It is kind of wild that we live in an era of space tourism and lab-grown meat, yet most adults would struggle to accurately label a basic female body parts with diagram. Seriously. Think about it. We spend years in school learning about the mitochondria being the "powerhouse of the cell," but when it came to the actual mechanics of the female reproductive system, most of us got a thirty-minute awkward video in a sweaty gym and a grainy handout. This lack of clarity isn't just a "fun fact" problem; it's a health literacy crisis.

When you don't know the territory, you can't be an effective advocate for your own body.

Most people use "vagina" as a catch-all term for everything down there. It's not. That’s like calling your entire face an "eye." Understanding the distinction between the vulva and the internal organs is the first step toward better sexual health, easier medical visits, and honestly, just feeling more empowered.

The Anatomy You Can Actually See: The Vulva

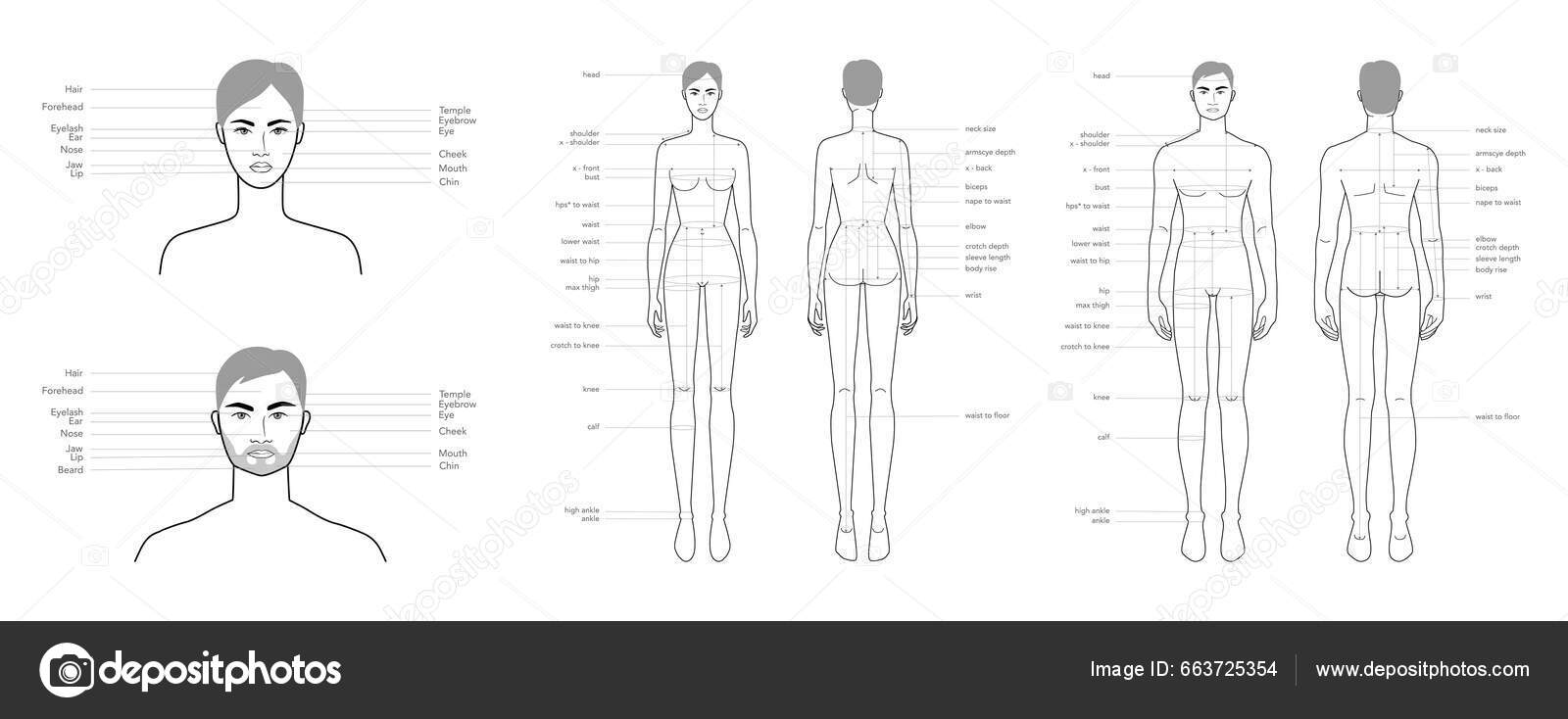

Let’s start outside. The vulva is the collective name for all the external parts. People get this wrong constantly. Even some medical textbooks historically glossed over the complexity here.

First up is the mons pubis. This is that fleshy, fatty tissue over the pubic bone. Its main job? Protection. It acts like a cushion during intercourse and protects the underlying bone. Then you have the labia majora and labia minora. These are the "lips." The majora are the outer ones, usually covered in hair, while the minora are thinner, more sensitive folds of skin inside. There is a massive range of "normal" here. Some are long, some are short, some are asymmetrical.

In 2018, a study published in BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology looked at over 650 women and found that the variation in labial size is huge—sometimes several centimeters of difference. This is important because the "perfect" look pushed by media is mostly a myth.

