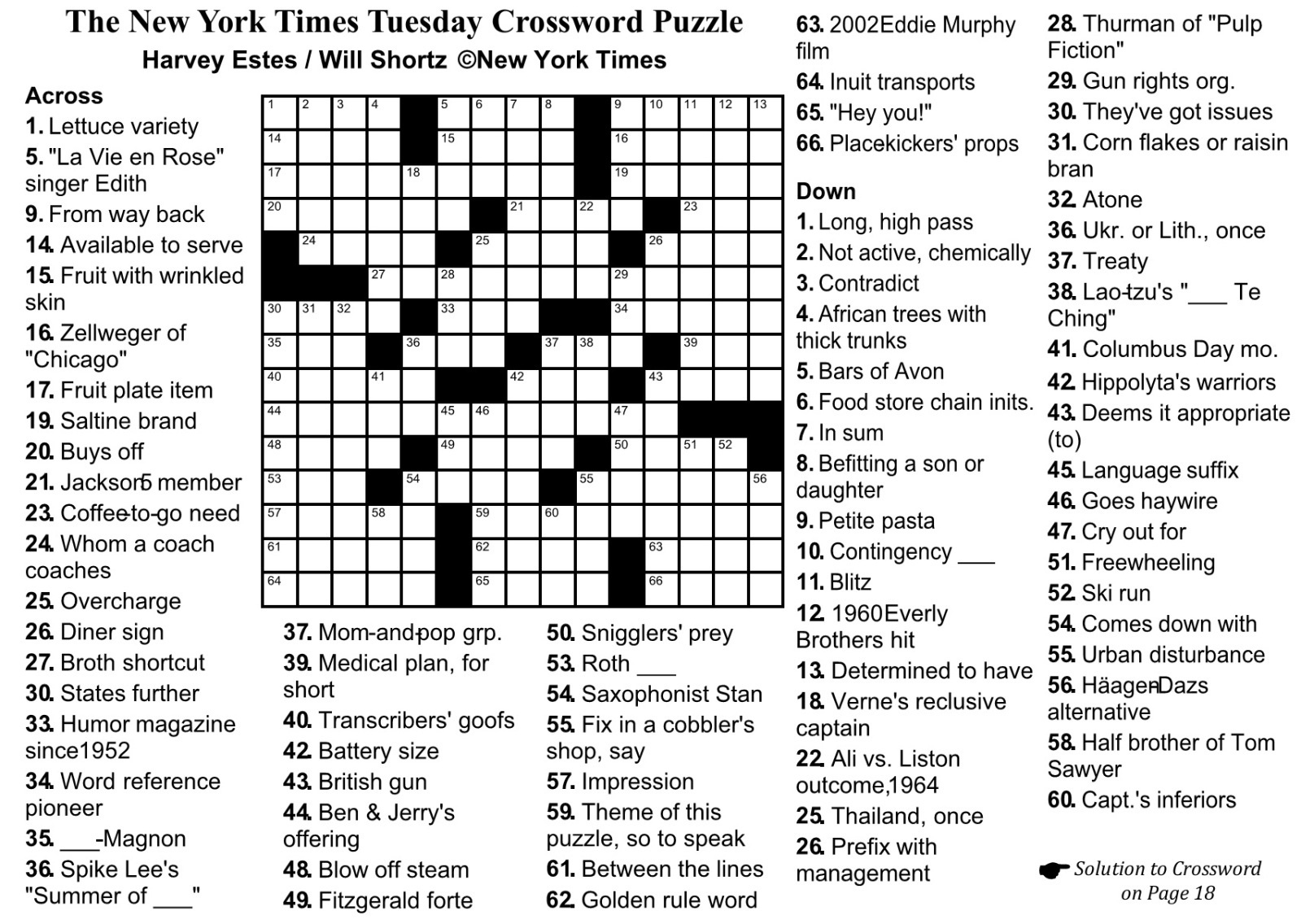

The NYT crossword follows a very specific difficulty curve. Mondays are breezy. You feel like a genius. By Thursday, the "rebus" squares show up—those annoying little boxes where you have to cram an entire word like "CAT" or "HEART" into a single square. If you don't know that's a possibility, you'll never find the New York Times crossword solution because the grid literally won't fit the letters.

