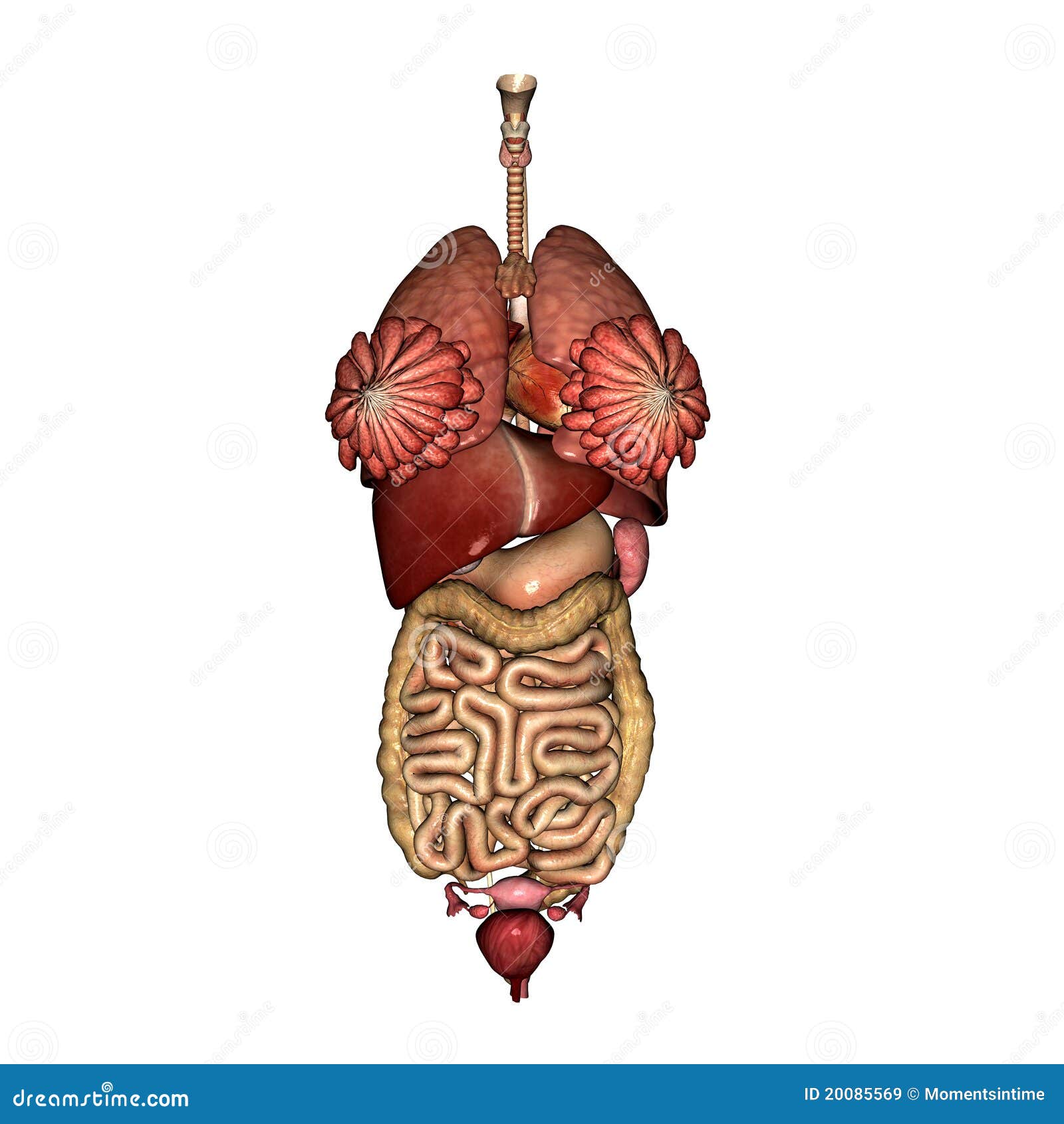

Honestly, it’s a bit wild how much we still don't talk about when it comes to female anatomy with organs. You’d think by 2026, with all the medical tech we have, every person would have a crystal-clear map of their own interior. But nope. Most of us are still walking around with a vague, textbook-diagram idea of what’s happening below the belt.

We need to talk about the reality of it. Not the plastic model in a doctor's office, but the living, shifting, incredibly complex system that actually exists.

The Pelvic Floor is Basically a Trampoline

Think of your pelvic floor as a heavy-duty hammock or a trampoline. It isn't just one thing; it’s a sophisticated layer of muscles and ligaments stretching from your pubic bone to your tailbone. It holds everything up. When we talk about female anatomy with organs, we have to start here because if this "floor" fails, everything else starts to sag. Literally.

Medical professionals like those at the Mayo Clinic or specialized pelvic floor physical therapists will tell you that this area is constantly under pressure. It supports the bladder, the uterus, and the bowel. It’s dynamic. It moves when you breathe. If you’ve ever had a "leaky" moment when sneezing, that’s your pelvic floor struggling to manage intra-abdominal pressure. It’s not just a "post-baby" issue, either. Athletes get it. People with chronic coughs get it. It’s about muscle coordination, not just strength.

The Uterus Isn't Where You Think It Is

Most people point to their belly button when they talk about their uterus. In reality, unless you are pregnant, your uterus is tucked way down deep behind your pubic bone. It’s roughly the size and shape of an upside-down pear.

It’s also incredibly mobile.

The uterus is held in place by several ligaments—the round ligament, the broad ligament, and the uterosacral ligaments—but it’s not bolted down. It tilts. About 75% of women have an "anteverted" uterus, which means it tips forward toward the bladder. The rest? It might be "retroverted," tipping back toward the spine. Neither is "wrong," but a retroverted uterus can sometimes make certain exams or even certain positions during intimacy feel a bit different.

