Ever flicked a light switch and wondered why the bulb glows instantly? You’re not alone. Most people imagine a tiny spark racing at light speed from the wall to the lamp. That's not really how it works. Honestly, the reality of electric current is way weirder, a bit slower, and infinitely more interesting than the "water in a pipe" analogy we all learned in middle school.

Think about a copper wire. It’s packed with electrons. When you flip that switch, you aren’t sending a brand new electron from the power plant into your house. You're just nudging the ones that are already sitting there. It’s like a garden hose already full of water; as soon as you turn the tap, water comes out the other end because the pressure pushes the whole column at once.

What is the Electric Current Anyway?

At its most basic level, we’re talking about the flow of electric charge. In most of our daily lives—like charging your phone or running a blender—that charge is carried by electrons. But it’s not always electrons. If you’re looking at a battery’s internal chemistry or the way your nerves send signals to your brain, you’re dealing with ions. Positive or negative, if charge is moving, you’ve got a current.

Physicists define it as the rate of flow. We measure it in Amperes, or "Amps" for short. One Ampere is a staggering amount of data: roughly $6.24 \times 10^{18}$ electrons passing a single point every second. That’s a lot of zeros. If you tried to count those electrons one by one, you’d be at it for several lifetimes.

The Great Misconception: Speed

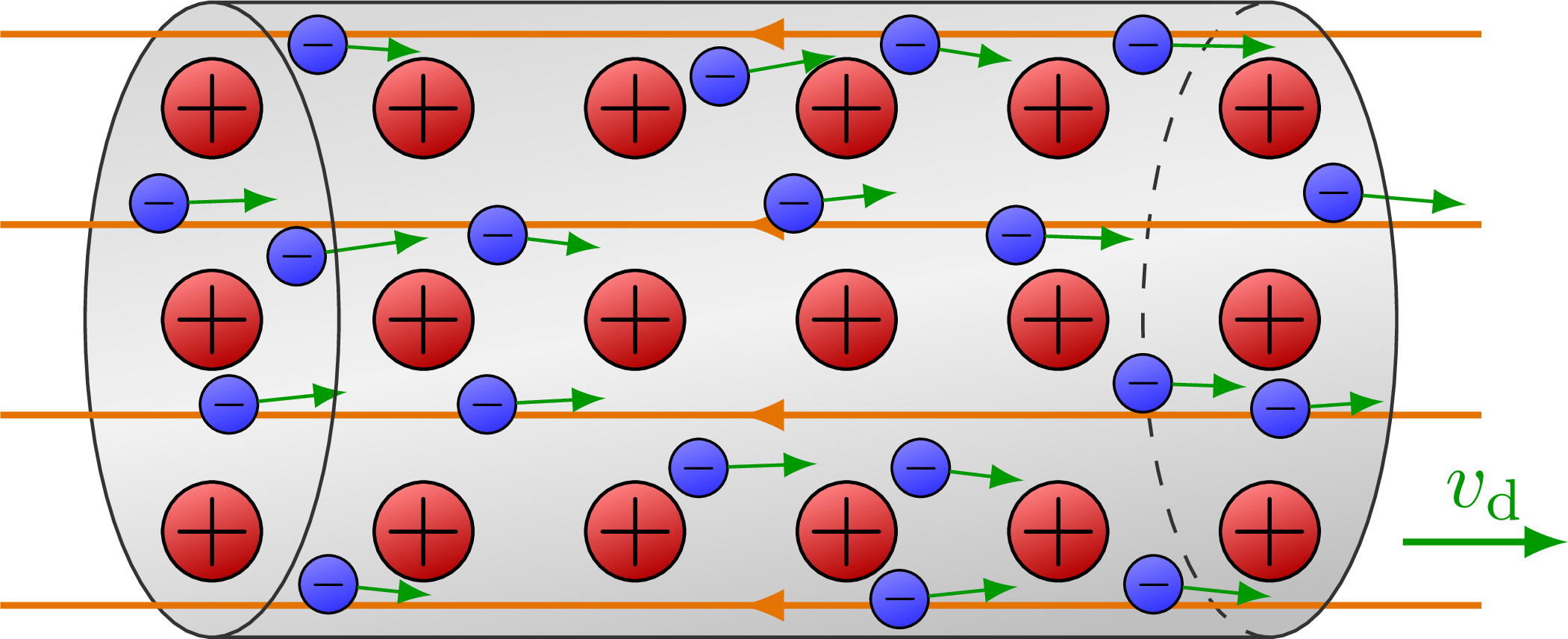

Here is where it gets trippy. Electrons themselves are actually incredibly slow. This is called "drift velocity." If you have a typical copper wire in your wall, the individual electrons are crawling along at about a millimeter per second. A snail could literally outrun an electron.

So why does the light turn on instantly?

Because the energy—the electromagnetic field—travels at nearly the speed of light. It’s the difference between a wave moving through the ocean and the actual water molecules staying more or less in the same spot. The field tells all the electrons to move at once.