Fridays and Saturdays? Forget about it. Those are "themeless" days. They rely on "late-week" cluing. That means the clue isn't a definition; it’s a riddle. If the clue is "Barker on a set," it isn't a dog. It’s a director. Or maybe a carnival worker. This kind of misdirection is why people flock to sites like Wordplay (the official NYT column) or Rex Parker Does the NYT Crossword Puzzle. People need to know if they're actually crazy or if the puzzle is just objectively mean.

The grid is a living thing. It changes. It adapts to pop culture. One day you're looking for a 17th-century poet, and the next, you're trying to remember the name of a viral TikTok dance. It’s exhausting.

The psychology of the "Aha!" moment

There is a genuine dopamine hit when you finally crack a clue. Neuroscientists often talk about "insight problem solving." It's that moment where your brain reorganizes information. You see the clue "Lead for a pencil?" and you think of graphite. Wrong. You think of the metal lead. Wrong. Then, suddenly, it hits you. The answer is "EEN." As in "pencilee-n." It’s a "lead" in the sense of a suffix.

That's the sick joy of it.

But when that moment doesn't come, the frustration is real. Research into cognitive puzzles suggests that hitting a "mental wall" can actually impede your ability to think laterally. This is why walking away—or, let's be real, looking up a New York Times crossword solution—can actually help you learn. You aren't "cheating" so much as you are expanding your internal database of "crosswordese."

Common culprits in your quest for the New York Times crossword solution

If you’re stuck, it’s probably one of the "usual suspects." Crossword constructors love short words with lots of vowels. If you see a three-letter bird, it’s an ANI or an ERN. A three-letter beverage? Probably ADE.

✨ Don't miss: Ranni's Rise Elden Ring: Why You Can’t Get In and What to Do Next

Here are the words that appear way more often in the NYT than they do in actual human conversation:

- ETUI: A small ornamental case for needles. Nobody has used this word in a sentence since 1850.

- ALEE: On the side away from the wind. Sailors use it; crossword fans live by it.

- ERATO: The Muse of lyric poetry. All the Muses are fair game, but Erato is a favorite because of those vowels.

- OLIO: A miscellaneous collection or a spiced stew.

- ORR: Bobby Orr, the hockey legend. If you see a three-letter hockey name, it’s him.

Understanding this "crosswordese" is half the battle. When you look up a New York Times crossword solution, pay attention to these repeats. You'll start to see patterns. You’ll realize that the constructors aren't always trying to test your knowledge; sometimes they're just trying to fill a corner of the grid where three vowels have to touch two consonants.

The "Theme" is your best friend

Sunday through Thursday, the puzzle has a theme. This is the secret code. If you can figure out the theme, the long answers (the "revealers") become much easier to guess. Usually, the theme is hinted at by a specific clue, often located near the bottom right or in the very center.

Sometimes the theme involves "puns." Other times it’s "vowel progression" where the words follow a pattern like BAT, BET, BIT, BOT, BUT. If you're looking for a New York Times crossword solution on a Wednesday, and things feel "off," check if the answers are doing something weird, like turning a corner or reading backward.

Where to find the New York Times crossword solution safely

Look, there are a million "spoiler" sites out there. Some are better than others.

- Rex Parker: This is the "grumpy uncle" of the crossword world. Michael Sharp, a professor at Binghamton University, writes this blog. He is brutally honest. If a puzzle is bad, he will tear it apart. It’s a great place to see the full grid, but also to read a critique of the "fill."

- XWord Info: This is the data nerd’s paradise. It tracks every single word ever used in the NYT crossword. If you want to know how many times "ALEE" has appeared since 1944, this is where you go.

- Wordplay (The NYT Blog): Deb Amlen and her team provide "hints" rather than straight-up answers first. This is better if you want a nudge rather than a full spoiler. They explain the logic. They tell you why that one clue was particularly tricky.