The Layers of the Uterine Wall

It’s a muscular powerhouse. The myometrium is the thick middle layer of smooth muscle. This is what causes those life-altering cramps during a period. It contracts to shed the lining, and eventually, it’s what pushes a human being out of the body. Then there’s the endometrium, the inner lining that responds to hormonal signals every single month. It thickens, it prepares, and if no egg is fertilized, it breaks down.

Ovaries: The Command Centers

If the uterus is the house, the ovaries are the power plants. They are tiny—usually about the size of an almond or a large grape—but they run the show. They don't just sit there. They are actually not directly attached to the fallopian tubes.

This is one of the coolest, weirdest facts about female anatomy with organs: there is a tiny gap between the ovary and the fimbriae (the finger-like ends of the fallopian tubes). When an egg is released during ovulation, those fimbriae have to "sweep" the egg into the tube. It’s like a delicate catch in a game of baseball played at a microscopic level.

💡 You might also like: Big Boobs With Nipples: The Health, Comfort, and Reality Nobody Talks About

- They produce estrogen and progesterone.

- They house your entire lifetime supply of eggs from birth.

- They alternate (usually) which side releases an egg each month.

Ovarian cysts are another thing people get weirdly stressed about. Most of the time, "functional" cysts are just a byproduct of the normal ovulation cycle. They come, they go, and you usually never know they were there. It's when they don't disappear or grow too large that things get tricky.

The Bladder and Bowel Connection

You can't look at a diagram of female anatomy with organs without noticing how cramped it is in there. The bladder sits right in front of the uterus. The rectum sits right behind it.

This is why, when you’re on your period, your digestion might go completely haywire. The prostaglandins—the chemicals that make your uterus contract—don't stay in one lane. They can seep over to the bowel and tell it to contract too. "Period poops" are a scientifically backed phenomenon caused by organ proximity and chemical signaling.

And the bladder? It’s basically a balloon. When it’s full, it pushes on the uterus. When the uterus is enlarged (like during pregnancy or if you have fibroids), it squishes the bladder. It’s a constant territorial dispute in the pelvic cavity.

The Cervix: The Gatekeeper

The cervix is the lower part of the uterus that opens into the vagina. If you’ve ever felt it, it feels sort of like the tip of your nose—firm but slightly give-y. Throughout your cycle, it changes. It moves higher, it gets softer, and the "os" (the opening) changes slightly.

During childbirth, this tiny opening has to dilate to 10 centimeters. That is roughly the diameter of a bagel or a large grapefruit. The fact that human tissue can do that and then return to its original state is, quite frankly, a biological miracle.

📖 Related: That Weird Tickling Crawling Sensation in Ear: Why It Happens and When to Worry

Hidden Anatomy: The Clitoris

For a long time, medical textbooks only showed the tiny external tip of the clitoris. That’s like looking at the tip of an iceberg and saying you’ve seen the whole thing.

The clitoris is actually a massive, wishbone-shaped structure that wraps around the vaginal canal. It has "legs" (crura) and "bulbs" that engorge with blood. It has over 8,000 nerve endings—double the amount in the penis. Its only known purpose in the human body is pleasure. Most of what we understand about the full internal structure of the clitoris only became common knowledge after researchers like Dr. Helen O'Connell used MRI technology in the late 90s to map it out.

Common Misconceptions That Need to Die

We need to stop thinking the vagina is a "void" or a "hole." It’s a potential space. The walls touch each other unless something is inside it. It’s also self-cleaning. The obsession with "feminine washes" and "douches" is one of the biggest scams in modern hygiene. The vaginal microbiome is a delicate balance of Lactobacillus bacteria that keep the pH acidic (around 3.8 to 4.5). If you spray "summer breeze" scents up there, you’re just inviting a yeast infection by killing off the good guys.

Another one: "The Hymen."

It isn't a seal. It isn't a "freshness seal" that gets broken. It’s a thin, flexible fringe of tissue around the vaginal opening. Some people are born with very little of it, some have more. It can wear away through sports, tampon use, or just moving around. The idea that you can "check" it to prove anything is medically illiterate.

Taking Action: How to Actually Monitor Your Health

Understanding female anatomy with organs isn't just for passing a biology quiz. It’s about knowing when something is actually wrong.

✨ Don't miss: Understanding Female Body Parts With Diagram: What Your Doctor Might Not Have Explained

- Map your cycle: Use an app or a paper journal. Don’t just track the bleeding. Track the "egg white" cervical mucus (ovulation), track the mood swings, track the bloating.

- The "Mirror Test": Seriously. Grab a hand mirror. Look at yourself. Know what your external anatomy looks like so you can spot changes in skin color, texture, or new bumps.

- Pelvic Floor Check: See a specialist if you have "heaviness" in the pelvis or if you can't jump on a trampoline without worrying. Kegels aren't for everyone; sometimes your muscles are actually too tight (hypertonic) and you need to learn to relax them, not tighten them.

- Advocate in the Office: If you have excruciating period pain, don't let a doctor tell you "it's just part of being a woman." Endometriosis (where the lining grows outside the uterus) takes an average of 7 to 10 years to be diagnosed because women's pain is often dismissed.

Pay attention to your "normal." Your anatomy is a system of moving parts, and while it's resilient, it requires you to be the primary investigator. If something feels "off" in the pressure, the pain, or the discharge—it probably is. Trust your gut. It lives right next to all these organs, after all.

Explore your family history for things like fibroids or PCOS (Polycystic Ovary Syndrome), as these often have a genetic component. Keep a log of any persistent pelvic pain and bring it to your next gynecological exam. Use specific terms—mention the "fundus," the "cervix," or the "pelvic floor"—to show your provider you understand your body and expect a high level of care.