Why You Should Care About Amps vs. Volts

People get these confused constantly. Think of it this way:

- Voltage is the pressure. It’s the "push" behind the charge.

- Current (Amps) is the actual flow.

- Resistance (Ohms) is the friction trying to stop it.

If you have high voltage but no path for the current to flow, nothing happens. It’s a pressurized tank with the valve shut. But once you provide a path (a circuit), the current starts moving. This relationship is governed by Ohm’s Law: $I = V / R$.

Benjamin Franklin actually messed us up a bit here. Back in the day, he guessed that electricity flowed from positive to negative. We call this "conventional current," and it's still how almost all electrical diagrams are drawn today. Decades later, scientists realized that electrons—which are negatively charged—actually flow from the negative terminal to the positive one. We just stuck with Franklin’s version because changing every textbook in the world seemed like a massive headache.

AC vs. DC: The War of the Currents

You’ve probably heard of the band, but the actual history involves Thomas Edison and Nikola Tesla getting into a very public, very messy fight.

Direct Current (DC) is what you get from a battery. It flows in one direction, steady and predictable. It’s great for electronics. Your laptop runs on DC, which is why that "brick" on your charging cable exists—it converts the AC from your wall into DC.

Alternating Current (AC) is what the power grid uses. In the US, it switches direction 60 times per second (60 Hz). Why? Because it’s much easier to transform AC to very high voltages for long-distance travel. If we tried to power a city with low-voltage DC like Edison wanted, we’d need a power plant on every street corner because the energy loss over long wires would be too great.

The Danger Factor: It's the Amps that Kill

You’ve seen the "Danger: High Voltage" signs. But interestingly, voltage isn't what stops your heart—it’s the current. A static shock from a doorknob can be thousands of volts, but the amperage is so tiny it’s harmless.

On the flip side, even a small amount of current can be lethal if it passes through the chest.

- 1 milliamp (mA): Just a tingle.

- 10-20 mA: "Let-go" threshold. Your muscles contract so hard you literally can't let go of the wire.

- 100-200 mA: Ventricular fibrillation. This is the danger zone where the heart loses its rhythm.

This is why Ground Fault Circuit Interrupters (GFCIs)—those outlets with the "reset" buttons in your kitchen or bathroom—are so vital. They sense if the current is leaking somewhere it shouldn't be (like through you) and cut the power in milliseconds.

Real World Applications You Might Not Realize

Most of us think of light bulbs and toasters, but current is the backbone of the modern "smart" world.

✨ Don't miss: iPhone 15 Pro Battery: Why Your Mileage Varies So Much

In a transistor—the tiny switches inside your computer chip—the presence or absence of a tiny pulse of electric current represents a 1 or a 0. We’ve gotten so good at controlling these currents that we can fit billions of these switches on a piece of silicon the size of a fingernail.

Then there’s the medical side. Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS) units use small currents to scramble pain signals before they reach the brain. We are, essentially, bio-electrical machines. Your heart's "pacemaker" is a cluster of cells that generates an electric current to make the muscle contract. When that fails, we use a literal battery-powered pacemaker to do the job.

Why Resistance Changes Everything

Everything except superconductors has some level of resistance. When current fights through resistance, it generates heat.

Sometimes we want this. A space heater or a hair dryer is just a big coil of high-resistance wire (usually nichrome) that gets glowing hot when current passes through it. But in your phone or laptop, that heat is the enemy. It's wasted energy. This is why "efficiency" is such a buzzword in tech—we’re trying to find ways to move current without losing half of it as heat.

Getting Practical: What This Means for Your Gear

Understanding current helps you not fry your expensive electronics.

- Check the Amperage: If you use a charger that provides 1 Amp on a tablet that requires 2.1 Amps, it will charge painfully slowly, or not at all.

- Heat is the Warning: If a wire or a plug feels hot to the touch, you’ve got too much current for that specific gauge of wire. That’s a fire hazard.

- Daisy-Chaining Power Strips: Don't do it. Each strip adds resistance and increases the total current draw on the first outlet, which can lead to melting and electrical fires.

Moving Forward with Electrical Safety

If you're looking to dive deeper into how your home works or if you're planning a DIY project, the next step is to grab a basic digital multimeter. It’s a tool that lets you actually see the current and voltage in real-time. Learning to use one is like getting a pair of X-ray specs for your house.

Start by testing simple things, like the voltage left in a "dead" AA battery. You'll quickly see that most batteries labeled as dead still have a charge; they just don't have enough "pressure" to power the device.

Don't just take the grid for granted. Every time you charge your car or even just turn on a flashlight, you're participating in a complex dance of subatomic particles that humans only really figured out a couple of centuries ago.

Take a look at your home’s breaker box today. See which circuits are rated for 15 Amps and which are 20 Amps. Knowing the limits of your system is the first step toward being a more informed (and safer) homeowner.