Using these resources shouldn't feel like a failure. Even the best solvers use them. Crosswords are a collaborative effort between the constructor and the solver. Sometimes, you just need a bridge to get to the other side of the grid.

Does "cheating" ruin the experience?

Honestly? No.

There’s a concept in gaming called "scaffolding." It’s the idea that you provide enough support to keep the player engaged without doing the work for them. If you're stuck on a single square and it’s preventing you from finishing the rest of the puzzle, just look it up. The New York Times crossword solution is a tool. Use it to finish the grid, learn the new word, and move on with your life. You’ll remember it next time.

The "purity" of solving without help is a noble goal, but life is short. If you're stuck on a "Natick"—that’s crossword slang for a spot where two obscure proper nouns cross and you have no way of guessing the shared letter—just find the answer. It’s a flaw in the puzzle design, not a flaw in your brain.

The evolution of the NYT Crossword

The puzzle has changed a lot since Margaret Farrar became the first editor in 1942. Back then, it was very "proper." No slang. No "low-brow" references.

When Will Shortz took over in 1993, he modernized it. He brought in pop culture, brand names, and more playful cluing. Today, under the current editorial team, we see even more diversity in constructors and clues. You’ll find clues about K-Pop stars, "RuPaul’s Drag Race," and modern tech terms. This makes the New York Times crossword solution more dynamic but also harder for people who aren't plugged into every facet of modern culture.

Nuance in cluing: The Question Mark

Always, always look for the question mark at the end of a clue. This is the international symbol for "I am lying to you."

If a clue says "Bread makers?" it’s not bakers. It’s probably "MINTS" (where money, or "bread," is made). If it says "Fast people?" it’s not runners; it’s "ASCETICS" or people who "fast" for religious reasons. That little punctuation mark changes everything. When you see a question mark, stop thinking literally. Think laterally. Think about puns. Think about homophones.

Actionable steps for better solving

If you want to stop relying on looking up the New York Times crossword solution every single morning, you need a strategy. You can't just dive in and expect to finish a Saturday.

- Start with the "Gimmies": Go through all the clues and only fill in the ones you are 100% sure about. Proper names you know, obvious definitions, etc.

- Work the Crosses: Don't try to solve the long across clues first. Solve the short down clues that intersect them. This gives you "anchor letters."

- Guess the Suffixes: Many clues are plurals (ending in S) or past tense (ending in ED). If the clue is plural, put an S in the last box. It works about 90% of the time.

- Take a Break: This sounds like "wellness" advice, but it's actually biological. Your brain continues to work on the puzzle in the background (incubation). When you come back an hour later, the answer often jumps out at you.

- Keep a List: When you look up a New York Times crossword solution and find a word you've never heard of (like "ERNE" for a sea eagle), write it down. You will see it again. Crossword constructors are creatures of habit.

The ultimate goal isn't just to fill the boxes. It's to enjoy the process of unraveling a mystery. Whether you finish it solo or with a little help from a solution site, you're still exercising your brain. You're still learning. And tomorrow, there will be a brand new grid, a brand new theme, and a brand new set of frustrations waiting for you.

Get your pencil (or your stylus) ready. The Monday puzzle is just around the corner, and it’s usually a lot kinder than the one you’re struggling with right now. Use the resources available to you, learn the "crosswordese" vocabulary, and most importantly, don't let a grid of black and white squares ruin your breakfast.

Practical Next Steps for Improving Your Solve Rate:

- Download a Crossword Dictionary: Apps like "Across Lite" or specialized crossword dictionaries can help you search by "pattern" (e.g., L_G_T) rather than just the definition.

- Follow Constructor Blogs: Reading the behind-the-scenes thoughts of people like Brendan Emmett Quigley or Elizabeth Gorski will help you understand "constructor logic."

- Practice on "The Mini": If the full puzzle is too daunting, the NYT "Mini" is a great way to build confidence. It’s 5x5 and usually takes less than two minutes.

- Study "The Vowel Heavy": Memorize 3-letter words with at least two vowels. They are the scaffolding of almost every difficult corner in the grid.