✨ Don't miss: The Back Support Seat Cushion for Office Chair: Why Your Spine Still Aches

The Clitoris: More Than a Button

Most diagrams show the clitoris as a tiny pea-sized nub at the top. That is barely the tip of the iceberg. Literally.

The clitoris is an expansive organ. Most of it is internal. It has "legs" (crura) and "bulbs" that wrap around the vaginal opening. It is the only human organ dedicated entirely to pleasure, containing roughly 8,000 to 10,000 nerve endings. For context, the glans of a penis only has about half that. When you look at a modern female body parts with diagram that includes the internal clitoral structure, it looks more like a wishbone or a butterfly than a dot.

Moving Inside: The Vaginal Canal and Beyond

Once you move past the vestibule (the area inside the labia minora), you hit the vaginal opening. The vagina itself is a muscular, elastic tube. It’s about 3 to 6 inches long on average, though it can stretch significantly during arousal or childbirth.

It’s self-cleaning. Please stop douching.

The vagina maintains a specific pH balance—usually between 3.8 and 4.5—thanks to Lactobacillus bacteria. When you introduce soaps or "scented" products, you kill the good guys and invite yeast infections or bacterial vaginosis (BV). Dr. Jen Gunter, an OB-GYN and author of The Vagina Bible, has spent years debunking the idea that the vagina needs "refreshing." It doesn't.

🔗 Read more: Supplements Bad for Liver: Why Your Health Kick Might Be Backfiring

The Cervix: The Gatekeeper

At the very end of the vaginal canal sits the cervix. If you’ve ever felt it with a finger, it feels a bit like the tip of your nose—firm but slightly givey. It’s the lower part of the uterus.

The cervix is a fascinating bit of engineering. It produces different types of mucus throughout the menstrual cycle to either block sperm or help it swim through. During labor, it thins out (effaces) and dilates to 10 centimeters. That’s roughly the size of a bagel.

The Powerhouse: Uterus and Ovaries

The uterus, or womb, is where the magic (or the monthly annoyance) happens. It’s a pear-shaped organ that is surprisingly small when not pregnant—about the size of your fist. It has three layers:

- Perimetrium: The outer protective layer.

- Myometrium: The thick muscle layer that causes cramps and pushes babies out.

- Endometrium: The inner lining that builds up and sheds every month.

Then we have the Fallopian tubes. These aren't actually "attached" to the ovaries in the way most people think. They have these finger-like fringes called fimbriae that hover over the ovaries. When an egg is released, the fimbriae sweep it up into the tube like a vacuum.

The Ovaries: Hormone Factories

The ovaries are about the size of large almonds. They have two main jobs: storing eggs and pumping out hormones like estrogen and progesterone. You’re born with all the eggs you’ll ever have—about 1 to 2 million—but by the time you hit puberty, only about 300,000 remain.

💡 You might also like: Sudafed PE and the Brand Name for Phenylephrine: Why the Name Matters More Than Ever

Why This Matters: The Medical Gap

Historically, female anatomy was studied less than male anatomy. It wasn't until 1998 that Helen O'Connell, an Australian urologist, used MRI technology to fully map the internal structure of the clitoris. That’s late. Very late.

This "data gap" means that many women grow up not knowing how their own bodies function. For example, many people don't realize the urethra (where you pee) is entirely separate from the vagina. If you’re trying to use a tampon or a menstrual cup and you’re aiming for the wrong hole, it’s going to be a bad time.

Understanding your anatomy helps you spot when things are wrong. If you know what your "normal" looks like, you’ll notice a change in the color of your labia, a new bump, or an unusual discharge earlier. This leads to faster diagnosis for things like PCOS, endometriosis, or even vulvar cancer.

Actionable Next Steps for Body Literacy

It's one thing to read about it; it's another to know your own specific map. Anatomy is universal, but your body is individual.

- Perform a Self-Exam: Take a hand mirror and find a private, comfortable spot. Identify the parts discussed: the mons, the labia, the clitoral hood, and the vaginal opening. Knowing your baseline is essential for noticing changes.

- Track Your Cervical Mucus: This isn't just for people trying to get pregnant. Observing how your discharge changes from "egg white" to "creamy" to "dry" tells you exactly where you are in your hormonal cycle.

- Update Your Vocabulary: Start using the word "vulva" when referring to external parts. It sounds pedantic, but accuracy helps you communicate better with healthcare providers. If you tell a doctor your "vagina" hurts, but the pain is actually on your labia, it can lead to a misdiagnosis.

- Consult Reliable Diagrams: Look for "3D clitoral anatomy" or "anatomical vulva maps" from reputable sources like the Mayo Clinic or Planned Parenthood. Most textbook illustrations from twenty years ago are outdated and omit the full internal structures.

- Schedule a Pelvic Exam: If you haven't had a check-up in a while, use this new knowledge to ask your doctor specific questions. Ask them to point out your cervix during the exam if you're curious; most providers are happy to explain what they are seeing.

Owning the language of your own body removes the shame and replace it with clinical, practical confidence.